However little you know about the history of medicine, you’re probably aware that doctors used to prescribe some pretty strange courses of treatment. For centuries they were famously reliant on bleeding, a remedy based on the ancient idea that some illnesses were caused by an excess of blood. Leeches, widely used for hundreds of years, removed only a teaspoonful of blood per application, but physicians sometimes took more drastic measures. By opening a vein (usually in the arm) they could remove several pints at a time if they thought it necessary.

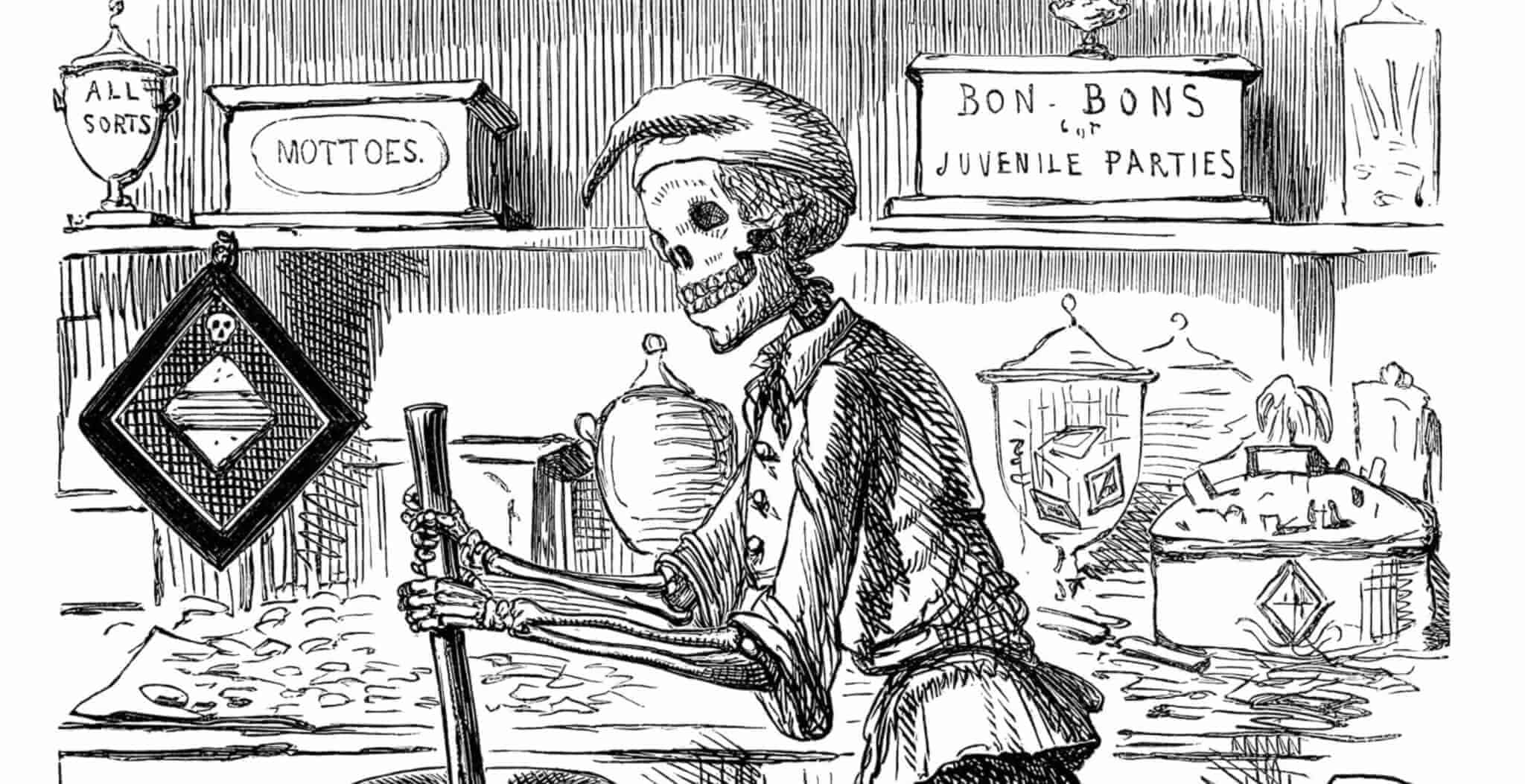

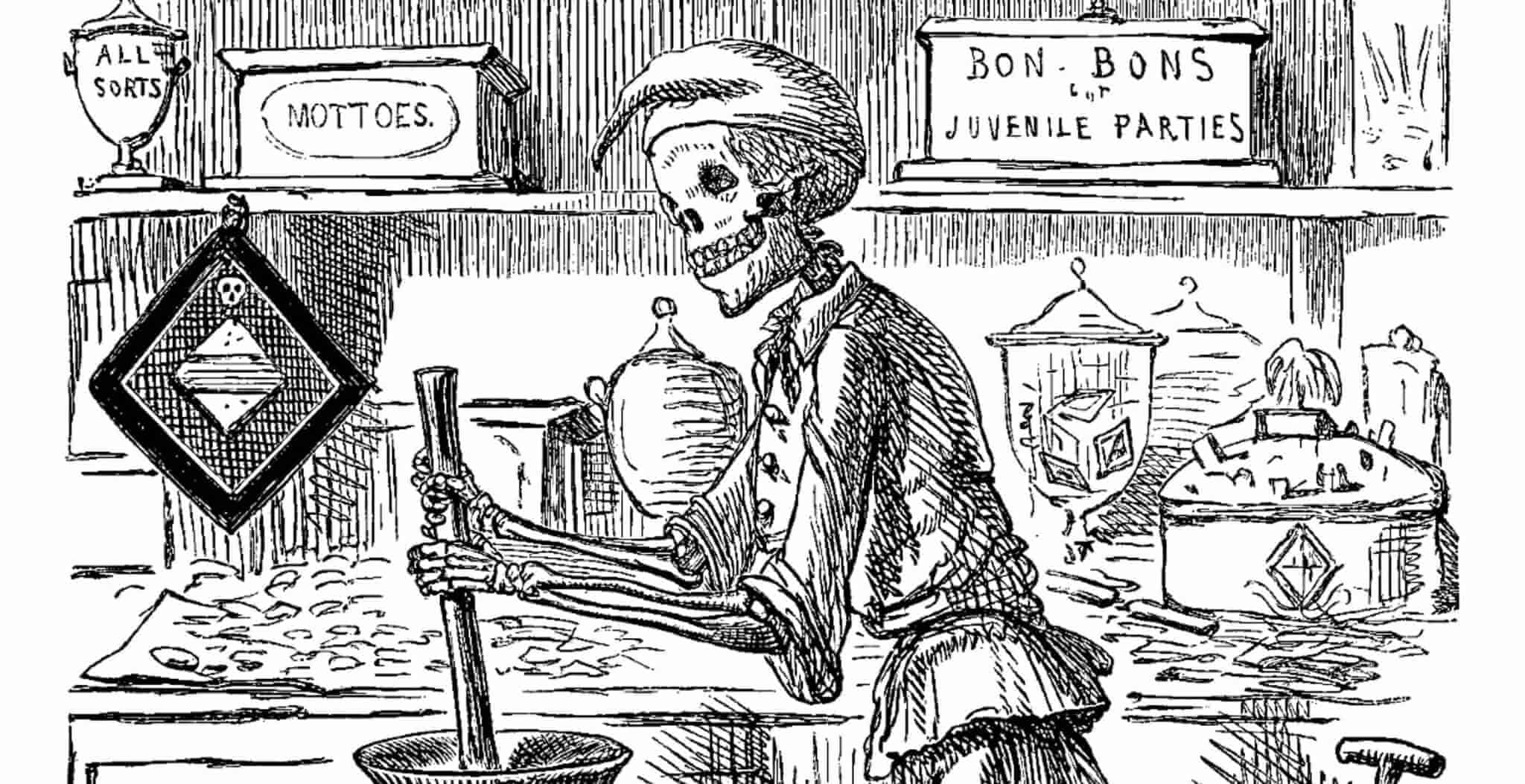

If you were lucky enough to escape a thorough bleeding, taking medicine often wasn’t much fun either. Commonly prescribed drugs included highly toxic compounds of mercury and arsenic, while naturally-occurring poisons such