One of the most tumultuous periods of English history took place between 1642 and 1651, resulting in the execution of King Charles I and the temporary abolition of the monarchy.

The English Civil War divided the country, with people and families split between their values and opinions on power, human suffrage and political freedom.

Emerging out of the violence, turbulence and chaos were the Levellers, a political movement which preached ideas of equality, religious tolerance, suffrage and sovereignty.

The name itself was a derisory term for rural rebels and although members would have preferred to have been referred to as “agitators”, the name “levellers” stuck.

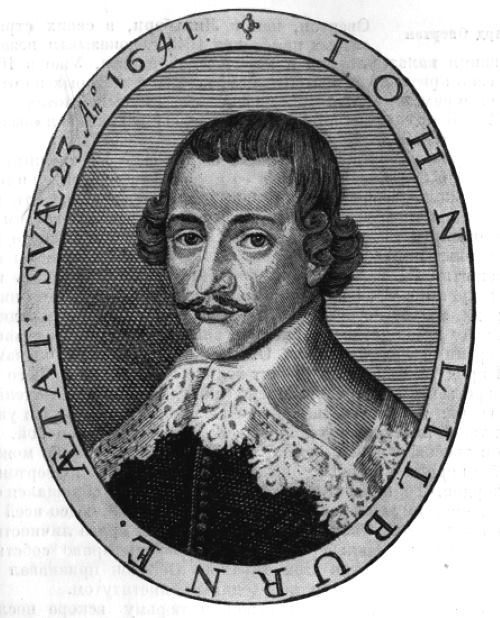

As an emerging political movement, particularly important figures in the group included Richard Overton, John Lilburne and William Walwyn, figures who would end up imprisoned for their views and actions.

In July 1645, Lilburne found himself incarcerated for accusing MPs of living luxuriously whilst the army fought for their supposed causes.

The Levellers arguments soon gained traction, particularly with the discontented members of the army and the English Civil War fast became a breeding ground for this group to emerge.

The Levellers gained most recognition after the first period of fighting in 1646, appealing to those who had been ignored, unappreciated and been suffering in silence.

In many ways, the Levellers embodied a populist movement and exercised further control and influence through a well-thought out propaganda mechanism which involved pamphlets, petitions and speeches, all of which connected the group with the general public and conveyed their message.

Together with the infamous Thomas Cromwell they campaigned for a new political landscape which would emphasise freedom and inclusiveness, principles which would many years later be adopted by the revolutionaries of France and later America.

Whilst Cromwell and the Levellers were initially on the same page with regards to their principles and goals, they soon fell out over method and approach and began to work against one another.

In the summer of 1647, the group began to formalise their plans which involved a sweeping democratising process for both England and Wales which would have revolutionised and contested the accepted authority of parliament.

In doing so, they quickly lost the necessary backing they would have required in order to bring about such radical changes. Without the support of people within the very institution they were defying, their goals would be difficult to achieve.

In June 1647, growing support for the Levellers came from the army who had expressed discontent on a range of issues, which the political movement would use to gain their support. This included monetary problems with pay arrears and a possible new campaign to be launched in Ireland.

Meanwhile, the Levellers delivered their key list of demands to Parliament, calling for sweeping changes and radical reform. Some of these changes included the dissolution of the Long Parliament with a new assembly elected in its place. Another key proponent in the Levellers philosophy included extending suffrage so that a wider group would elect the new assembly. It was also made clear that if none of these demands could be met, then Parliament would be dissolved by the force of the army if necessary.

Whilst the Levellers had believed they had done enough to secure the support of the army, they had in fact miscalculated. In fact, the result of such a threat led the Grandees of the army to come out in support of the Long Parliament, a loyalty which was exhibited by a demonstration in London.

The fight however was far from over; division still existed and the army was far from being won over by either side.

In October of the same year, the influential soldier and politician Major John Wildman published a document which contained the demands from the army, based on well-known grievances and stated how revolutionary political action could bring about these desired changes.

The document was called, “The Case of the Army Truly Stated” and contained within it many radical ideas such as the restriction of the power of MPs, elections every two years, the guarantee of certain political rights such as religious tolerance and the emphasis that power should ultimately lay in the hands of people, an early indication of universal suffrage (although the concept was not fully formed or stated in these terms yet).

