Most of the articles featured on Historic UK have a limited word count in an attempt to capture and retain the readers’ interest and imagination. The following article concerning the Vanished Battalion extends to many times the normal length for reasons which will become obvious on reading.

The Background

The men of E Company had grown up together, playing cricket for the same village team, chasing the same girls and drinking in the same pubs and inns. And now, as members of the 5th Territorial Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment, they were about to go to war together.

It was the hot August of 1914 and groups of friends or ‘buddies’ across Britain, team-mates and work colleagues eagerly enlisted to fight the Bosch.

But what the soldiers of E Company had in common was something rather unusual: they all belonged to the staff of the Royal Estate at Sandringham.

The company had been formed in 1908 at the personal request of their employer, King Edward VII. He asked Frank Beck, his land agent to undertake the task. This he did, recruiting more than 100 part-time soldiers or territorials.

As was the custom in the territorial battalions of the day, military rank was dictated by social class. Members of the local gentry like Frank Beck and his two nephews became the officers. The estate’s foremen, butlers, head gamekeepers and head gardeners were the NCOs. The farm labourers, grooms and household servants made up the rank and file.

What happened to the Sandringhams during the disastrous Dardanelles campaign in the middle of their very first battle, on the afternoon of August 12, 1915? One minute the men, led by their commanding officer, Sir Horace Proctor-Beauchamp, were charging bravely against the Turkish enemy. The next they had disappeared. Their bodies were never found. There were no survivors. They did not turn up as prisoners of war.

They simply vanished.

General Sir Ian Hamilton, the British Commander-in-Chief in Gallipoli, appeared as puzzled as everyone else. He reported ‘there happened a very mysterious thing’. Explaining that during the attack, the Norfolks had drawn somewhat ahead of the rest of the British line. He went on ‘The fighting grew hotter, and the ground became more wooded and broken.’ But Colonel Beauchamp with 16 officers and 250 men, ‘still kept pushing on, driving the enemy before him.’

‘Among these ardent souls was part of a fine company enlisted from the King’s Sandringham estates. Nothing more was ever seen or heard of any of them. They charged into the forest and were lost to sight and sound. Not one of them ever came back.’ Their families had nothing to go on but rumours and a vague official telegram stating that their loved ones had been ‘reported missing’.

‘Among these ardent souls was part of a fine company enlisted from the King’s Sandringham estates. Nothing more was ever seen or heard of any of them. They charged into the forest and were lost to sight and sound. Not one of them ever came back.’ Their families had nothing to go on but rumours and a vague official telegram stating that their loved ones had been ‘reported missing’.

King George V could gain no further information other than that the Sandringhams had conducted themselves with ‘ardour and dash’.

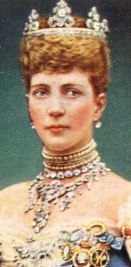

Queen Alexandra made inquiries via the American ambassador in Constantinople to discover whether any of the missing men might be in Turkish prisoner-of-war camps. Grieving families contacted the Red Cross and placed messages in the papers, hoping for news of their sons and husbands from returning comrades. But all to no avail.

So what really happened to men of Sandringham?

The Events…

Along with thousands of other troops, the 5th Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment had set sail from Liverpool on July 30, 1915, aboard the luxury liner Aquitania.

At 54, Captain Beck need not have led his men to war. But despite his age, he was determined to do so.

‘I formed them,’ he said bravely, ‘How could I leave them now? The lads will expect me to go with them; besides I promised their wives and children I would look after them’.