as hemlock and deadly nightshade were also staples of the medicine cabinet. And a volume first published in 1618, the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, offers a fascinating and detailed insight into what used to be considered ‘medicinal’ in seventeenth-century England. It’s a comprehensive list of remedies commonly prescribed by doctors, all of which London apothecaries were therefore required to stock. These ranged from herbs and fruits to minerals and numerous animal products.

The Pharmacopoeia makes fairly extraordinary reading today, since many of the ‘medicines’ it lists are far from pleasant. They include five varieties of urine and fourteen of blood, as well as the saliva, sweat and fat of sundry animals – oh yes, and the ‘turds of a goose, of a dog, of a goat, of pigeons, of a stone horse, of a hen, of swallows, of men, of women, of mice, of a peacock, of a hog, and of a heifer.’ Can you imagine what the average apothecary’s shop must have smelt like?

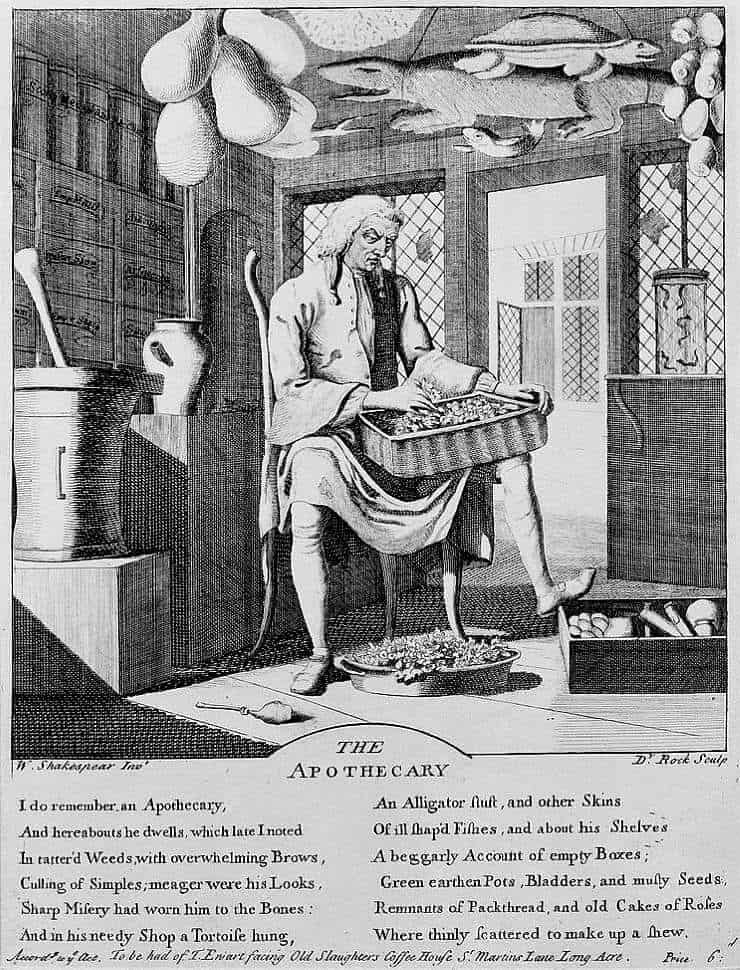

Other items you might have found on the premises included the penises of stags and bulls, frogs’ lungs, castrated cats, ants and millipedes. Perhaps the most bizarre items were discarded nail-clippings (used to provoke vomiting), the skulls of those who had died a violent death (a treatment for epilepsy), and powdered mummy. And yes, that means Egyptian mummy, which was prescribed for a variety of conditions including asthma, tuberculosis and bruising. The London apothecary John Quincy, for example, recommended treating bruises with a powder whose ingredients included Armenian clay, rhubarb and mummy – rather more trouble to get hold of than a tube of ibuprofen gel would be today.

