The Romans, with typical self-confidence, took it for granted that the people of Italy, nicely balanced at the center of the world, were blessed by the gods, mixing all the martial vigour of the northern barbarians with the sharp wits of the south.

However from the early 2nd century AD onwards, fewer Roman Emperors came from Italy.

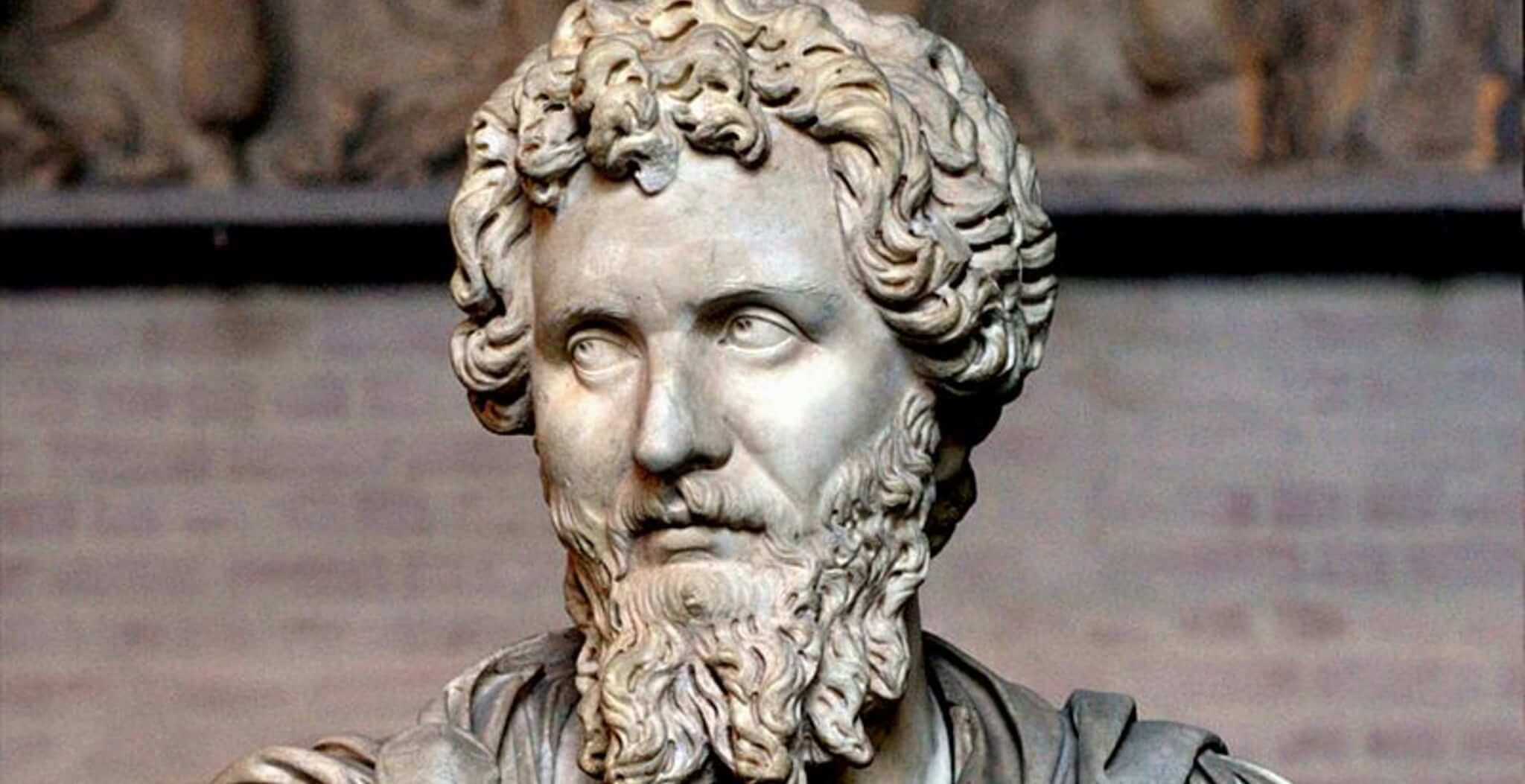

One of these new men, Septimius Severus (emperor from 193 to 211) was born in Leptis Magna in Roman Libya. In the century after Severus, another career soldier, this time from the Balkans, became Caesar: Constantius I, or Constantine Chlorus (Constantius the Pale) as he was known.

