Fans of classic British films will know the 1957 box office success The Admirable Crichton, starring Kenneth More and Diane Cilento. Based on a play by Scottish writer J.M. Barrie, best-known as the author of Peter Pan, the plot of The Admirable Crichton follows the fortunes of an upper class family marooned on a desert island with their butler Crichton and maid Eliza.

The old rules of class and hierarchy are useless in this new environment, and it is Crichton and Eliza who have the practical skills necessary for survival. Crichton becomes leader of the group through his superior ability and the family ends up contentedly following his orders. A bit predictably, Crichton wins the hearts of both Eliza and Mary, the daughter of the Earl of Loam. Of course the idyll has to come to an end and the class system reasserts itself, though Crichton and Eliza escape with a stash of pearls they sensibly acquired on the island.

Describing someone who is multi-talented as another “Admirable Crichton” existed long before the film, or even Barrie’s play, which dates to 1902. Who was the original “Admirable Crichton” and what made him admirable?

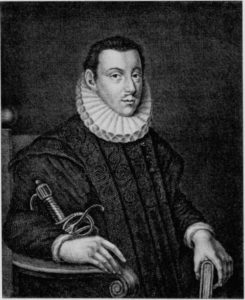

James Crichton was born in 1560 in Perthshire and died in Italy in his twenty-second year during an argument in the street with Vincenzo Gonzaga, the son of Crichton’s employer, the Duke of Mantua. In his few brief years on the planet Crichton had become a noted scholar, linguist, swordsman, horseman, musician and poet. He also had outstanding good looks. Everything, in fact, that was required for a man of the Renaissance.

Everyone adored the handsome young Scotsman, son of the Lord Advocate of Scotland. Everyone but Vincenzo Gonzaga, that is, and perhaps it’s not entirely surprising given that one of Crichton’s skills had been to charm Gonzaga’s own mistress. Allegedly, that’s where he had been on the night he was accosted by Gonzaga and his party, all masked and ready for a fight.

Although original documentation relating to James Crichton is scant, biographies of him were numerous until the 19th century. From these it is possible to piece together some of the facts about the brief life of this polymath who attended St. Andrews University from the age of ten. While it’s true that scholars did go to university earlier than students do now, this very early start marked him out as a prodigy.

At St. Andrews, Crichton probably studied under the famous scholar George Buchanan, who was also tutor to the young king James VI of Scotland and who was responsible for alienating him from his mother Mary Queen of Scots. Buchanan, unsurprisingly, had a reputation for brutality.

Crichton left the university at the age of fourteen having gained bachelor and masters degrees. He travelled to France where he studied at the College de Navarre. Here, according to his 17th century biographer Thomas Urquart, Crichton issued the first of many challenges, that he would answer questions “in any science, liberal art, discipline, or faculty, whether practical or theoretic”. What’s more, he offered to do so in any one of the twelve languages in which he was proficient!

On this occasion his oratory is said to have drawn the admiration of four professors. While in France, he also participated in tilting and other feats of arms and generally established his reputation as an outstanding talent of the Renaissance. His biographers claim that it was at this time that he gained the description “Admirable”.

Crichton also served in the army of the king of France. After impressing the great and the good of that country, he travelled to Italy, the centre of European culture. While in Rome he is credited with making a great impression on the Pope, the cardinals and Roman scholars with his oratory. Then he possibly spent time at Genoa before moving on to Venice, a noted place of opportunity for ambitious young men.

It’s at this point in his life that some biographies begin to hint that all was not quite as it seemed in the life of this golden youth. Patrick Fraser Tytler, for instance, who published a biography of Crichton in 1819, comments that: “At this time Crichton, notwithstanding the excessive admiration which he had attracted, and the popularity which his talents commanded, appears to have been labouring under some severe distress of mind, but from what cause it may have originated, is not easily discoverable.”

Crichton’s intellectual skills may have brought him great fame but it’s possible he didn’t have the means to support himself, despite apparently coming from an influential Scottish family with links to royalty through his mother, Elizabeth Stewart. His father held lands in Cluny in Perthshire and Eliock in Dumfriesshire and other relatives were senior churchmen. However, at least one biographer suggested that his entire background was made up. This appears to be completely unjustified.

What is known is that on arrival in Venice, Crichton sent some poems to Aldus Manutius, a member of the family of printers who founded the famous Aldine Press. Aldus was so impressed by the genius of Crichton that he introduced him to the Doge of Venice and the Senate, who were also astounded by his ability. Crowds gathered to hear him talk and dispute. Crichton had become a celebrity intellectual.

At the University of Padua, he started the proceedings with a poem dedicated to the city and then treated the assembled to a six-hour long dispute on Aristotle and Plato. When he failed to turn up for another event with the Bishop of Padua (Aristotle and mathematics, a real crowd-puller!) it gave his critics a chance to bring Crichton down a peg or two.

His reputation was restored in Mantua, though it wasn’t through his ability to talk. It was by taking on a professional swordsman who travelled about challenging people to duel with him for purses of money. He had already killed three swordsmen in the city when Crichton took up his challenge.

The professional swordsman was no artiste – he attacked with ferocity and Crichton had to defend himself strongly before he could overcome his opponent, killing him with three sword-thrusts. It was this as much as his reputation as an orator that inspired the Duke of Mantua to hire Crichton, some say as a companion for his son Vincenzo.

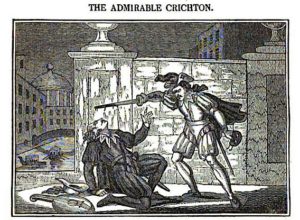

Although he was only in the Duke’s employ for a few months, Crichton wrote plays and poems and enhanced his reputation as a musician during this period. His death was as dramatic and extraordinary as his life. On 3rd July 1582, on his way back from visiting his mistress (some biographers add the touch that he was strumming a guitar), Crichton was accosted by the masked street gang led by Vincenzo Gonzaga.

Crichton managed to fight so successfully that the majority of his attackers fled. The last one was unmasked as Vincenzo Gonzaga himself, causing Crichton to fall to his knees and offer his sword to his opponent, who coolly took it and stabbed Crichton through the heart.

The drama of James Crichton’s life has echoes in the work of playwrights such as Shakespeare. A tale of talented youth cut off in its prime had appeal for both the Elizabethans and the Victorians. This makes it hard to disentangle fact from fiction in contemporary and later reports. Even the description of Crichton by Aldus Manutius has been under scrutiny as he described another talented young scholar, Stanislaus Niegoseusky, in similarly glowing terms.

Crichton was buried in Mantua the day after his death and he has a memorial in Sanquar, Dumfriesshire, the Scottish county where the Crichton name is still well-known. His works are little known beyond a few scholars today, but in 2014 an English translation of his poem “Venice”, originally written in Latin, was released by poet Robert Crawford and photographer Norman McBeath.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.