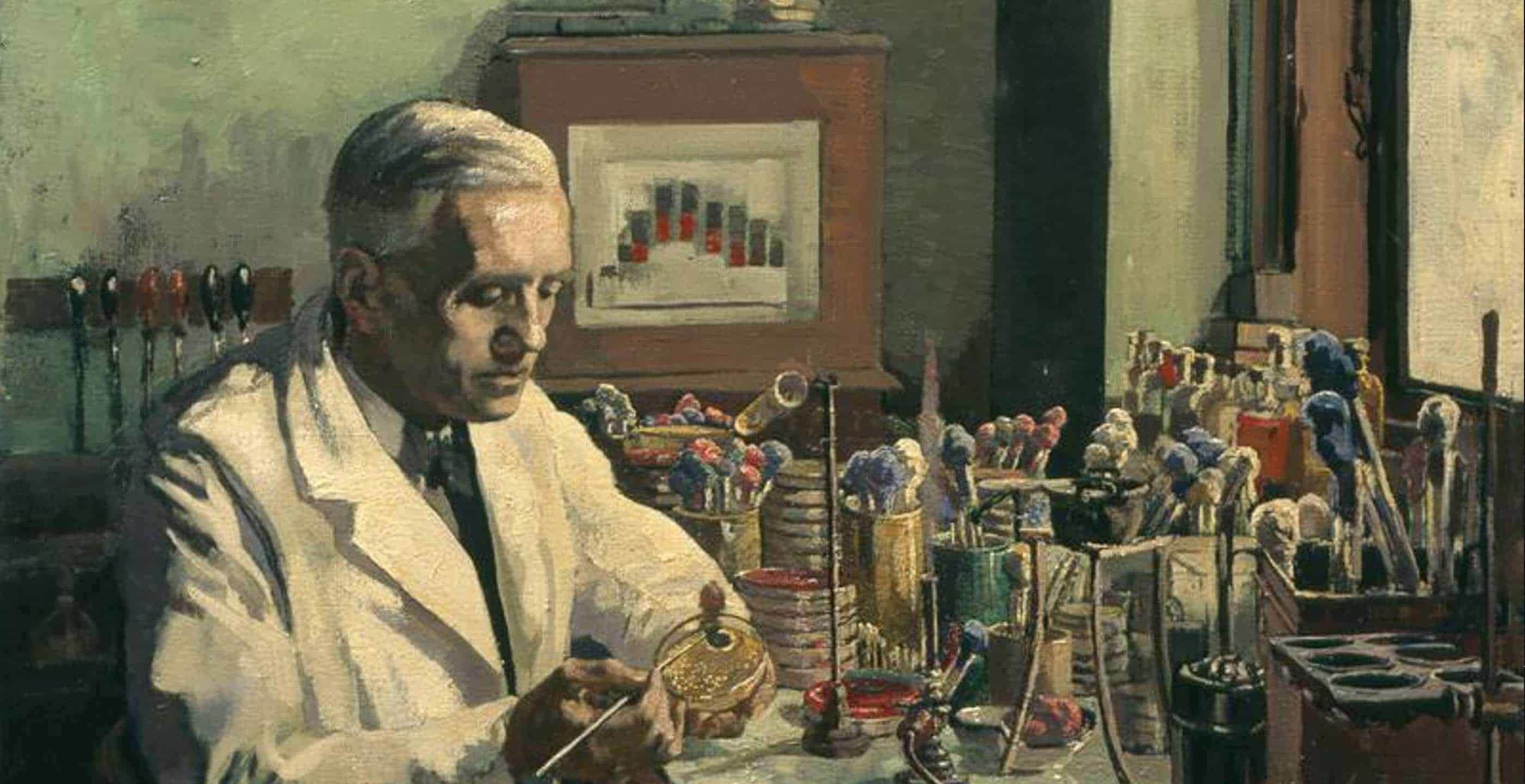

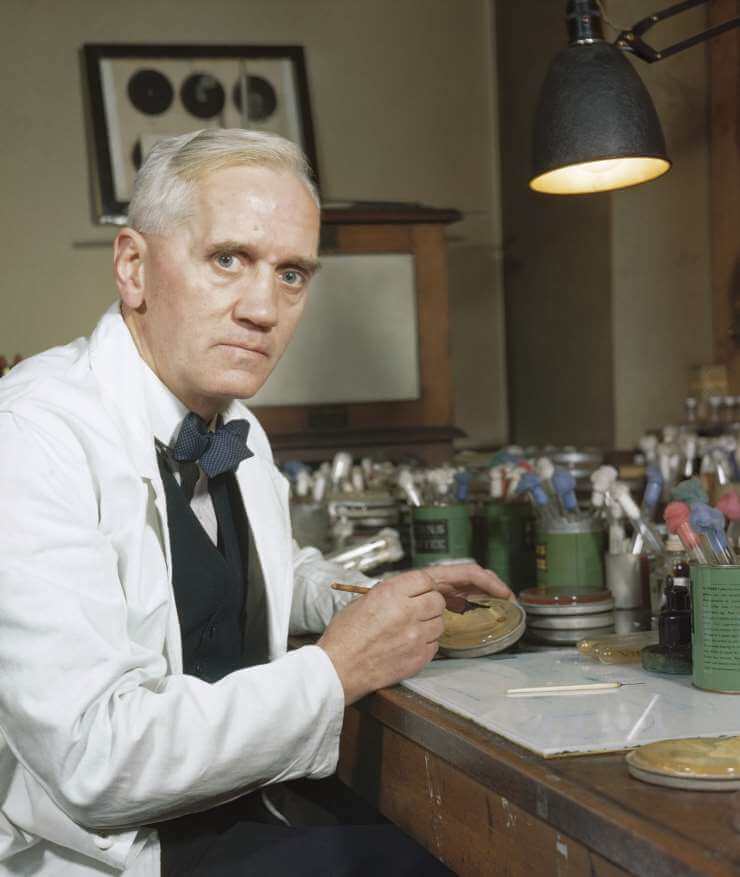

On 6th August 1881 Sir Alexander Fleming was born; in later life he would become a pharmacologist and Nobel Prize winning physician, and go on to discover penicillin. In the field of medicine he excelled, writing numerous articles on bacteriology and immunology but is best known for his discovery of the world’s first antibiotic. Fleming’s breakthrough had an enormous impact not only on the world of science but for mankind and our use of medicine.

He was born in Ayrshire in Scotland at Lochfield Farm, the son of Hugh Fleming, a farmer and Grace, Hugh’s second wife, the daughter of a farmer in the area. Hugh Fleming had already fathered four children during his previous marriage and was an old father to Alexander, unfortunately passing away when he was only seven years of age.

His early education was spent at Louden Moor School, Darvel School and finally Kilmarnock Academy where he had earned a two year scholarship. After his initial education in Scotland he moved to London to live with his older brother, Thomas Fleming.

Whilst living in the capital, he finished his secondary schooling at the Royal Polytechnic Institution and initially worked at a shipping office for four years in order to earn a living. However, fortunately for the now twenty year old Alexander, he inherited money from his uncle and on the advice of his older brother Tom, who was already working as a physician, he entered the profession, enrolling at St Mary’s Medical School at London University.

Meanwhile, Fleming had been serving in the London Scottish Regiment of the Volunteer Force since 1900 as a private, and when he joined the university he became a member of the rifle club at his medical school. A keen enthusiast for the sport, the captain of his club had wanted Fleming on his team and as a way of coercing him to stay, had contacted the research department at St Mary’s, suggesting that Fleming join the department. By 1906, Fleming had graduated with distinction and subsequently joined the research team under the guidance of Sir Almroth Wright, an important figure in vaccine therapy, under whom he served as assistant bacteriologist. This would prove to be a vital stage in the development of his career and in his understanding of medicine, working in a revolutionary field of science and research. Two years later, Fleming had gained a Bachelor of Science degree in Bacteriology earning a Gold Medal and later becoming a lecturer at the university.

