The victory enjoyed by William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings brought the dominance of the Anglo-Saxons to an end and ushered in the Norman era which brought with it, its own trials and tribulations.

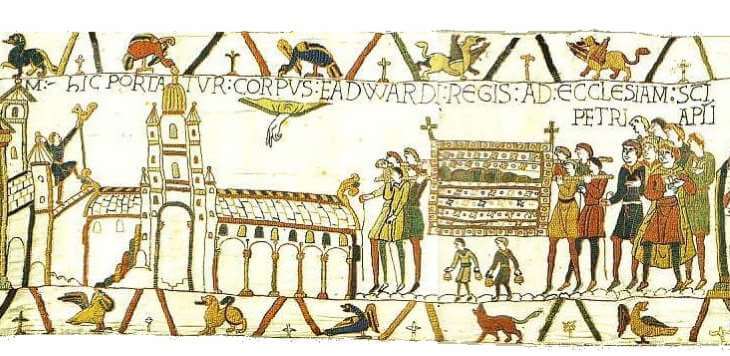

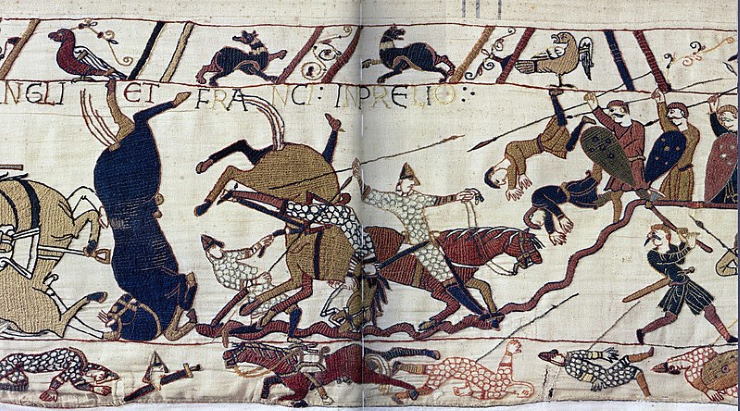

With his escapades famously depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry, William’s successes would help redefine the history of the British Isles, thus making him one of the most influential figures in British history.

His early life however was to be defined by his status as the illegitimate son of the Duke Robert I of Normandy and his mistress Herleva. Born around 1028, he became known as “William the Bastard”, denoting his illegitimacy which impacted his destiny to succeed his father.

Meanwhile, Robert I decided in 1034 to embark on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and convened a council before he left, clarifying William as his heir. This would turn out to be the last the Norman magnate saw of him, as Robert never made it back, passing away at Nicea on his journey home.

With his father failing to have produced a legitimate heir, William’s precarious fate rested in the hands of Norman infighters.

Robert’s death thus propelled a young William into the limelight, however he was fortunate enough to enjoy the support of his great-uncle, Archbishop Robert, in addition to King Henry I of France. With such prominent backers supporting his succession to his father’s duchy, despite his illegitimacy, the stage was set for him to become the Duke of Normandy.

That being said, his succession was not all plain sailing, particularly when his prominent supporter, the Archbishop Robert passed away in 1037, throwing Normandy into a state of political disarray.

Despite receiving support from King Henry, William’s power in the duchy was threatened by rebel forces, with one particularly outspoken critic being Guy of Burgundy.

In 1047, at the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes near Caen, King Henry and William were able to claim victory against the rebel forces, however it was not until 1050 that the young duke was able force Guy of Burgundy into exile.

Meanwhile, power in the duchy was still very much up for grabs, whilst William attempted to consolidate his power by driving out Geoffrey Martel from Maine and securing an overlordship over the Bellême family.

Nevertheless, William was about to experience more rebellion against his inherited authority when the king and Martel alongside other prominent Norman nobles looked to challenge William’s power.

William was now looked upon with suspicion by those seeking to retain their own power bases, including King Henry himself.

Thus, in 1054 he faced an invasion of two parts: the first military group led by King Henry, which William took on for himself and the other, faced down by William’s supporters at the Battle of Mortemer.

The outcome of these battles would include deposing Archbishop Mauger who had been a threat to William’s ducal power and marked a watershed moment for William, as he continued to gain ground and confidence.

Whilst the threats from his enemies seeped into the next decade, the death of both Count Geoffrey and King Henry in 1060, firmly and permanently gave William the upper hand and breathing space to consolidate his power and complete the long process of succeeding his father as Duke of Normandy.

Moreover, assisting him in his growing authority was his marriage to Matilda of Flanders, which secured William a much needed alliance with the country. The union would prove to be most successful, both personally and politically, with the marriage producing four sons to inherit his title as well as solidifying status and connections in continental Europe.

With the fight for his position as duke now over, William could afford to turn his attention to other matters.

