For centuries people and communities have been on the move, whether it was a simple journey from the countryside to the nearest town in search of work, or across continents to the New World in search of a better life.

In England, the county of Norfolk was no exception to this phenomenon. The eastern county situated on the coastline experienced significant migration throughout the centuries ranging from the Romans, to the Vikings and in the latter half of the Middle Ages, the Dutch and Flemish.

Situated in East Anglia and bordered by Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Suffolk to the south, the Norfolk coastline itself sits nearby its continental neighbours across the water, the Netherlands.

In medieval times, the continent could be reached in a day of travelling as it took that long to sail to Amsterdam. Norfolk itself was a very rural area, with muddy marshland to navigate as well as dense forests. Some of the most urban areas in the county today consist of the towns of Great Yarmouth, King’s Lynn, Thetford and of course Norwich.

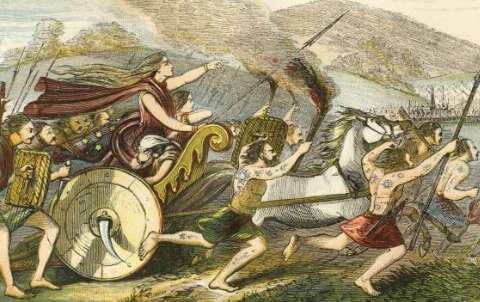

The history of the region is dominated by various groups throughout the centuries, most famously of course the Iceni tribe who were led by the iconic female warrior Boudica in 60 AD. The Brythonic tribe pre-dated the Romans and were not willing to accept the invasion by foreign powers without a fight.

Sadly, their bravery was not enough against the might of the Romans and soon enough Roman influence spread throughout the county, visible in its roads, ports and farming.

As a result of its geography Norfolk, on the east coast of England, was often vulnerable to attack from invasions from its continental neighbours. In a time of great expansion by the Vikings, hordes of fighters descended from Scandinavia.

In the fifth century, the Angles had gained control of the region, hence the origin of the name East Anglia with the people known as the ‘north folk’, preceding the name Norfolk.

In the years and centuries which followed the county, dominated by wetlands, began to create farmland which encouraged further settlement. Nourished by a developing agricultural industry, the migration to the area continued to rise throughout the Middle Ages.

In this time of expansion, more and more churches were built based on the prosperous industry of woollen production as well as farming. It was at this point that the burgeoning possibilities of trade saw Norwich spread its tentacles with trading networks spread across Europe including Spain, Scandinavia and the Low Countries.

Nevertheless, the county was hit hard by the scourge of the Black Death which had swept across the continent massacring populations and leaving areas sparse and desolate in its wake, Norfolk was no exception.

Nonetheless, the area began to grow again, mirroring many other communities which had been decimated by the plague. In the centuries that followed Norfolk re-established itself once more and by the late sixteenth century the urban centre of Norwich was continuing to grow and develop, despite the ongoing battles with disease.

Meanwhile, under the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, an important decision was made in order to bring life back into the woollen industry in the region. In 1565, the Queen invited Dutch weavers to settle in Norfolk in a proclamation in which she referred to them as “Strangers” and as “England’s most ancient and familiar neighbours”.

The group would be known as “Elizabethan Strangers” and quickly settled into life in Norfolk bringing with them skills, talents and trades. The group itself consisted of Protestant refugees from the Spanish Netherlands who were invited to England in order to boost the textile industry with their knowledge and craft.

The Catholic Low Countries political asylum seekers mainly settled in Norwich, with the initial influx arriving in 1565 and with several other groups following in the subsequent years. These “strangers” quickly formed a substantial part of the Norfolk community and in Norwich specifically, made up around one third of the city’s population.

The exiled community which settled in Norwich came from locations such as Ypres and the “western quarter” of the Southern Netherlands where the roots of the Dutch Revolt were beginning to germinate.

As the immigrants fled for reasons relating to religious persecution, around thirty households of master weavers made the journey to England in search of a better life.