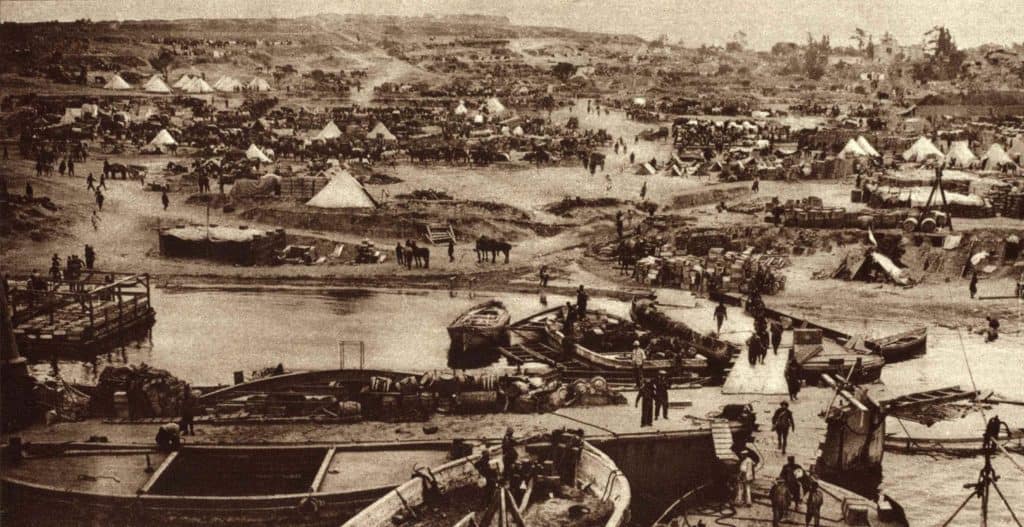

The battalion landed at Suvla Bay on August 10, in the thick of the fighting, and was immediately ordered inland.

Officers and men were being continually shot down, not only by rifle fire from the enemy in front of them, but by snipers.

The climate was broiling by day and freezing at night. Men were already suffering from dysentery and from the side-effects of inoculations and seasick tablets administered during the voyage. There was a desperate lack of water – two pints were supposed to last each man three days.

Then, on August 12, just two days after they had arrived in this arid, hostile land, the 5th Battalion was told it was to attack that afternoon.

The orders were confused. Some thought the plan was to clear away the enemy’s forward positions in preparation for the main British assault. Others believed their target was the village of Anafarta Saga on the ridge ahead of them.

The officers were handed maps, which they soon discovered did not even show the area they were supposed to be attacking.

Having been in the baking sun all day the inexperienced troops were thirsty and scared – and now they were to launch a major assault on a well-armed enemy in broad daylight and with little cover.

Only Private George Carr, a 14-year-old Norfolk lad, was to survive the bloodshed of that afternoon. Exhausted by the battle, he was saved by a stretcher-bearer called Herbert Saul, a pacifist who refused to carry a rifle on principle.

At 4.15-pm whistles blew and the Norfolks began to advance, led by Colonel Beauchamp, waving his cane and shouting: ‘On the Norfolks, on.’ Captain Beck was at the head of the Sandringhams.

Even though they were still a mile-and-a-half from the Turkish positions, the order to fix bayonets and to advance at the double was given. The slaughter began immediately as the Turkish artillery trained in on the advancing British soldiers. By the time the Norfolks reached the enemy lines they were already exhausted.

A desperate battle ensued, officers and men being cut down all around by snipers hidden in the trees. Everywhere officers and men of the battalion were dying. A shell landed close to Frank Beck. He was last seen sitting under a tree with his head on one side, either dead or simply too tired to continue.

In the midst of the bloodshed, Colonel Beauchamp continued to advance through a wood towards the Turks’ main positions, leading a band of 16 officers and 250 men. Among them were the Sandringhams.

Eventually, the Colonel was spotted, standing with another officer in a farm on the far side of the wood. ‘Now boys,’ he shouted, ‘ we’ve got the village. Let’s hold it.’

That was the last anyone saw or heard of Beauchamp, or any of his men, including the Sandringhams. They had all disappeared, amid the smoke and flying bullets, never to be seen again.

In 1918 when the war had ended, the War Graves Commission searched the Gallipoli battlefields. Of the 36,000 Commonwealth servicemen who died in the campaign, 13,000 rested in unidentified graves, another 14,000 bodies were simply never found.