Although they lived in different centuries, the need to defend the frontiers of the Empire brought these two hard men to the edge of the Roman world in the twilight of their respective careers: across the sea to Britain, “that greatest of all islands under the Sun, which the Ocean surrounds” and then north to the military base at York (Roman Eboracum) where age, ill health, and perhaps the notoriously damp climate, finally caught up with them.

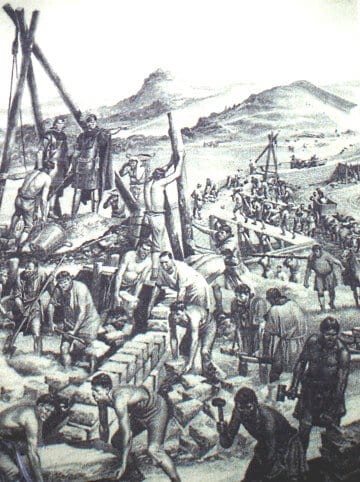

To the north lay the great Wall ordered by the Emperor Hadrian in 122 to mark the limits of the Empire and effectively choking the island at its narrowest part. As far as the Empire was concerned, its purpose was “to separate the Romans from the barbarians” who lived in the mountainous north, so that successive emperors could keep “the better part” of the island safe – although contemporary opinion rather unkindly dismissed even this as “not much use to them”.

Britannia clearly had an image problem. But for the Empire’s commanders wondering how to blood new recruits, it was also one of their more reliable training grounds.

The result was that the province hosted a disproportionately large garrison, which always carried a risk because the local governor could use this force to take advantage of confused conditions elsewhere in the Empire.

This was exactly what happened late in the second century, when Decimus Clodius Albinus declared himself emperor and crossed the Channel with his British legions – dismissed in the most insulting terms as “island-bred” by a Roman civil servant – only to be defeated in southern Gaul by legions under the command of a rival emperor, Septimius Severus.

In 208, this now undisputed master of the Roman world brought his two cock-fighting, chariot-racing sons with him to Britain, in the hope that some experience in a province notoriously short on pleasure would toughen them up.

The younger son, Geta, was left in nominal charge of the Imperial administration, while the elder brother, Caracalla, accompanied the emperor across “the rivers and the earthworks which marked the boundary of the Roman Empire in this region” This was a show of armed strength designed to impress the natives, but the Caledonian and Maeatae tribes just slipped away, leaving the Romans to blunder on through mist and water. The physical demands of the campaign proved too much for the aging and gouty Severus, and he returned south of the Wall to die in York on 4th February 211, after a reign of eighteen years. The Imperial headquarters lay under today’s York Minster. His body was cremated there and the ashes returned to Rome.

In 305, another emperor came to York on what also turned out to be his last journey. For Constantius Chlorus – emperor of the Western half of an empire that had grown so big it now needed two rulers – this was actually his second visit to Britain.

