In the late 1500s, European explorers started sailing east for trading purposes. The Spanish and the Portugese were originally dominant on these new sailing routes, but after the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588 the British and Dutch were able to take more of an active role in trade with the East Indies. The Dutch initially took a lead in this, focusing mainly on spices and in particular the trade of peppercorns.

Concerned that the English were falling behind to the Dutch on these new trading routes, on the 31st December 1600 Queen Elizabeth I granted over 200 English merchants the right to trade in the East Indies. One of these groups of merchants called themselves Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies, later to become simply The East India Company.

As the name suggests, the Company’s humble origins was as a small group of investors and businessmen looking to capitalise on these new trading opportunities. Their first expedition left for Asia in 1601 with four ships commanded by James Lancaster (pictured to the right). The expedition returned two years later with a cargo of pepper weighing almost 500 tons! James Lancaster was duly knighted for his service.

As the name suggests, the Company’s humble origins was as a small group of investors and businessmen looking to capitalise on these new trading opportunities. Their first expedition left for Asia in 1601 with four ships commanded by James Lancaster (pictured to the right). The expedition returned two years later with a cargo of pepper weighing almost 500 tons! James Lancaster was duly knighted for his service.

Although these initial voyages turned out to be extremely profitable for the shareholders, increased competition in the mid-1600s made trading much more difficult. Wars, pirates and lower profit margins forced the Company to grow into new markets where competition was less fierce. It was during this time that the Company also decided that it could not compete with the more powerful Dutch East India Company in the trading of spices, so instead turned its attention to cotton and silk from India.

This strategy appeared to pay off, as by the 1700s the Company had grown so large that it had come to dominate the global textile trade, and had even amassed its own army in order to protect its interests. Most of the forces were based at the three main ‘stations’ in India, at Madras, Bombay and Bengal.

Although the forces of the East India Company were at first only concerned with protecting the direct interests of the Company, this was to change with the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Faced with a local uprising led by Siraj ud-Daula (with some French assistance!), the Company’s army led by Robert Clive quickly defeated the insurgents. However, this was to be a turning point for the Company and the following years saw it take full administrative powers over its territories, including the right to tax anyone living within its boundaries.

Although the 1600s and early 1700s saw the East India Company primarily focused on the trade of textiles, by the mid 18th century the Company’s trading patterns began to change. The reasons for this were two-fold.

Firstly, the industrial revolution had changed the way that the Company dealt with the textiles trade. Prior to this, highly skilled weavers were employed in India to make cottons and silks by hand. These light, colourful and easy to wear garments were popular amongst the fashionistas and upper classes of Britain.

By the time of the Industrial Revolution, Britain had started producing these garments in its own factories, dramatically lowering prices (due to mass production) and bringing the fashions into the reach of the middle classes.

The second reason for this change in trading patterns was the growing desire in Europe for Chinese tea. This was a potentially massive market for the Company, but was held back by the fact that the Chinese only traded their tea for silver. Unfortunately Britain was on the gold standard at the time, and had to import silver from continental Europe, making the whole tea trade financially unviable.

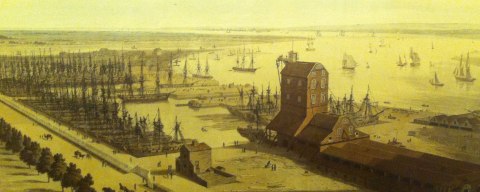

The East India Company didn’t actually own many of the ships in its fleet. It rented them from private companies, many of which were based at Blackwall in East London. The picture above is of Mr Perry’s Yard, which also built ships for the British navy.

So how did the East India Company make its fortune in Chinese tea?

In short, through illegal drugs! The Company started encouraging opium production in its Indian territories, which it then gave to private merchants (heavily taxed, of course) to be sold to China. The tax revenues from this funded much of the Company’s profitable tea business.

Unfortunately this broke Chinese law, although it was tolerated by the authorities for a good 50 years until the trade balance fell to such a point that the Chinese could not afford to let it continue. This came to a head in 1839 when the Chinese demanded that all opium stock be handed over to its government for destruction. This ultimately led to the Opium Wars.

“…there is a class of evil foreigner that makes opium and brings it for sale, tempting fools to destroy themselves, merely in order to reap a profit.”

Commmissioner Lin Zexu, 1839

The Nemesis, an East India Company warship, destroying Chinese vessels during the First Opium War

At the same time as the Opium Wars, the Company started witnessing an increasing amount of rebellion and insurgence from its Indian territories. There were many reasons for this insurgency, and the Company’s rapid expansion through the sub-continent during the 18th and early 19th century had not helped matters.

The rebels, many of whom were the Indian troops within the Company’s army (which at this time was over 200,000 men strong, with around 80% of the force made up of Indian recruits) caught their employers off guard and succeeded in killing many British soldiers, civilians and Indians loyal to the Company. In retaliation for this uprising, the Company killed thousands of Indians, both rebel combatants as well as a large number of civilians perceived to be sympathetic to the uprising. This was the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

“It was literally murder… I have seen many bloody and awful sights lately but such a one as I witnessed yesterday I pray I never see again. The women were all spared but their screams on seeing their husbands and sons butchered, were most painful… Heaven knows I feel no pity, but when some old grey bearded man is brought and shot before your very eyes, hard must be that man’s heart I think who can look on with indifference…”

Edward Vibart, 19 year old British officer

The Indian Rebellion was to be the end of the East India Company. In the wake of this bloody uprising, the British government effectively abolished the Company in 1858. All of its administrative and taxing powers, along with its possessions and armed forces, were taken over by the Crown. This was the start of the British Raj, a period of direct British colonial rule over India which continued until independence in 1947.

It accomplished a work such as in the whole history of the human race no other Company ever attempted and as such, is ever likely to attempt in the years to come.

The Times, 2nd January 1874

Published: 26th March 2015