To understand who the Normans were, we have to go back a little to 911. In this year a rather large Viking chief (reckoned to be so big that a horse could not carry him!) called Rollo accepted the ‘kind’ offer of a large area of Northern France from the then king of France, Charles II (‘The Simple’ ) as part of a peace treaty.

Rollo and his ‘Nor(th) Men’ settled in this area of northern France now known as Normandy. Rollo became the first Duke of Normandy and over the next hundred years or so the Normans adopted the French language and culture.

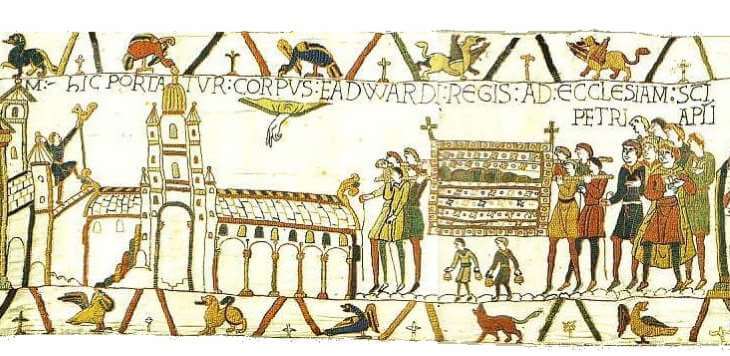

On 5th January 1066, Edward the Confessor, King of England, died. The next day the Anglo-Saxon Witan (a council of high ranking men) elected Harold Godwin, Earl of Essex (and Edward’s brother-in-law) to succeed him. The crown had scarcely been put on his head when King Harold’s problems started.

King Harold also had problems to the north of England – sibling rivalry. Harold’s brother Tostig had joined forces with Harold Hardrada, King of Norway, and had landed with an army in Yorkshire. Harold marched his own English army north from London to repel the invaders. Arriving at Tadcaster on 24th September, he seized the opportunity to catch the enemy off guard. His army was exhausted after the forced march from London, but after a bitter, bloody battle to capture the bridge at Stamford, Harold won a decisive victory on 25th September. Harold Hardrada and Tostig were both killed.

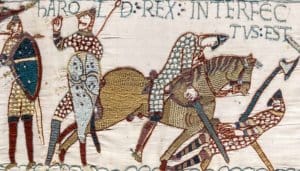

On October 1st Harold and his depleted army then marched the three hundred kilometres south to do battle with Duke William of Normandy who had landed at Pevensey, East Sussex on the 28th September. Harold’s sick, exhausted Saxon army met William’s fresh, rested Norman troops on October 14th at Battle near Hastings, and the great battle began.

At first, the two-handed Saxon battleaxes sliced through the armour of the Norman knights, but slowly the Normans began to gain control. King Harold was struck in the eye by a chance Norman arrow and was killed, but the battle raged on until all of Harold’s loyal bodyguard were slain.

Although William of Normandy had won the Battle of Hastings it would take a few weeks longer to convince the good folk of London to hand over the keys of the city to him. Anglo-Saxon resistance included blocking the Norman advance at the Battle of Southwark. This battle was for control of London Bridge, which crossed the River Thames allowing the Normans easy access to the English capital of London.

This failure to cross the Thames at Southwark required a detour of fifty miles upriver to Wallingford, the next crossing point for William.

Following threats promises and bribes, William’s troops finally entered the city gates of London in December, and on Christmas Day 1066, Archbishop Ealdred of York crowned William, King of England. William could truly now be called ‘The Conqueror’!

This stone below marks the spot at Battle Abbey where the high altar stood on the place where King Harold is said to have died:

The early years of William’s English rule were a little insecure. He built castles across England to convince everyone who was the boss, meeting force with even greater force as rebellious regions like Yorkshire were laid waste (the harrowing of the North).

