The story of how the fourth son of a minor 12th century baron rose to be one of the richest men of his day, Regent of England and governing the country on behalf of the boy-king Henry III, is most certainly a true knight’s tale!

The remarkable story of the life of William Marshal is chronicled in the Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal, the only known written biography of a non-royal to survive from the Middle Ages. The poem, composed after his death by an unknown author called John, extols William as being ‘the best knight in the world’, and offers a unique window into courtly life of the time.

William was born around 1146. As the younger son of a minor noble he would have understood from a very early age that he could expect no lands or riches to come knocking at his door, and that he would have to make his own way in life. When he was about 12, William was packed off to his mother’s cousin William de Tancarville in Normandy in France, to begin his training as a knight.

It was here that young William would have learned to use the tools of his chosen profession, which included mastering the latest shock tactic of the day, that of riding into battle atop a horse whilst carrying a carefully aimed war lance. As the saying goes ‘practise makes perfect’, and William trained for seven years to perfect this knightly skill, as well as refining his prowess with the sword and mace.

It was here that young William would have learned to use the tools of his chosen profession, which included mastering the latest shock tactic of the day, that of riding into battle atop a horse whilst carrying a carefully aimed war lance. As the saying goes ‘practise makes perfect’, and William trained for seven years to perfect this knightly skill, as well as refining his prowess with the sword and mace.

It appears that it was not all training and practice however, as William’s biography recalls he earned the nickname ‘Greedy Guts’ during his early years at the Tancarville Retinue. It was however in the final year of his apprenticeship, that the now six foot tall William learned that his father had died and, as expected, had left him no money at all.

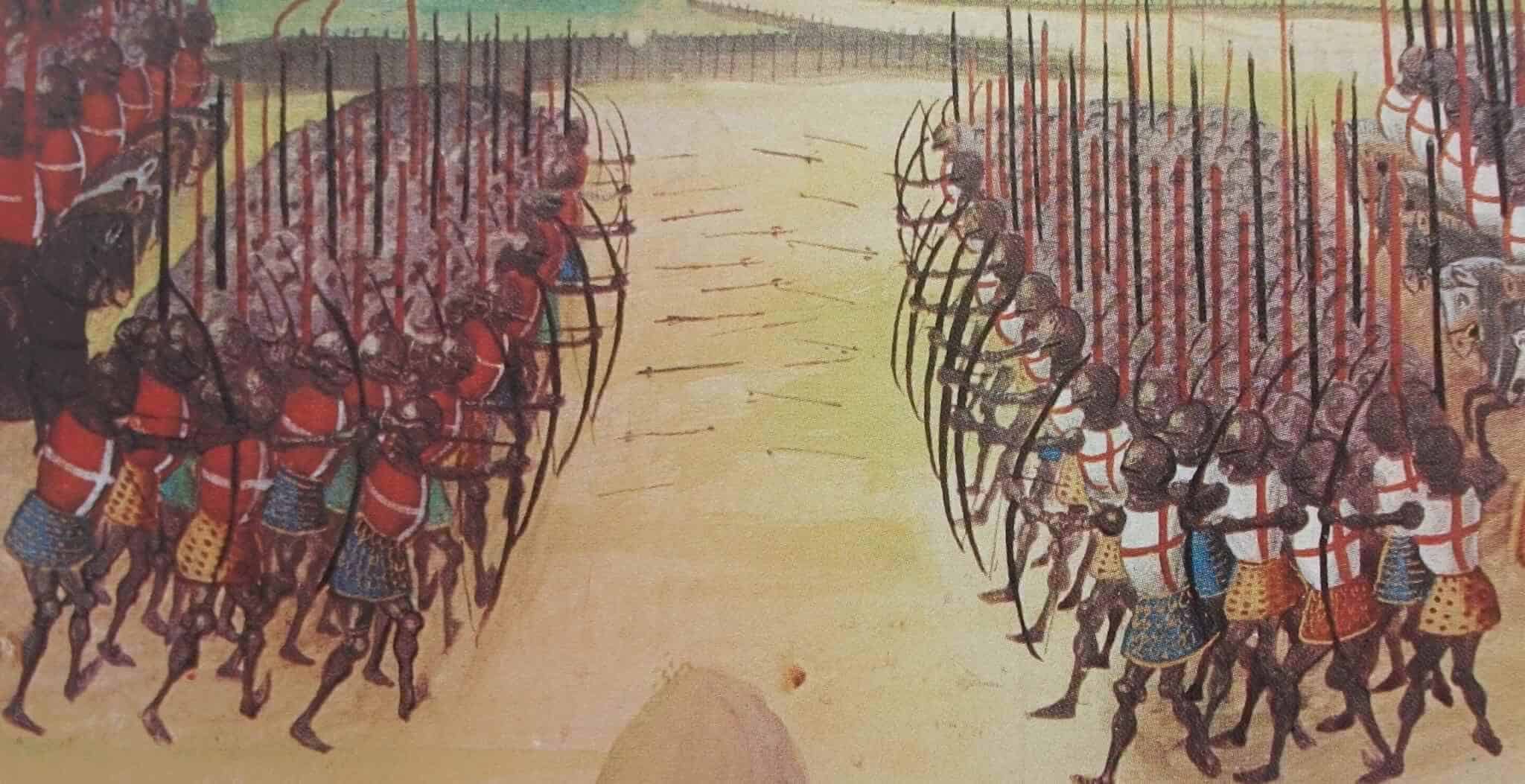

William realised that he had better start earning his living, and as a knight, fighting in tournaments appeared to be the order of the day. In medieval Europe, tournaments were mock battles in which knights could showcase their skills and talent. Typically, hundreds, sometimes thousands of mounted knights carrying war lances would charge headlong into each other and in the melee that followed, swords and maces were used to knock seven bells out of each other. As a ‘training method’ for war, death was not common but did happen on occasion; broken teeth and bones were far more typical.