Some of these items must have been fearsomely difficult to get hold of. Hen’s eggs and ox legs presented few difficulties, but where on earth was an apothecary in seventeenth-century London expected to source regular supplies of lion fat, rhinoceros horn or swallows’ brains? Surprisingly, mummy was readily available if you knew the people to ask: the really good stuff was regularly imported from Egypt – although a cheap imitation could be prepared at home by dipping a joint of meat in alcohol and smoking it like a ham. Every bit as effective as the real thing, and a rather tastier sandwich filling.

So much for the early modern pharmacy, but what about emergency care? Some of the treatments on offer for critically ill patients were, if anything, even more unusual. One summer evening in 1702 the Earl of Kent was enjoying a game of bowls in Tunbridge Wells when he fell down unconscious. Luckily a prominent London physician, Charles Goodall, was nearby and arrived on the scene within a few minutes. He found the earl lying on the ground, apparently dead, ‘having neither pulse nor breath, but only one or two small rattlings in the throat, his eyes being closed.’ The signs were ominous, but the doctor left nothing to chance in his efforts to save his patient.

First he bled the earl, removing slightly more than half a pint of blood from his arm. Then snuff was poked up his nostrils and antimonial wine, a toxic brew intended to provoke vomiting, was poured down his throat. The doctor’s plan, orthodox for the time, was to shock the earl back to life by provoking an extreme reaction: sneezing, coughing or vomiting.

