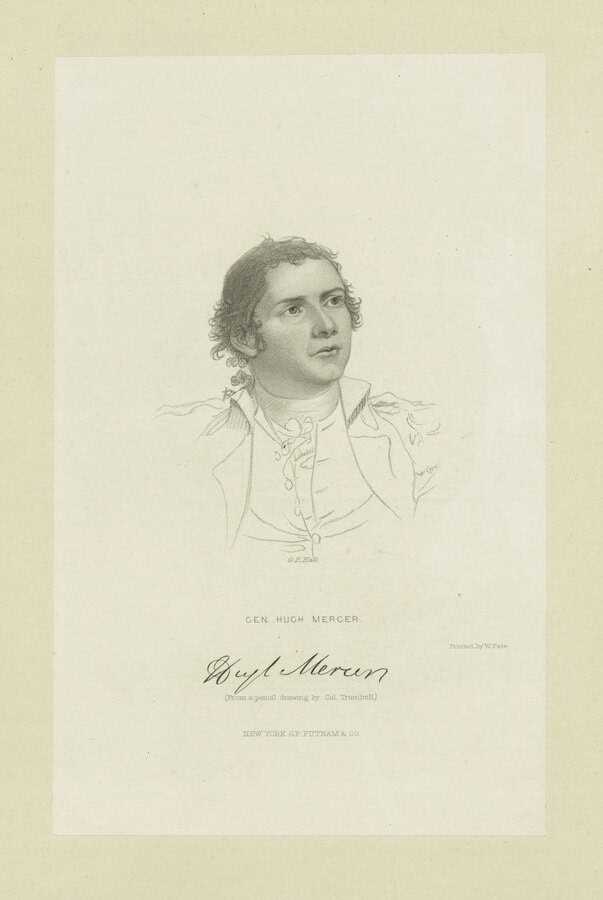

Hugh Mercer (1725-1777), a son of Pitsligo kirk minister William Mercer, of Rosehearty, was one of several Highlander Jacobites to leave behind “his own, his native land” in the eighteenth century after having faced British troops at Culloden — only to face them again years later in America. During his half-century lifetime, this minister’s son participated in three different military campaigns involving the Hanoverian Redcoats, one in his homeland and the other two in America.

In his initial war experience, in 1746, fate pitted him against the polished army of King George II, led by the Duke of Cumberland, Prince William, on the Drummossie Moor, near Inverness. At 21 years of age and contrary to his family’s wishes, Hugh joined the army of Prince Charles Edward Stuart in the latter’s attempt to restore his father to the throne.

Mercer’s family pleaded with him not to jeopardise the promising medical career for which he had just completed his studies. Nevertheless, the Highlander youth followed a different path. “Wha shall be King, but Charlie?”

Indeed, on the fateful morning of 16 April, Mercer received his baptism by fire while beholding the duke’s atrocities in the freezing cold and wet.

Thirty-one years later, similar circumstances took place on the fields of Princeton, New Jersey. There, (again) British soldiers surrounded Mercer, ever the independence- and freedom-minded Scot, and prepared to show him no quarter. Between those two menacing encounters, considerable adventure occurred in Mercer’s life to bring him ‘round full circle.

Early in 1747, during the Clearances, he took leave of his country from Edinburgh (Leith) onboard a ship bound for Philadelphia. When the ship docked in America, he did not dally in that port city but moved out to the edge of the Pennsylvania frontier, some 200 miles further inland, along the eastern edge of the Allegheny Mountains. There he hoped he could simply forget about Culloden.

But the relative peace in that heavily forested area did not last. Beginning in the mid-1750s, he found himself in the heart of the North American front in the Seven Years’ War. Seeing so many wounded, the doctor took compassion on his fellows and joined the Pennsylvania Associators, a militia comprising American settlers in support of Britain. His first recorded action as an Associator came in 1756, when he led a company of men in John Armstrong’s regiment in the raid on Kittanning, Pennsylvania. Armstrong was Scottish, and a Covenanter at that, who had emigrated to America a few years before Mercer had. The two of them bonded very quickly. It was Armstrong’s son 20 years into the future who would carry the mortally wounded Mercer off the battlefield at Princeton, New Jersey.