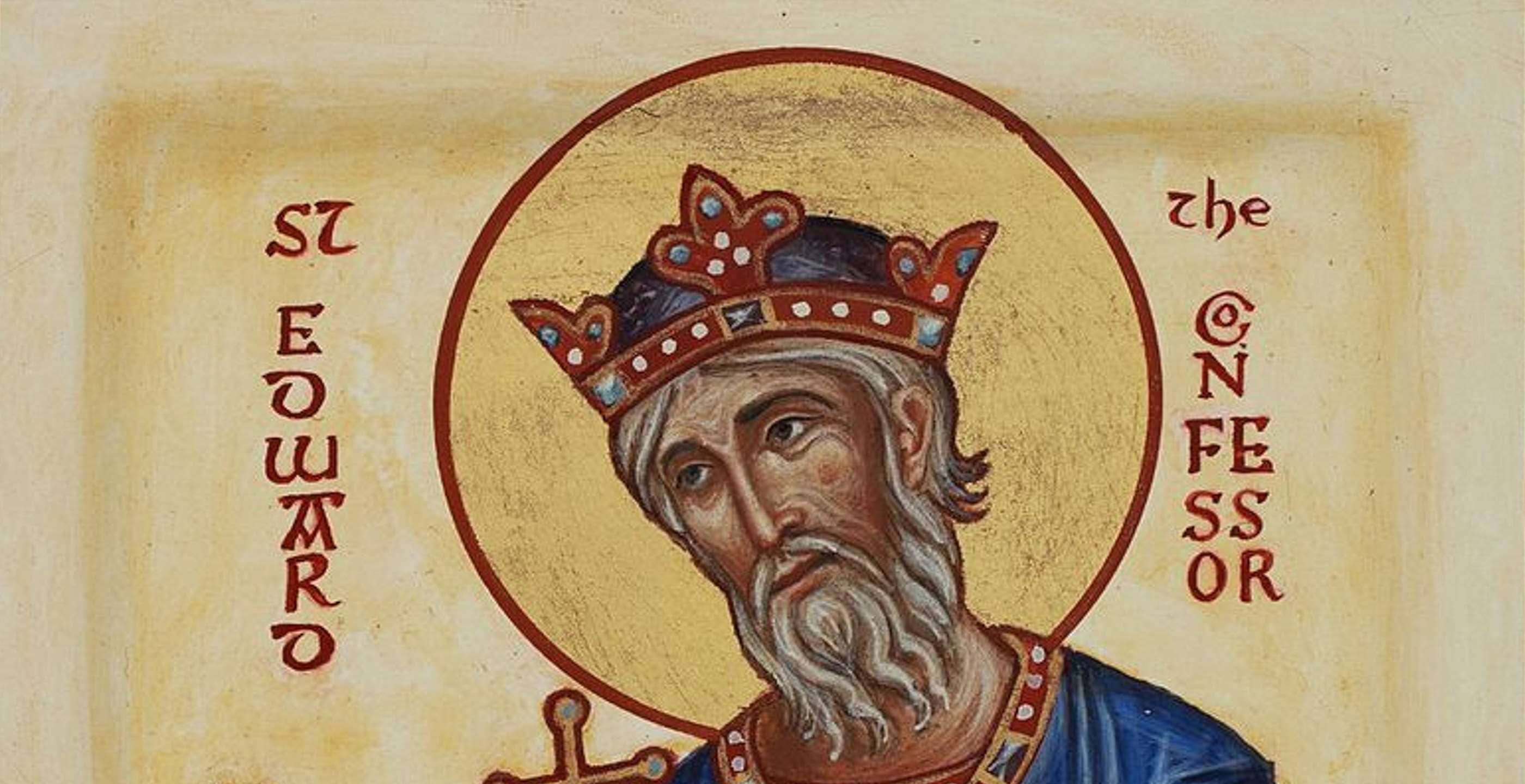

One such issue which was of great importance to him was his position as contender for the English throne, after Edward the Confessor died on 5th January 1066 without children. Whilst William, who was Edward’s first cousin once removed, had been purportedly lined up as heir to the throne, Harold Godwinson had other ideas.

With the Godwin family growing in strength during the latter half of Edward’s reign, their handling of rebellions in both the north of England and in Wales helped to establish Harold as the next successor as Edward lay on his deathbed.

The issue of succession thus reared its ugly head once again with the fate of English monarchy now at stake.

On 6th January 1066, Harold was crowned at Westminster Abbey. Unbeknown to him, he was to be the last Anglo-Saxon English king.

Newly crowned Harold II was not in a comfortable position however, as his claim to the throne was threatened by those within his own family, including his brother Tostig who was in exile whilst King Harald Hardrada of Norway also had a claim to the English throne.