Whilst Fleming was establishing a career for himself, he married Sarah Marion McElroy, an Irish woman who worked as a nurse. They married in 1915 and had a son Robert born in 1924 who would later follow in his father’s footsteps and practice medicine. Until the outbreak of the First World War Fleming established a private practice, specialising in the treatment of venereal diseases, becoming one of the first in Britain to use a new drug that proved effective in treating syphilis.

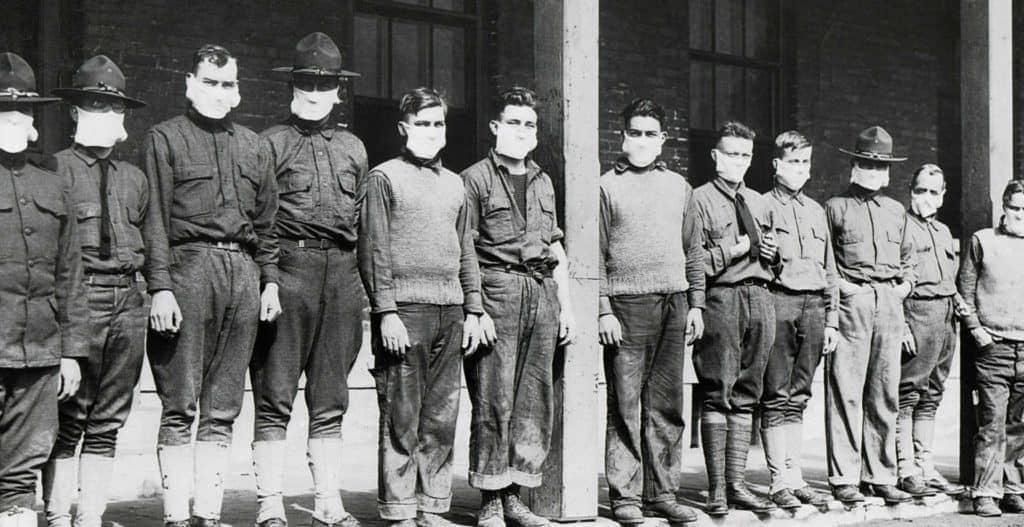

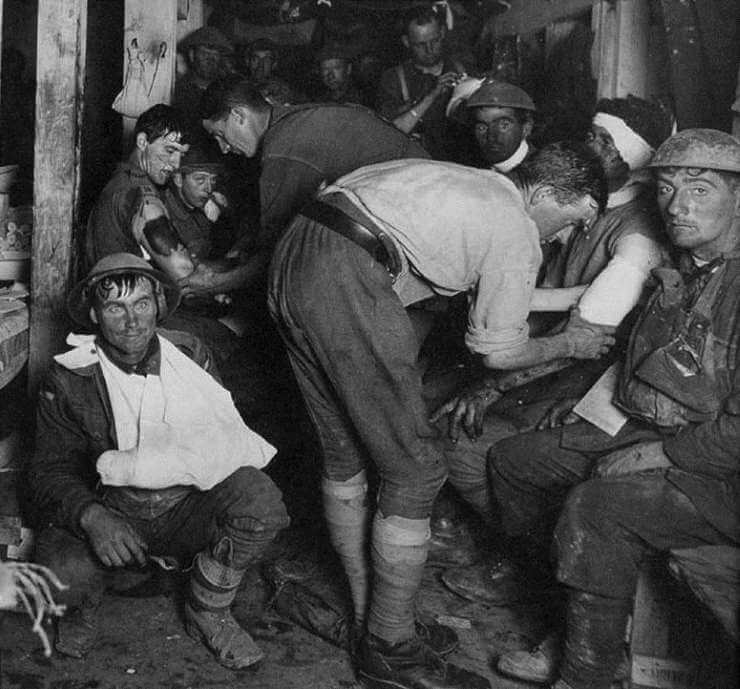

As a member of the Scottish Regiment in London and a keen shooter, his subsequent participation in the war was indisputable. He would go on to serve as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps and was also mentioned in Dispatches. With his impressive credentials, his assistance was needed on the battlefield and so Fleming, along with many of his peers worked at the Western Front in France in the battlefield hospitals.