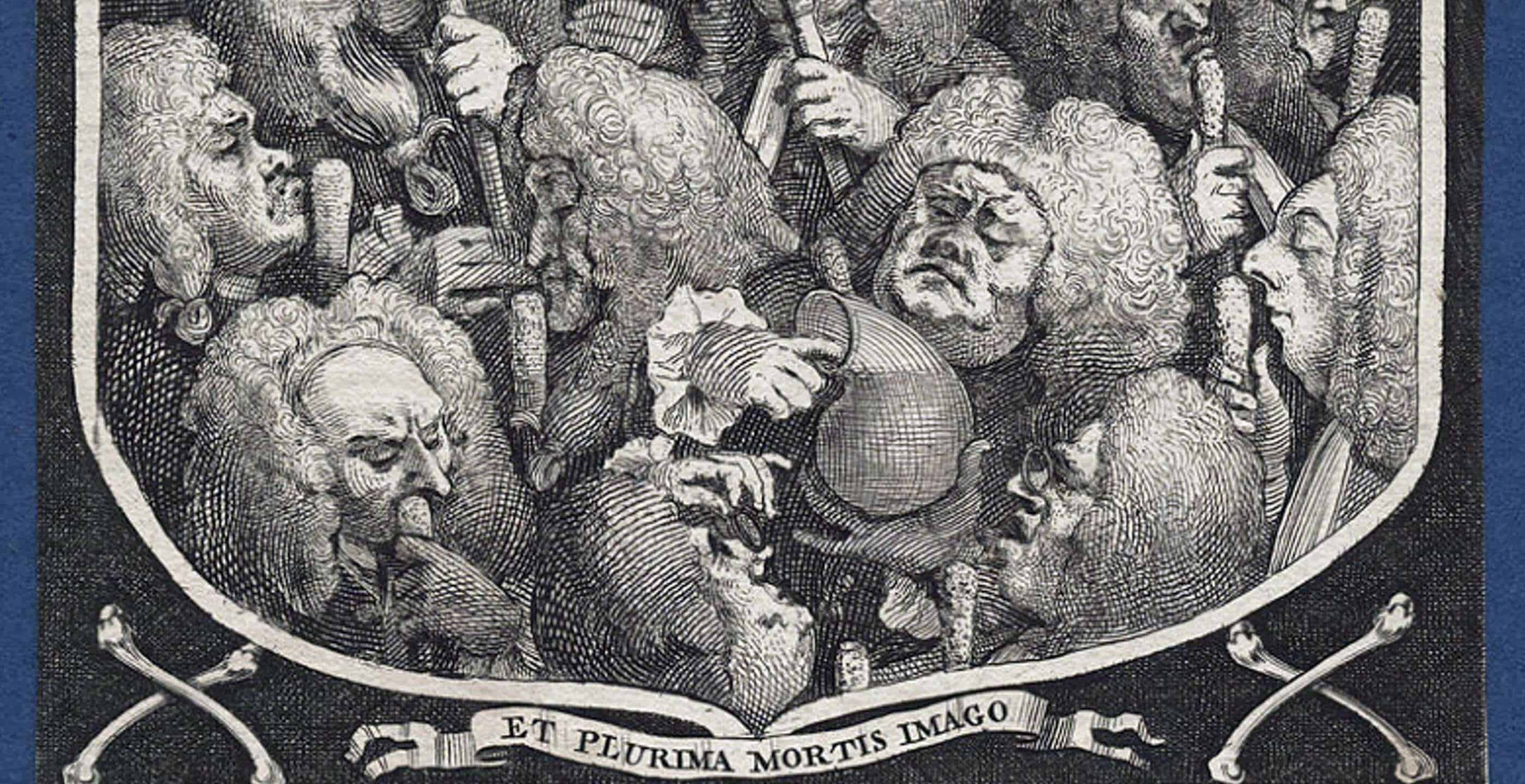

These measures were unsuccessful, so the unfortunate patient was carried indoors and yet more blood taken from him. Next his head was shaved and a blister – a plaster smeared with a harsh caustic substance – placed on top of it. The idea was that this would provoke blistering and so force any toxins out of the duke’s body. Next the resourceful medic administered several spoonsful of buckthorn syrup, intended to empty the bowels. By this point word had got around, and a number of other doctors appeared in the room. One of them suggested that it was time to try something more extreme, so a frying pan was sent for, heated in the fire and then applied red hot to the earl’s head. This did not provoke the slightest reaction, leading several of those present to conclude that their patient was already dead – and they were probably right.

But Dr Goodall was still not ready to give up. At the request of the earl’s daughter his unconscious body was taken to his own chamber and tucked up in a warm bed. The doctors then ordered that tobacco smoke should be blown into his anus. This may sound an eccentric thing to do, but the technique – known as Dutch fumigation – was generally regarded as the most effective means of emergency resuscitation. This time, however, it was no use. The doctors, realising their task was probably hopeless, tried one last thing. The bowels of a freshly-killed sheep were wrapped around the earl’s abdomen – a desperate and thoroughly unpleasant attempt to warm him up.

All proved unavailing, and the doctors finally admitted defeat. ‘Thus fell this great and noble peer, much lamented by all who knew his Lordship’, wrote Dr Goodall in a letter to a friend. It’s likely that the earl had died within a few minutes of collapsing, possibly from a heart attack or stroke. But in 1702, a century before the invention of the stethoscope, it was virtually impossible to be sure that a patient’s heart had stopped – so resuscitation attempts often continued until there was no conceivable doubt that they really were dead.

It’s interesting to note how much medicine changed during the eighteenth century: by 1800, virtually all the strange remedies I’ve mentioned had fallen out of use. Doctors were starting to prescribe substances we’d recognise as medicinal rather than badger fat or rabbit’s paw – and the idea of blowing smoke up a patient’s bottom had certainly had its day.

Thomas Morris worked for the BBC for seventeen years making programmes for Radio 4 and Radio 3. For five years he was the producer of In Our Time, and previously worked on Front Row, Open Book and The Film Programme. His freelance journalism has appeared in publications including The Times, The Lancet and The Cricketer. In 2015 he was awarded a Royal Society of Literature Jerwood Award for non-fiction. He lives in London.

His hilarious book ‘The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine’ traces the evolution of modern medicine through bizarre case reports. Available to buy now.