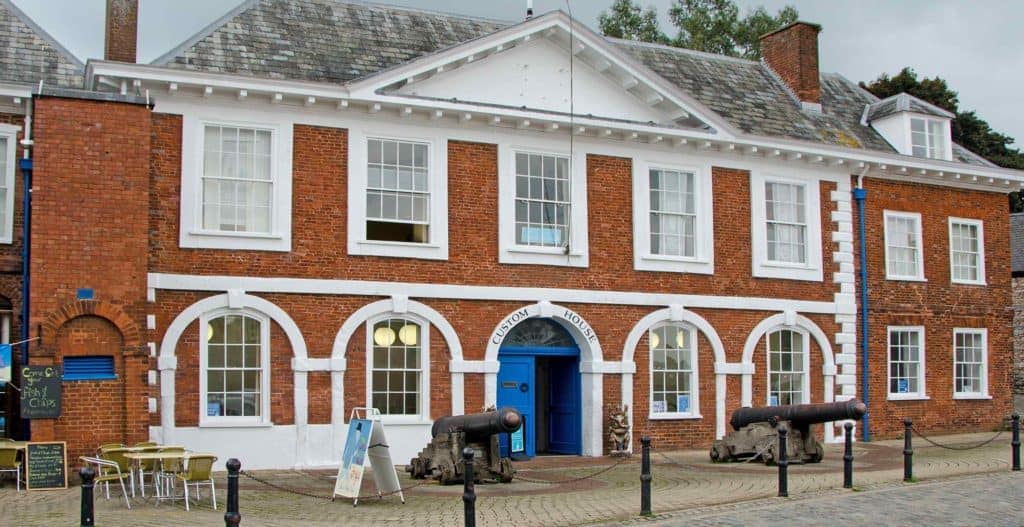

The prospect of safety in which to live and practice your craft enticed a substantial community of Flemish and Walloon to Norwich. In the beginning, upon their arrival, the merchant’s house would have been their first port of call. Today, it is a museum, still known by the name “Strangers’ Hall”.

The arrival of new people into the community did not appear to cause any friction within the local community, on the contrary in fact. Many people, particularly in the woollen trade and fellow businessmen were keen to learn skills from their continental partners. The group’s entrance into Norwich society was thus welcomed and they soon managed to ingratiate themselves with the locals.

The introduction of the Dutch weavers sparked an important turning point for the city of Norwich which immediately felt the impact of boosted trade with Europe. Moreover, the influence of the new community members also began to be felt in other areas of life besides business.

A new social conscience began to emerge from the people of Norwich who witnessed the plight of the Protestant “strangers” fleeing persecution from the Catholics. This subsequently sparked a growing awareness in the city of the social and religious injustices being committed. It should come as no surprise then, that in response to the increased awareness, Norwich became the first city of its kind to introduce compulsory payments for poor relief, initiating the basic principles of the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1597. Thus demonstrating the wide-ranging impact of the immigrants on the community spirit for reform, politics and social justice.

In addition to increased social engagement, the Dutch refugees brought with them a range of trades, skills and knowledge, including printing, which was introduced by a man called Anthony de Solempne.

Norfolk received a huge boost in its wool trade, infrastructure, culture and architecture including distinctive gable ends which can be found across the county, inspired by Dutch styles.

Dutch-style roof on house on Green Man Lane, Kirstead Green, Norfolk.

In terms of infrastructure, the region received a major boost from engineering projects carried out by Dutch engineer Joas Johnson who was responsible for the piers at Great Yarmouth. His constructions were destined to last several centuries until 1962 when “The Old Dutch Pier” was eventually replaced.

By the 1650’s, major projects involving sluices were used to control the water and connect communities which had always been forced to navigate the marshland topography.

Moreover, with the great boost to infrastructure, engineering and architecture, the new Dutch residents also brought with them a rather unusual surprise, pet canaries. These attractive yellow birds eventually became synonymous with the city of Norwich and today serve as the emblem for Norwich City Football Club who carry the nickname of “The Canaries”.

By the end of sixteenth century, there were around 4000 refugees who fled persecution and set up a new life in Norfolk. As they began to settle in their newly adopted home, they managed to transform and revive the area, bringing with them skills, prosperity and knowledge.

The county of Norfolk, blessed with rural beauty and potential became the meeting place for various communities seeking to make a life for themselves. Over the centuries, the region had been conquered, settled, decimated, rebuilt, developed and expanded.

Whilst the area was well-known for its textile industry, it was the densely woven fabric of a community which earned the region its greatest fortunes.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: August 27th, 2021.