In their famous book, the hilarious ‘1066 And All That’, Sellar and Yeatman maintained that the Norman Conquest was “a Good Thing” as it meant that “England stopped being conquered and thus was able to become Top Nation.” Whether described by historians or humourists, the point about William I of England was that he conquered.

William the Conqueror was undoubtedly a better title than the alternative, the blunt “William the Bastard”. In these more liberated times, Sellar and Yeatman would probably add “as his Saxon subjects knew him”, but it was simply a factual description. William was the illegitimate son of Duke Robert I of Normandy and the daughter of a tanner in Falaise.

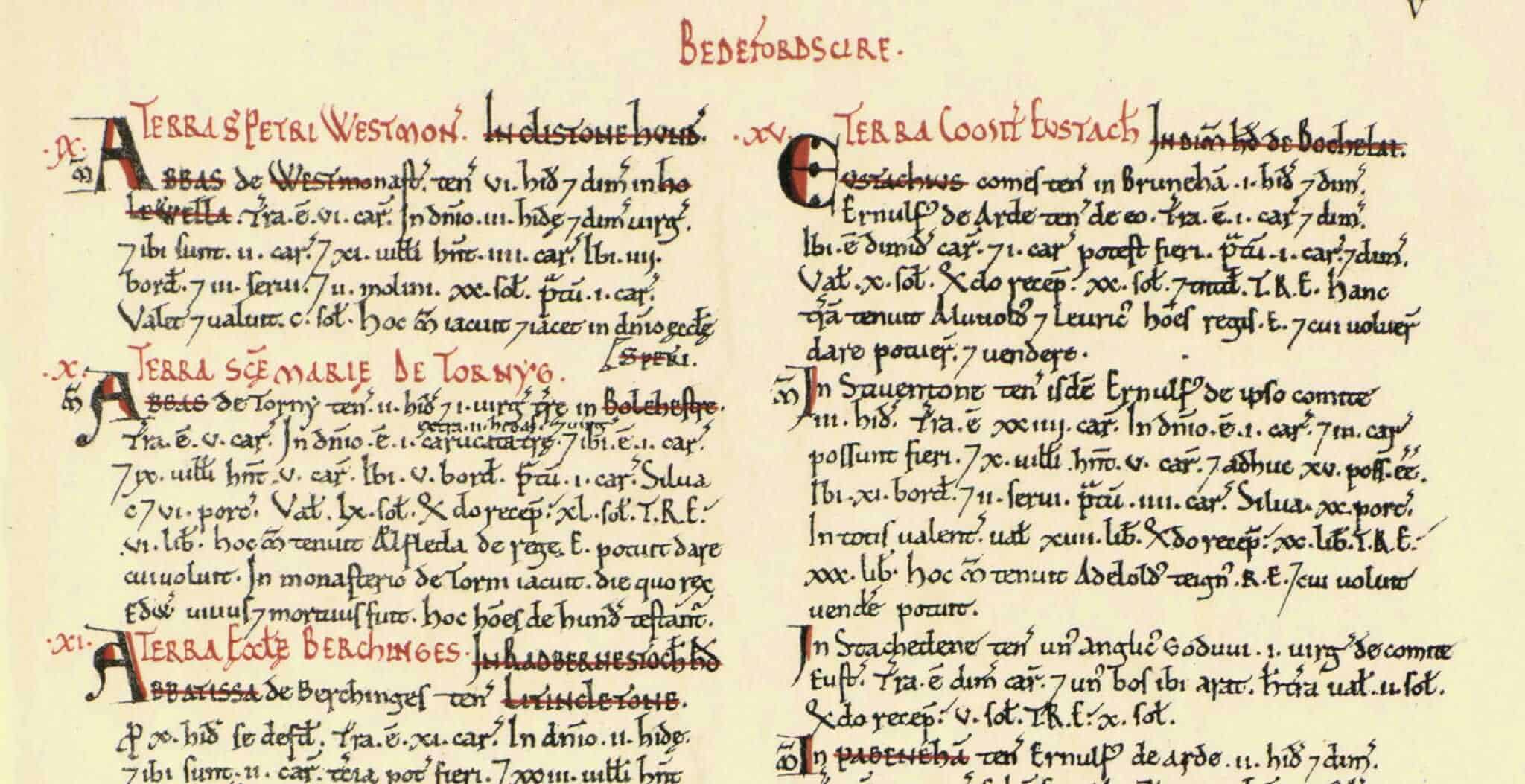

Traditional views of William certainly emphasise his conquering side, portraying him as some kind of violent control freak who wanted to know exactly how many sheep your granny in Mytholmroyd owned and whether your Uncle Ned was hiding any of those rare silver sword pennies in his hose. However, there was one realm that William couldn’t conquer and that was the one ruled by death. After a twenty-year reign during which he gained variable ratings as a ruler on the Norman equivalent of Trustpilot, William was keeping his hand in with a little light raiding against his enemy King Philip of France, when death stepped in and brought his conquering to an abrupt end.

There are two main accounts of his death. The more famous of the two is in the ‘Historia Ecclesiastica’ written by the Benedictine monk and chronicler Orderic Vitalis who spent his adult life in Saint-Evroult monastery in Normandy. While some accounts vaguely state that King William became ill on the battlefield, collapsing through heat and the effort of fighting, Orderic’s contemporary William of Malmesbury added the gruesome detail that William’s belly protruded so much that he was mortally wounded when he was thrown onto the pommel of his saddle. Since the wooden pommels of medieval saddles were high and hard, and often reinforced with metal, William of Malmesbury’s suggestion is a plausible one.

According to this version, William’s internal organs were so badly ruptured that even though he was carried off alive to his capital Rouen, no treatment could save him. Before expiring, however, he had just enough time to set up one of those death-bed last will and testaments that would leave the family arguing for decades, if not centuries.

Rather than conferring the crown on his troublesome oldest son Robert Curthose, William chose Robert’s younger brother, William Rufus, as heir to the throne of England. Technically, this was in keeping with Norman tradition, since Robert would be inheriting the original family estates in Normandy. However, the last thing William should have done was split his dominions. It was too late though. Hardly were the words out of his mouth than William Rufus was on his way to England, metaphorically elbowing his brother out of the way in his haste to seize the crown.