Meanwhile against this backdrop, Duke William of Normandy began making his preparations to invade England and take what had been promised to him.

William had already proven himself to be a strong leader, a military contender and if need be, ruthless in his pursuit of power.

With his eyes firmly on the prize, he set about his military preparations which would take months to complete, including building an extensive fleet in which to launch his invasion of England.

All logistical elements were considered carefully, including not only the value of military material such as swords, spears and arrows, but also other provisions such as food, metalworkers and other goods and men linked to infrastructure, demonstrating William’s commitment to this invasion.

To bolster his position further, the medieval chronicler William of Poitiers stated that the duke also benefited from the support of Pope Alexander II, who had provided him with the papal banner as a sign of approval.

Whilst preparations got underway, in April the sighting of Halley’s Comet was viewed by many to confirm the destiny of William to invade England and was subsequently recorded in the Bayeux Tapestry.

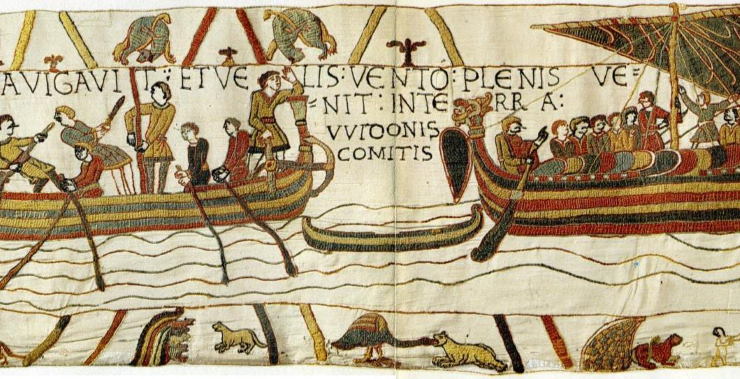

By September, William was ready to launch his invasion having amassed an impressive 600 ships, 7,000 men, including troops from Normandy, Flanders and Brittany who were already awaiting instructions on the estuary of the River Dives.

On 28th September 1066, with favourable weather conditions, William’s fleet made the journey across the channel unopposed and landed at Pevensey.

As soon as they arrived, the Norman invaders set their plan in motion and travelled to Hastings where they raised fortifications and built a wooden castle.

Meanwhile, news of their arrival finally reached King Harold who then journeyed south with a small army at his disposal. Unable to raise troops quickly and still reeling from the Battle of Stamford Bridge near York, his brother Gyrth had attempted to buy more time for the king and his battle-weary troops, however this fell on deaf ears.

On 14th October 1066 at 9am one of the most famous battles in English history commenced: the Battle of Hastings.

On the battlefield, Harold’s troops held the topographical advantage as they were based on a ridge above the Normans, forcing the first assaults by the Normans uphill. Initially William and his men could not break through, as his infantry were met by spears and axes, and were unable to penetrate the English defences.

The turning point came when the left flank of Bretons appeared to be turning back and fleeing downhill, causing some of the English forces to break rank in pursuit. This proved to be a tactical error as it enabled William’s cavalry to cut off the pursuers.

With this tactic proving effective, William decided to employ it twice more during the battle, pretending to flee and then isolating their pursuers, striking the English with arrows as they did.

The final blow for the English came when Harold was wounded on the battlefield, later depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry with an arrow to the eye. He would subsequently die, leading the remaining resilience of English defences to crumble without his presence.

At dusk the battle reached its conclusion, and with it the end of Anglo-Saxon domination.

The battle was a personal and political success for William, as it effectively removed any existing opposition to his claims to the English throne. Not long afterwards his meeting with church leaders and nobility at Little Berkhamstead cemented his position as future king.

Following this meeting, on Christmas Day 1066, William, Duke of Normandy was crowned at Westminster Abbey, ushering in a new era of Norman domination and permanently changing Anglo-Saxon society.

Now with a vast and sprawling empire at his disposal, he would make arrangements for England before returning to Normandy.

Whilst he was now king, William’s position did not go unchallenged as a number of rebellions were launched against his kingship, albeit unsuccessfully, by those who saw it as their duty to fight against Norman hegemony such as Hereward the Wake and Eadric the Wild.

The largest rebellion against William came in 1068, when two Anglo-Saxon lords Edwin and Morcar, led a revolt in the north of England. William responded swiftly, leading his army northwards building castles as they marched, including one in Warwick, a key town in Mercia. The rebellion disintegrated when Edwin and Morcar surrendered after William took control of Warwick.

The winter of 1069-70 proved to be the most notorious period of William’s reign. Faced with local rebellions in northern England encouraged by the Danes and Scots, William employed a ‘scorched earth’ policy known as the ‘Harrying of the North’. William commanded that all crops, herds and food of any kind north of the River Humber, be brought together and burned to ashes. It is estimated that more than 100, 000 people starved to death as a result.

