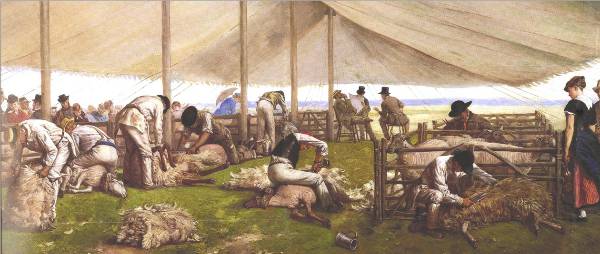

Wool as a raw material has been widely available since the domestication of sheep. Even before shears were invented, wool would have been harvested using a comb or just plucked out by hand. The fuller (one of the worst jobs in history) played an important part in the production of wool by treating it with urine.

The wool was placed in a barrel of stale urine and the fuller spent all day trampling on the wool to produce softer cloth:

Whilst the English did make cloth for their own use, very little of what was produced was actually sold abroad. It was the raw wool from English sheep that was required to feed foreign looms. At that time the best weavers in Europe lived in Flanders and in the rich cloth-making towns of Bruges, Ghent and Ypres, they were ready to pay top prices for English wool.

Wool became the backbone and driving force of the Medieval English economy between the late thirteenth century and late fifteenth century and at the time the trade was described as “the jewel in the realm”! To this day the seat of the Lord High Chancellor in the House of Lords is a large square bag of wool called the ‘woolsack’, a reminder of the principal source of English wealth in the Middle Ages.

As the wool trade increased the great landowners including lords, abbots and bishops began to count their wealth in terms of sheep. The monasteries, in particular the Cistercian houses played a very active part in the trade, which pleased the king who was able to levy a tax on every sack of wool that was exported. The abbeys of Yorkshire in particular boasted huge flocks: Rievaulx had 14,000 sheep; Fountains (the largest) 18,000.

From the Lake District and Pennines in the north, down through the Cotswolds to the rolling hills of the West Country, across to the southern Downs and manors of East Anglia, huge numbers of sheep were kept for wool. Flemish and Italian merchants were familiar figures in the wool markets of the day ready to buy wool from lord or peasant alike, all for ready cash. The bales of wool were loaded onto pack-animals and taken to the English ports such as Boston, London, Sandwich and Southampton, from where the precious cargo would be shipped to Antwerp and Genoa.

In time the larger landowners developed direct trading links with cloth manufacturers abroad, whereas by necessity the peasants continued to deal with the travelling wool merchants. Obviously, by cutting out the middle man and dealing in larger quantities, the landowners got a much better deal! Perhaps this is why it is said that the wool trade started the middle-class / working-class divide in England.

Successive monarchs taxed the wool trade heavily. King Edward I was the first. As the wool trade was so successful, he felt he could make some royal revenue to fund his military endeavours by slapping heavy taxes on the export of wool.

It was also King Edward I who ordered the total extermination of all wolves in his kingdom and personally employed a Shropshire knight, one Peter Corbet to rid England’s western shires – from the grim scourge of the wolf. One of England’s Great Wolf Slayers, Corbet earned the title ‘the Mighty Hunter’, in his endeavours to make the English countryside the ‘perfect natural sheep farm’: free from wolves!

By 1290, it is estimated that there were some 5 million sheep in England, producing around 30,000 woolsacks a year. Just a century later, in the reign of Henry V, almost 63% of the Crown’s total income came from the tax on wool – indeed the beating heart of the national wealth.

Realising the importance of these taxes to his royal coffers Edward III actually went to war with France, partly to help protect the wool trade with Flanders. The burghers from the rich Flemish cloth-towns had appealed to him for help against their French overlord. Although called the Hundred Year War, the conflict would actually last 116 years, from 1337 to 1453.

During this period the taxes that had been levied began to damage the wool trade, which ultimately resulted in more cloth being produced in England. Flemish weavers fleeing the horrors of war and French rule were encouraged to set up home in England, with many settling in Norfolk and Suffolk. Others moved to the West Country, the Cotswolds, the Yorkshire Dales and Cumberland where weaving began to flourish in the villages and towns.

Lavenham in Suffolk is widely acknowledged as the best example of a medieval wool town in England. In Tudor times, Lavenham was said to be the fourteenth wealthiest town in England, despite its small size. Its fine timber-framed buildings and beautiful church were built on the success of the wool trade.

And it wasn’t only Lavenham that grew rich from “the jewel in the realm”, across the country; a total of twenty-six cathedrals as well as thousands of stone churches were constructed. Medieval England could boast ten of the fourteenth largest cathedrals in Europe. And it wasn’t just places of worship… there were bridges, castles, university colleges, guild halls and manor houses all built with the proceeds.

By the fifteenth century, not only was England producing enough cloth for her own use, materials were now being sold abroad. Working in their tiny cottages the weavers and their families transformed the raw wool into fine cloth, which would eventually end up for sale at the markets of Bristol, Gloucester, Kendal and Norwich.

In the 1570’s to 1590’s a law was passed that all Englishmen except nobles had to wear a woollen cap to church on Sundays, part of a government plan to support the wool industry.

Wool production in Britain was of course not just limited to England. Landowners and farmers in both Wales and Scotland recognised the huge profits that could be made from the back of a sheep. Throughout the Highlands of Scotland in particular, some of the darkest days of Scottish history were acted out between 1750 to around 1850.