This revolutionary document was eventually edited and the publication became known by the slightly catchier name of, the “Agreement of the People”. The message of the document was simple: power to the people!

The political movement advocated such an idea based on its Christian origins and the belief that everyone has the ability to use reasoning to make informed decisions for themselves.

Rather unsurprisingly, the Long Parliament were less than receptive to such changes, nonetheless a consensus of opinion concluded that a debate should take place in which to discuss the Levellers’ key demands.

The support for the Levellers within the New Model Army was quite strong. Formed in 1645, the army included veterans and other conscripts who held deeply religious beliefs. In this respect, they differed greatly from the regular army and their dissenting support for the Levellers created concern for the likes of Cromwell and his men.

The airing of these grievances took place in the late autumn at Putney Church where the two main speakers stated their claims. On the side of Parliament was Henry Ireton, an English general, who also happened to be the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. Well-known for his dislike of extremism, he argued for a more moderate approach as anything more radical, such as suggested by the Levellers, was destined to have disastrous effects on society.

On the other side of the argument, “the Agitators” spoke on behalf of the Levellers, representing the more radical opinions within the army.

Whether or not these two groups could find any common ground remained to be seen. On the issue of franchise, the Levellers believed in universal male suffrage whilst Ireton made the case for suffrage based on ownership and property, which would have excluded large swathes of working men who were guilty only of being poor.

The Putney Debates raged on until November, when indecision and lack of agreement began to concern Cromwell who anticipated the army splitting over such issues.

The Agitators wanted to ascertain what would be done about the king. This lead to further discussions which were interrupted on 11th November when King Charles I escaped from his captivity at Hampton Court Palace, bringing the debate to an abrupt end.

The New Model Army now had an impending threat to deal with, fearing that Charles I might succeed in rallying forces if he made it to France.

Whilst the debate was abandoned for more immediate concerns, the General Council presented a new manifesto which included a clause which maintained that the army would declare loyalty both to the Council and Lord Fairfax, the army general and Parliamentary Commander-in-Chief.

With such events unfolding, Parliament and its supporters in the army were able to seize their chance to secure discipline in the ranks. Both Fairfax and Cromwell wanted to suppress the dissenting voices in the army and imposed the Heads of Proposals as an Army Manifesto which had to be signed by each officer.

Rather than the proposed Leveller’s “Agreement of the People”, the new army manifesto secured loyalty to Fairfax by ensuring that the back payments many officers had been owed would be honoured.

Nevertheless, a small mutiny did occur on 15th November known as the Corkbush Field Mutiny, when a handful of soldiers refused to sign, rebelled and were arrested, whilst the ringleader, Private Richard Arnold was shot.

It was at this moment that the Levellers really lost their sway with the army whilst Cromwell and his supporters were able to rally the troops in order to begin a second round of fighting.

The Levellers had been outmanoeuvred by Cromwell and their opposition; their ideas had proved too radical and the incentives were simply not enough to entice the army.

A new revised edition of the “Agreement of the People” was produced but sadly amounted to nothing, put to one side and ignored by Parliament.

However support for the Levellers was not completely dispelled, it was simply silenced, with some small pockets of subversion emerging, especially after the execution of Charles I in January 1649.

In April, only three months after the king’s death, the Bishopgate Mutiny took place, leading to a certain Robert Lockyer, a supporter of the Levellers, being executed by firing squad.

After the Grandees of the army banned petitions by soldiers to Parliament, many of the Levellers still serving in the army were outraged, however they were treated with draconian force.

In May 1649 around 400 troops, all of whom adhered to the ideas of the Levellers and led by Captain William Thompson, gathered in Banbury and marched towards Salisbury. Whilst a mediator had been sent to deal with the matter, on 13th May Cromwell chose to launch a surprise attack leading to several of the Leveller mutineers being killed in the process. This became known as the Banbury Mutiny.

This was the final blow to the Leveller movement and its power base in the New Model Army; they had been crushed. Cromwell was now the main orchestrator for the rest of the English Civil War whilst the Levellers’ attempts fell by the wayside, lost to the shadows of history.

*Since 1975, on the Saturday nearest to 17th May the town of Burford has commemorated Levellers’ Day in memory of the mutineers executed there.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.