The rapid departure of William Rufus signalled the start of a farcical sequence of events that made the funeral of his father William memorable for all the wrong reasons. There had been an element of farce to William’s coronation too, with the attendees being called from the solemn occasion by the equivalent of a fire alarm going off. However, the chroniclers suggest his funeral rites far exceeded this, ending in a ridiculous situation in Monty Pythonesque style.

To begin with, the room in which his body lay was almost immediately looted. The king’s body was left lying naked on the floor, while those who had attended his death scuttled off clutching anything and everything. Eventually a passing knight appears to have taken pity on the king and arranged for the body to be embalmed – sort of – followed by its removal to Caen for burial. By this time the body was probably already a little ripe, to say the least. When the monks came to meet the corpse, in a spooky re-run of William’s coronation, fire broke out in the town. Eventually the body was more or less ready for the church eulogies in the Abbaye-aux-Hommes.

Just at the point where the assembled mourners were asked to forgive any wrongs that William had done, an unwelcome voice piped up. It was a man claiming that William had robbed his father of the land on which the abbey stood. William, he said, was not going to lie in land that didn’t belong to him. After some haggling, compensation was agreed.

The worst was yet to come. William’s corpse, bloated by this point, wouldn’t fit into the short stone sarcophagus that had been created for it. As it was forced into place, “the swollen bowels burst, and an intolerable stench assailed the nostrils of the by-standers and the whole crowd”, according to Orderic. No amount of incense would cover up the smell and the mourners got through the rest of the proceedings as quickly as they could.

Is the tale of William’s exploding corpse true? While chroniclers were in theory recorders of events, the medieval equivalent of journalists, they, like Herodotus before them, knew the effect that a great yarn had on their readers. There’s nothing new about the public’s interest in gore and guts. If some early writers had been chronicling today, they’d probably have jobs in the gaming industry perfecting the script of “William the Zombie Conqueror II”

What’s more, as many of the chroniclers were clerics, the religious weighting of their accounts has to be considered. It was part of the brief to regard events as aspects of the divine plan. To see the hand of God in the macabre farce that was William’s funeral would satisfy devout readers, particularly the Anglo-Saxon followers of William of Malmesbury’s work. It would also have satisfied a previous occupant of the English throne, whose mocking laughter might have been heard echoing around the afterlife at the news. Harold of England had his revenge at last.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.