Hugh’s next mission, in 1758, was to accompany the army of Brig. Gen. John Forbes in what would be Britain’s third attempt to wrest control of Fort Duquesne from the French. Forbes was a fellow Scot whose ancestry, coincidentally, traced back to Pitsligo — to the very church that Mercer’s father and grandfather served. Lord Alexander Forbes built that church in 1634-1635.

Whether Forbes and Mercer realised their nearly-joined roots, the one led the other in cutting a new military road across the wilderness from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to the Forks of the Ohio. This time, the British reached the old fort. As the prepared to depart the area, he called on Hugh Mercer to remain behind after the army dispersed, to man the station until a permanent garrison could be established.

It was during the construction of Forbes’ Road that Mercer met another soldier named George Washington, and the two became fast friends. Following the completion of Mercer’s duty in Pennsylvania, he relocated to Fredericksburg, Virginia, at Washington’s urging. Fredericksburg was home to several Scots. There he opened another apothecary and continued practicing as a surgeon. Among his new clients was Madam Washington, the future President’s mother.

From 1761 to 1775, Mercer became ensconced in Fredericksburg society. He married, had children, and formed lasting associations with powerful, influential men allied with the patriot cause. Besides Washington, his list of friends and acquaintances included George Mason, James Monroe, John Marshall, George Weedon and John Paul Jones — quite a group.

Some years later, after the first shots were fired at Lexington, Massachusetts, in 1775, other colonies rallied to assist the patriots in Massachusetts. In Virginia, Hugh Mercer was elected a colonel of Minute Men of Spotsylvania, King George, Stafford, and Caroline counties.

At the time of his appointment, he pronounced to his electors, “Every man should be content to serve in that station in which he can be most useful. For my part, I have but one object in view, and that is, the success of the cause; and God can witness how cheerfully I would lay down my life to secure it”. They were, indeed, prophetic words.

In early 1776, Virginians organized three regiments to be part of the Continental Army, which Washington commanded. Mercer was elected colonel of the 3rd Virginia Regiment. Weedon served as his lieutenant-colonel and Thomas Marshall (father of future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall) was his major. When he left home, it was the last time that Col. Mercer saw his wife and children.

Initially, he commanded the Continental Army’s “Flying Camp Battalion,” a body of 10,000 men that were organised for rapid mobility across New Jersey, primarily. After the Continental Army’s retreat off Manhattan, Washington feared that the Brits would be able to relocate anywhere in a large area of the middle colonies. He therefore established the Flying Camp Battalion and put Mercer in charge.

Patriot sympathisers in New Jersey, many of whom were concentrated around Princeton, came to regard Hugh Mercer highly. Not only had he contributed to protecting New Jersey, but indeed he may have played an important role in saving the Patriot cause itself. Some sources indicate Mercer influenced Washington to cross the Delaware River on Christmas night of that year, a move which reversed the war’s momentum — and Washington’s image — following the many British victories in New York.

According to biographer John T. Goolrick in The Life of General Hugh Mercer (New York, 1906), “Major Armstrong (John Armstrong, Jr., Mercer’s aide-de-camp), who was present at a council of officers, and who was with Mercer at the crossing of the Delaware, is (the) authority for the statement that Mercer suggested this expedition…”

Both Mercer and Washington had previous experience crossing rivers at night. While Washington’s retreat off Long Island is well known, Mercer’s previous experience is lesser known. On 8 Feb 1760, before Mercer resigned from the Pennsylvania Associators, he and James Burd were leading a troop movement from Lancaster to Carlisle. To speed the trip, the two colonels decided to cross the icy Susquehanna River themselves that night, prior to their men crossing the next morning.

In his journal, Burd later wrote of that expedition, “I fell in the river twice and Colonel Mercer once.”