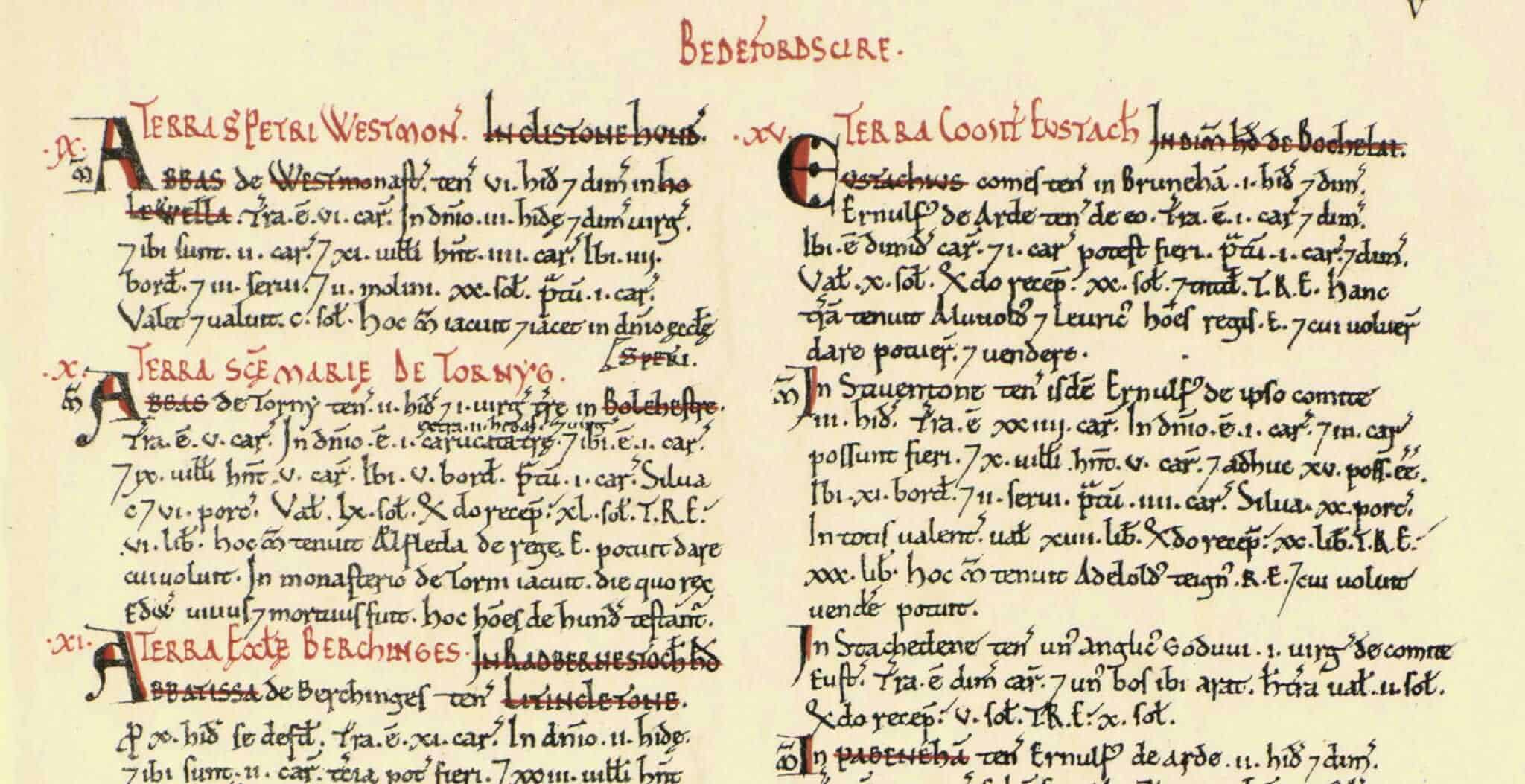

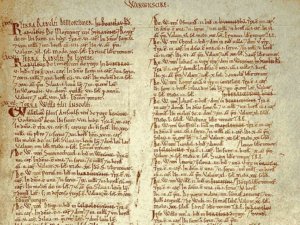

By around 1072, the Norman hold on the kingdom was firmly established. Normans controlled most major functions within the Church and the State. The Domesday Book exists today as a record, compiled some 20 years after the Battle of Hastings, showing all landholder’s estates throughout England. It demonstrates the Norman genius for order and good government as well as showing the vast tracts of land acquired by the new Norman owners.

Norman genius was also expressed in architecture. Saxon buildings had mostly been wooden structures; the French ‘brickies’ at once made a more permanent mark on the landscape. Massive stone castles, churches, cathedrals and monasteries were erected, these imposing structures again clearly demonstrating just who was now in charge.