Luckily for William, the Wembley stadium of the day was just along the road from him, on several acres of fields in Picardy, northern France, Europe’s warrior elite would meet on a regular basis to compete in the tourney. Knights would arrive from all corners of Europe, including Spain, England, Scotland and France, forming teams in order compete. With very few rules and as in real war, the prize was whatever ransom could be extracted from other captured knights, princes and nobles.

By the 1170s William had become somewhat of a superstar of the tournament circuit, and had grown very rich as a consequence. With a combination of his physical strength, horsemanship, prowess with lance, sword and mace, leadership skills and sheer cunning, William had literarily fought his way to the very top of his profession!

Apparently, one of William’s favourite ploys was to grab the reins of his opponent’s horse and drag him from the tournament field, whereupon he would demand horse, armour, weapons, or other valuables for their release. Another favourite tactic of his was to hold his team back from the melee until everybody else was exhausted, picking out the richest prizes before riding onto the field and capturing them.

William’s career entered a new phase when in 1170 he was appointed to the household of Henry, the Young King (crowned king at the age of 15 during his father’s lifetime), the son of Henry II of England. He effectively became player-manager of the young King’s Anglo-Norman tournament team and for the next twelve years they fought alongside each other, aided by a team of up to 500 other knights, winning tourney after tourney. It was William’s job not only to devise the team tactics, but to act as minder to the young King, usually the most valuable prize on the tournament field.

William’s career entered a new phase when in 1170 he was appointed to the household of Henry, the Young King (crowned king at the age of 15 during his father’s lifetime), the son of Henry II of England. He effectively became player-manager of the young King’s Anglo-Norman tournament team and for the next twelve years they fought alongside each other, aided by a team of up to 500 other knights, winning tourney after tourney. It was William’s job not only to devise the team tactics, but to act as minder to the young King, usually the most valuable prize on the tournament field.

In 1182 William and Henry fell out and William left the young King’s tournament team to join the rival team of Philip of Flanders, a move that apparently involved a huge transfer fee!

Their fall out did not last for long, as William was at Henry’s side when he died of dysentery on 11th June 1183. With the approval of the bereaved King Henry II, William set off to complete the crusade his dead master had vowed to make, carrying young Henry’s cross with him to Jerusalem. William spent two years in the Holy Land fighting with King Guy of Jerusalem and the Knights’ Templar.

On his return to England in 1185, William swore allegiance to King Henry II and served as his loyal captain against his rebellious son and heir Richard, soon to be Richard I, The Lionheart. In return the king gifted William the large royal estate of Cartmel in Cumbria.

During a skirmish in northern France in 1189, William came face to face with the undutiful Richard and promptly unhorsed him; rather than putting the prince to the sword he choose to make his point by killing his horse instead.

Shortly after their chance meeting, Henry II died and Richard became king. Although they had fought only days before, Richard rewarded William by giving him the hand of Isabel de Clare, heiress to the estates of Strongbow in England, Ireland, Normandy and Wales. And so at the age of 43 William married his 17-year-old bride, transforming the landless knight from a minor family into a great baron and one of the richest men in the kingdom.

Shortly after their chance meeting, Henry II died and Richard became king. Although they had fought only days before, Richard rewarded William by giving him the hand of Isabel de Clare, heiress to the estates of Strongbow in England, Ireland, Normandy and Wales. And so at the age of 43 William married his 17-year-old bride, transforming the landless knight from a minor family into a great baron and one of the richest men in the kingdom.

In 1190 William was appointed to the Council of Regency which was left to govern the country when the Lionheart departed for the Holy Land at the head of the Third Crusade. He acted as the King’s hands-on general in his continuing wars in France against King Philip II.

William doesn’t appear to have aged like normal folk! In 1197 at the tender age of 50, he scaled the walls of a besieged French castle and held it until re-enforcements arrived. When challenged by the warden of the castle he felled him with a single blow. His physical fitness had helped him outlive three kings, and when King John died in 1216, William was made Regent of England and protector of the nine-year-old Henry III.

Now aged 70, William had just one more fight left in him and at the Second Battle of Lincoln in 1217 he led the King’s army against an invading French force backed by rebel English barons. In true Marshal style, William led the charge, making darned sure that he was the first into the town in order to capture the nobles and set their ransom demands… it seems that you can take the man out of the tourney, but not the tourney from the man!

William’s health finally failed him early in 1219, and whilst on his deathbed he was invested in the order of the Knights Templar. Claiming to have captured more than 500 knights in his career, he apparently signed off with the admission “I cannot defend myself from death”.

But was William really as loyal and honourable as he seems? Well of course he was – the Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal commissioned by his heir, William Marshal II, tells us so. Through it, the legend that was William Marshal has been preserved for posterity.

Published: 4th December 2016