Fleming worked as a bacteriologist in a makeshift lab in Boulogne in France, studying wound infections and in the process discovering that the commonly used antiseptics were not having a sufficiently beneficial effect on the body’s immune system. The outcome was that the bacteria often did not respond successfully to the treatment and the soldier’s bodies would be considerably weakened, contributing to a large number of soldiers dying from their treatment instead of the original infection. Fleming’s conclusion was to assess the wounds for their severity and prioritise cleanliness of the wound; however his approach was not favoured.

Fleming devised an experiment which explained why the antiseptics were doing more harm than good, and submitted his findings to The Lancet journal. He explained that antiseptics tackled the problem only superficially but did not work for deep wounds infected with bacteria. Unfortunately, although Sir Almroth Wright supported his claims, the majority of medical officers continued to treat their patients using the traditional methods.

By 1918, the war was over and Fleming and his compatriots returned home. Fleming began work at St Mary’s Hospital and ten years later was elected as a Professor of the School and later worked as a Professor of Bacteriology at the University of London. Whilst his academic career continued to flourish, so did his experimentation and research skills. He continued to work on antibacterial substances, using tests on patients with bad colds to discover the inhibitory effects of mucus on bacterial growth. This practical study was the first recorded discovery of lysozyme which is an antibacterial enzyme found in tears and saliva, which can breakdown cell walls in some bacteria. He discovered lysozyme in 1921 and although it was only effective on some bacteria, it was still a noteworthy medical breakthrough.

Eight years later Fleming would make his most famous discovery, although in accidental, unplanned circumstances during his work on the influenza virus. In September 1928 Fleming returned to his laboratory after spending some time away in August with his family. On his return he found that mould had grown on a staphylococcus culture plate and formed a bacteria barrier around it. The bacteria immediately surrounding the fungus had been destroyed. Fleming’s discovery prompted further investigation, in which he observed that the mould culture prevented the growth of this bacteria, even when diluted. This powerful substance, which had previously been called “mould juice”, was identified as the genus Penicillium and by 1929 had been named penicillin and revolutionised medical science for all subsequent generations. The world’s first antibiotic had been discovered.

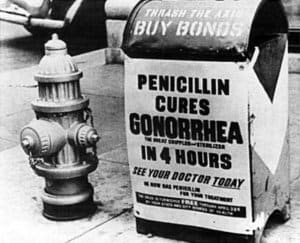

Further investigations would later show its powerful anti-bacterial effects on many hard-to-treat organisms such as the pathogens which caused pneumonia, meningitis, scarlet fever and also gonorrhea. Fleming would go on to publish his observations, however it would fail to gain much attention and after some setbacks in the mass production of penicillin, Fleming turned his attentions to other areas of work. It was Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain who would later have the funds and research to start mass production, just in time for the Second World War and the treatment of wounded soldiers.

In 1944 Alexander Fleming became Sir Alexander Fleming, an important acknowledgement for his scientific endeavours. Fleming’s career flourished and he served in various positions as President of the Society for General Microbiology and as Rector of Edinburgh University. By 1953, Sir Alexander Fleming had married again to a fellow doctor working for St Mary’s and lived a further two years, dying in March 1955.

His legacy changed the practice of medicine for future generations and saved countless lives. Sir Alexander Fleming’s career and discoveries shall be celebrated and acknowledged for a long time to come.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.