Known as the ‘Highland Clearances’, landowners forcibly removed tenants from their vast Highland Estates destroying dwellings and other buildings in the process and converting the land from arable to sheep farming. The resulting hardship brought famine and death to entire communities and changed the face of the Highlands forever. So bad was the situation that many Highland Scots fled their own country and sought refuge in the New World, with thousands settling along the east coast of Canada and America.

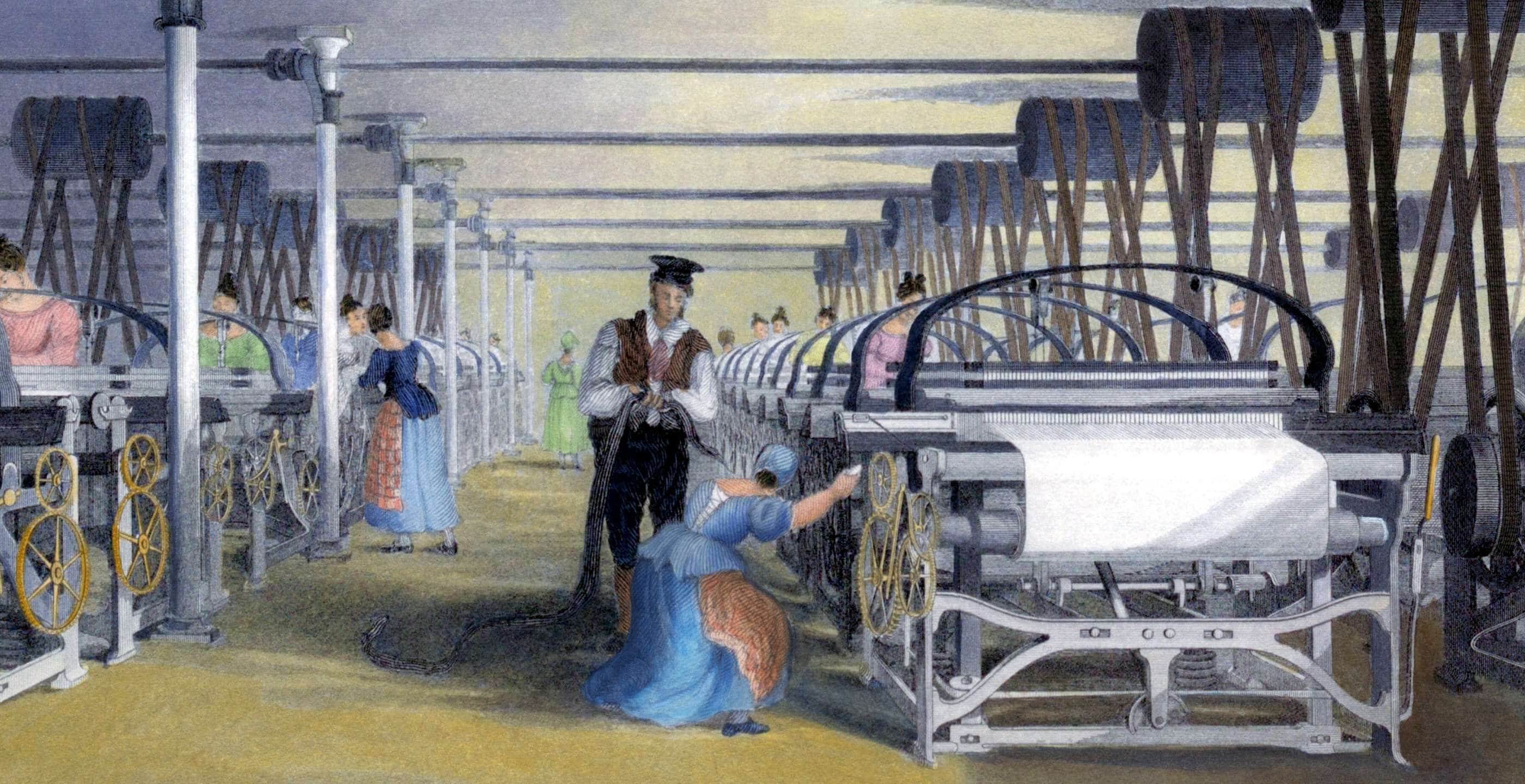

One of the cities at the forefront of a cloth-making industrial revolution was Leeds, which is said to have been built on wool. The industry began in the sixteenth century and continued into the nineteenth century. The construction of various transportation routes like the Leeds – Liverpool canal and later the railway system connected Leeds with the coast, providing outlets for the exportation of the finished product all over the world.

The mighty mechanised Leeds mills, the largest the world had seen, required increasing amounts of raw materials and the ever expanding British Empire would help to feed the savage beast, with wool being shipped in from as far away as Australia and New Zealand. Such trade would continue well into the twentieth century, until the mighty mills finally fell silent as cheaper imports from the Far East flooded into Britain from the early 1960’s.

Today, reminders of the quality once produced by the weavers of Britain can be glimpsed in cloth produced by the three remaining Harris Tweed Mills in the Outer Herbrides. Harris Tweed is cloth that has been handwoven by the Scottish islanders of Lewis, Harris, Uist and Barra in their homes, using pure virgin wool that has been dyed and spun in the Outer Hebrides.

Published: 13th March 2015