Today it is common knowledge that Edward II enjoyed the company of both men and women, not that it mattered much in the fourteenth century; God’s anointed were free to make love to whomever they wished, even though (somewhat confusingly) homosexuality was still condemned by the Catholic church.

Edward’s first favourite had been Piers Gaveston, at least until his head was chopped off by the nobility in 1312. A couple of other male suiters followed before Hugh le Despenser, son of the Earl of Winchester, recklessly abused his ‘position’ to carve out a vast domain covering most of south Wales. In a world where land was power, Hugh became someone to be reckoned with. Indeed, nobody was safe from Hugh’s depredations and one could easily lose everything they owned on the basis of a quiet chat between Despenser and the king.

A sensible king should have foreseen the inevitable rebellion. By 1321, the aristocracy’s retinues were camped outside London’s walls, unable to break in, but too terrified of Hugh’s retribution to back down. Inside the walls was the king, unable to compel his besiegers’ disbandment but unwilling to meet their principle demand: to get rid of Hugh. It was Edward’s queen, Isabella who broke the standoff, publicly pleading with the king to exile Hugh for the kingdom’s sake. Edward hadn’t the slightest intention of leaving his BFF in exile, but it bought him time.

The queen again provided the moral justification for Edward’s retribution. Ostensibly travelling to Canterbury, she diverted to Leeds Castle, seat of one of the most prominent rebel nobles, Lord Baddlesmere, and requested to be accommodated. Normally, hosting the queen would have been considered an honour, but Lord Baddlesmere being away from home, Lady Baddlesmere refused. Feigning outrage, Queen Isabella ordered her guards to force their way in. The garrison returned fire, killing several of the queen’s guards.

King Edward now had what he needed to defeat the rebels: moral superiority. Nobody saw the queen as anything but a virtuous and wronged wife, and chivalrous ideals compelled honourable men to defend her honour. The rebels haemorrhaging support, it was a simple matter for Edward to take out the leaders, one by one.

Meanwhile, much to Isabella’s chagrin, Hugh was back, drunk on the elixir of vengeance. If the nobility had feared him before, little now held him back. Aristocrats were dispossessed in their hundreds. When in 1324, Isabella’s brother, the king of France, threatened Edward’s possessions in Gascony, Edward issued an edict commanding the arrest of all French aliens in England and Wales. Having been at loggerheads with Isabella for years, Hugh took advantage of the legislation to settle scores, placing her under house arrest and dragging away her children. As she watched her husband do nothing, her opinion of her husband changed from one of long-suffering distrust to unquenchably violent contempt.

The war was a catastrophe, and Edward was soon begging his wife to intercede with her brother to arrange a peace. He might have been surprised when she agreed, tripped off to France, and rapidly negotiated a peace treaty, on condition that the king’s eldest son be sent to pay homage to the French king. The heir to the English throne under her control, Isabella refused to obey Edward’s instruction to return to England. In France Isabella met up with Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March who had escaped to France after his unsuccessful revolt against Edward (the Despenser Wars) and together they began organising an invasion.

Her army was tiny, consisting of a few hundred mercenaries and a couple of thousand disgruntled English defectors. Her instinct was spot-on that, in their fear of Hugh’s ambition, the nobility would flock to her cause if she promised to replace him with a new king, their son Edward III. Landing on the coast of East Anglia in September 1326, hardly a soul stood in her path to London. Their progress was so rapid that the news reached the king barely in time, sending him into a panic. Stuffing their saddle bags with gold, Edward and Hugh galloped west toward Hugh’s power base in south Wales.

At Chepstow, they chartered a ship, possibly hoping to reach Ireland, but the winds were against them. Five days they bobbed about the Severn Estuary before giving up and docking in Cardiff. They dashed up the road to one of the strongest castles anywhere in England and Wales, to Caerphilly, where terrible news awaited them. Hugh’s father, left to command the defence of Bristol against Isabella, had been executed, his body fed to dogs. The message could hardly have been clearer: Hugh, when caught, would be executed horribly. Edward too can hardly have been unaware of the fate of all deposed kings: they died, without exception.

Had Edward been unaware of the hopelessness of his position, he must have been excruciatingly disillusioned when none of his orders to defend south Wales from the queen were followed. With no prospect of counter attack, it was only a matter of time before, marooned within the castle walls and besieged by Isabella for months, starvation would force their abject surrender. A game changer was vital.

Probably at night, Edward and Hugh sneaked out of the castle for Neath Abbey, hoping in these intensely religious times that a clergyman of sufficient social status could intercede with the queen, but so far had the king’s authority eroded that nothing short of his personal request was likely to succeed. Whether the abbot of Neath did, in fact, meet with Queen Isabella is questionable, but it seems she at least received his message that told her where to look for Edward.

Aware that he’d given away the game, the abbot sent word back to the abbey. Edward and Hugh fled the abbey, hurrying back toward Caerphilly, trying to conceal their passage in the rugged valleys as had so many Welsh rebels before them.

At Llantrisant, they just needed to descend to the bottom of the Rhondda valley, cross the River Taff (fordable at Pontypridd) and scale the other side. They would have seen Caerphilly below them. Or they could have taken a boat down the Nant-Y’r-Aber straight into the castle moat; but it was there at Llantrisant that the hunting party caught up with them.

The reign of King Edward II ended, chased through a Welsh rain storm and pursued by baying dogs.

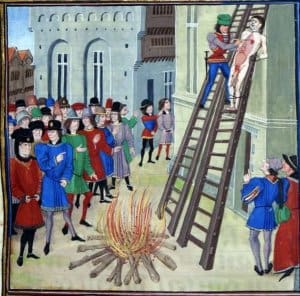

In the following days, Hugh was hanged, drawn and quartered at Hereford. Isabella tucked into a hearty meal as she relished the entertainment. Edward II went the way of all deposed kings. Locked up in Berkeley Castle, he was persuaded to abdicate, then never heard of again. Legend has it that he was murdered by having a red-hot poker thrust up his anus.

By Andrew-Paul Shakespeare. Despite what he freely confesses is an absurdly English name, Andrew-Paul lives in the Welsh village of Abertridwr with his wife and four children. He is a writer, a keen student of medieval Welsh history and runs Flying With Dragons, a website dedicated to Welsh culture for Cymrophiles everywhere.