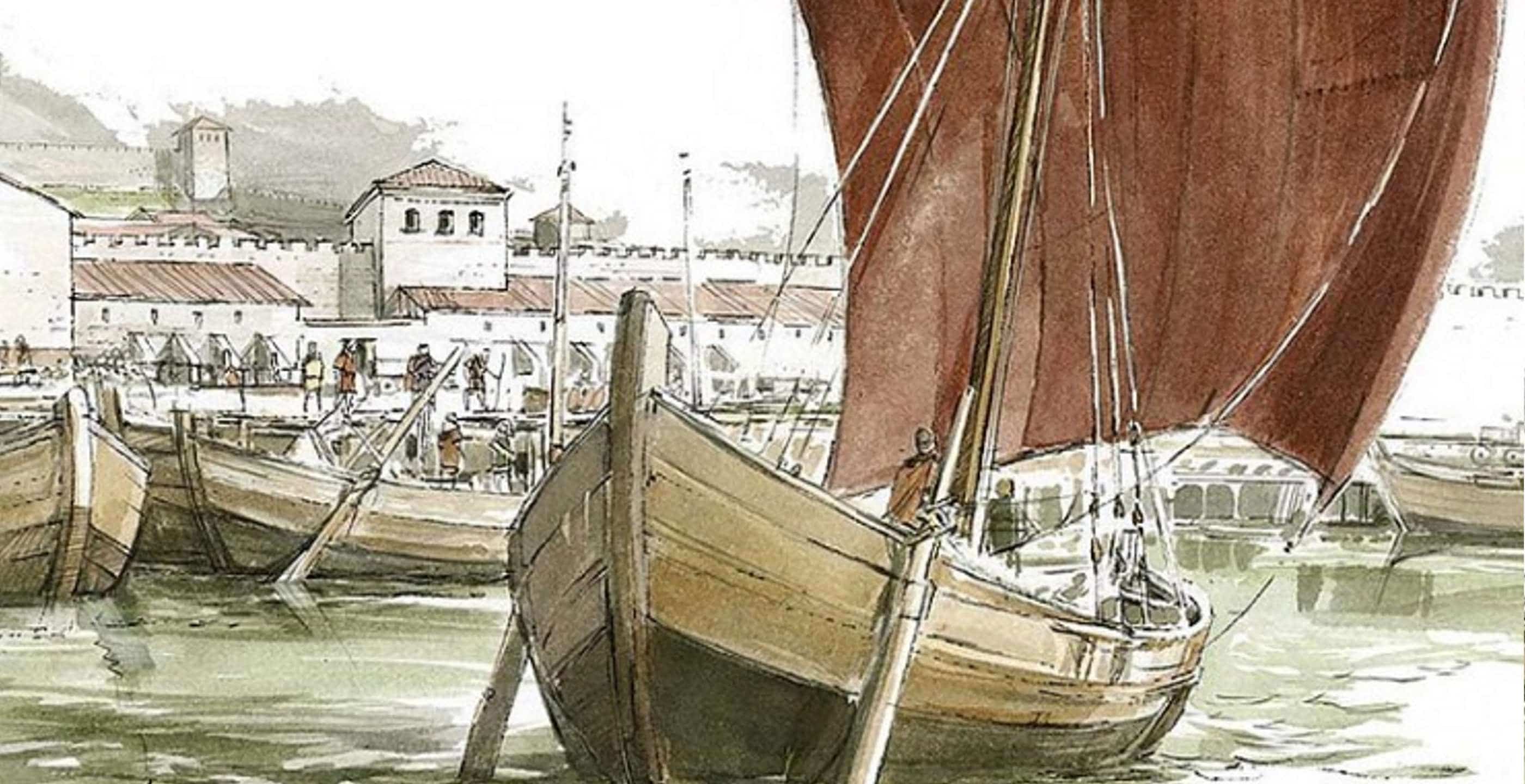

The first was nine years earlier, when Constantius took on yet another would-be emperor of the Roman world. This was Carausius, a river pilot from the Low Countries who rose through the ranks of the Channel fleet to set himself up as the ruler of an independent British empire.

The forces of the official empire first captured Carausius’ naval base at Boulogne, on the Gaulish side of the Channel, which undermined his credibility enough to trigger his assassination in 293. This, however, only cleared the way for his finance minister, Allectus, to step into the dead man’s shoes.

It took three more years before Constantius launched his cross-Channel invasion to remove Allectus. Foul weather delayed his departure, allowing his deputy Asklepiodotus to land first on the south coast and defeat Allectus so soundly that the fighting was all over when Caesar finally arrived.

Late arrival or not, Constantius Chlorus made sure he got the credit for recovering Britannia and issued veterans with a gold campaign medal on which he, Caesar, featured prominently. The message to any foot-dragging Britons was clear: their flirtation with separatism was over, with Constantius as a liberator who restored to them “the eternal light of Rome”.

His second trip to Britain, which came a decade later, turned into a rerun of Severus’ campaign almost a century earlier. Again, the security threat came from tribes from north of the wall, and again they proved no match for Roman legions led by the emperor and his son.

But just like Severus before him, the emperor’s triumph proved short-lived and he too returned south, to die in York on 25th July 306.

Once again, the legions in York were the first to acclaim a dead emperor’s son as his successor. The Imperial spin doctors commanded Britain to consider itself “happier now than all other lands” because it was the first to greet its new master – Constantine the Great, destined to become the first Christian emperor of the Roman world.

Tours of historic York

For more information concerning tours of tours of historic York, please follow this link.

Marie Hilder is a freelance writer.