Whilst consistent threats were made and rebel meetings convened, William’s grasp on power remained.

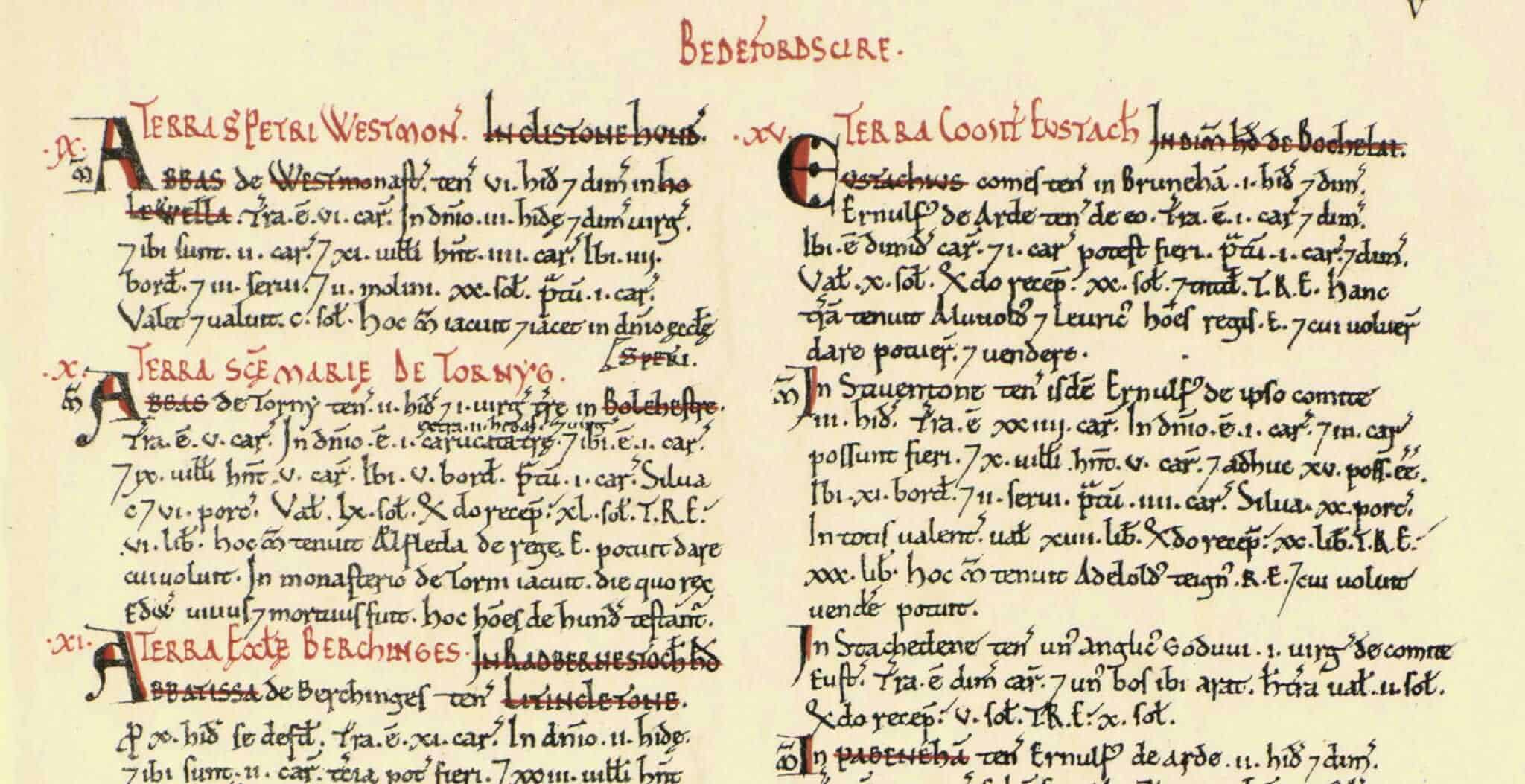

In the latter years of his reign, Anglo-Saxon society shifted with the effects of massive land redistribution to those who were loyal to William and the Great Domesday commissioned by the king himself as a survey of his kingdom. In this time castles were built and a new Norman nobility settled into life in their new lands. The Domesday Book published in 1086, also records that one third of Yorkshire was still a wasteland following William’s horrific ‘Harrying of the North’.

Now with a sprawling kingdom to survey, he spent the remainder of his life on the continent. Passing away in northern France on September 1087, he was buried in Caen.

William’s invasion of England left an enormous imprint on an entire peoples, culture and society, however none had undergone such a transformation as the man himself, beginning his life as “William the Bastard” and ending his life as “William the Conqueror”.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 3rd May 2022