During one of these searches a Norfolks regimental cap badge was found buried in the sand along with the corpses of a number of soldiers.

During one of these searches a Norfolks regimental cap badge was found buried in the sand along with the corpses of a number of soldiers.

The find was reported to the Rev Charles Pierre-Point Edwards, MC, who was in Gallipoli on a War Office mission to find out what had happened to the 5th Norfolks. It was likely that he had been sent there by Queen Alexandra.

Edwards’ examination of the area where the badge had been found uncovered the remains of 180 bodies; 122 of them were identifiable from their shoulder flashes as men of the 5th Norfolks.

The bodies had been found scattered over an area of one square mile, to the rear of the Turkish front line ‘lying most thickly round the ruins of a small farm’. This, Edwards concluded, was probably the farm at which Colonel Beauchamp had last been seen.

The surrounding area was wooded, the only area in the Suvla vicinity that matched with General Hamilton’s description of a forest.

Four years later came news from Turkey of a gold fob-watch, looted from the body of a British officer in Gallipoli. It was Frank Beck’s. The watch was later presented to Margeretta Beck, Frank’s daughter, on her wedding day.

And so it is here that the story of the Vanished Battalion might have ended.

The Mystery…

Many years later, in April 1965, at the 50th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings, a former New Zealand sapper called Frederick Reichardt issued an extraordinary testimony.

Supported by three other veterans, Reichardt claimed to have witnessed the supernatural disappearance of the 5th Norfolks in August 1915.

According to Reichardt, on the afternoon in question he and his comrades had watched a formation of ‘six or eight’ loaf-shaped clouds hovering over the area where the Norfolks were pressing home their attack.

Into one of these low lying clouds marched the advancing battalion. An hour or so later, the cloud ‘very unobtrusively’ rose and joined the other clouds overhead and sailed off, leaving no trace of the soldiers behind them.

This strange story first appeared in a New Zealand publication.

Despite its unreliable provenance and inconsistencies (Reichardt got the wrong date, the wrong battalion and the wrong location), this version of events captured popular imagination at that time.

More recent and detailed research for a BBC television documentary in 1991 called “All the King’s Men.” suggested that Reichardt’s story of the battalion-lifting cloud may have been a little confused. More significantly the BBC research unearthed two new important items of evidence.

More recent and detailed research for a BBC television documentary in 1991 called “All the King’s Men.” suggested that Reichardt’s story of the battalion-lifting cloud may have been a little confused. More significantly the BBC research unearthed two new important items of evidence.

The first piece of new evidence was an account of a conversation with the Rev Pierre-Point Edwards some years after the war, which revealed an extraordinary detail he omitted from his official report about the fate of the 5th Norfolks – namely, that every one of the bodies he found had been shot in the head.

It was known that the Turks did not like taking prisoners. This was confirmed by the second piece of evidence, which told the story of Arthur Webber, who fought with the Yarmouth Company of the 5th Norfolks during the battle of August 12, 1915.

According to his sister in-law, Arthur was shot in the face. As he lay injured on the ground, he heard the Turkish soldiers shooting and bayoneting the wounded and the prisoners around him. Only the intervention of a German officer saved his life. His comrades were all executed on the spot.

Arthur Webber died in 1969, aged 86, still with the Turkish sniper’s bullet in his head.

Can the true fate of the 5th Battalion now be more fully explained?

In that after their bold dash through the wood on the 12th of August…

Colonel Beauchamp and the Sandringhams were overwhelmed by their Turkish enemies…

They were either captured or they surrendered…

The Turks took no prisoners…

So they were butchered…and buried.

Is this what became of the Vanished Battalion?

Update: Steve Smith, author of ‘And They Loved Not Their Lives Unto Death: The History of Worstead and Westwick’s War Memorial and War Dead’, has written a guest post for Historic UK which may shed some light on the fate of the Vanished Battalion.