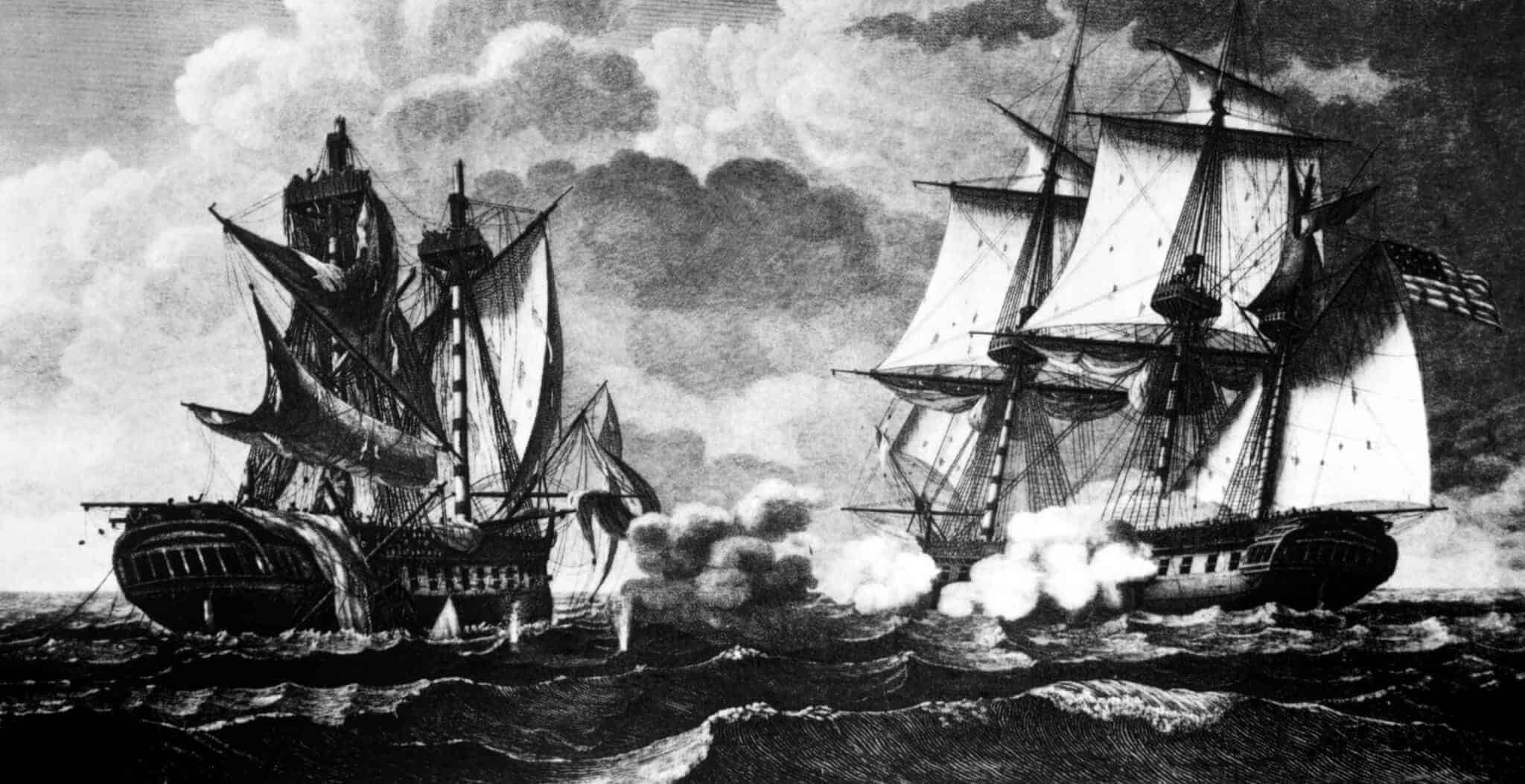

A week following the Patriot victory over Hessian auxiliaries at Trenton, New Jersey, Mercer led a detachment of 350 men to destroy a bridge over Stony Brook, along the principal Trenton-Princeton Road. British Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood spotted his men. Mawhood was, in turn, leading his own men to Trenton along that road. The two armies raced each other for better position before commencing hand-to-hand fighting. The Battle of Princeton, 3 Jan 1777, had begun.

Mercer brought his horse to the front of his line, trying to rally his fleeing men. In the chaos, a bullet shattered his mount’s foreleg and the animal went down. The veteran dismounted his steed, but the Hanoverians quickly surrounded him. They had, in fact, mistaken him for Washington.

They demanded he surrender, but the Highlander’s pride and love of freedom boiled his blood. He unsheathed his claymore and cursed at them in Gaelic (“Away n’ bile ye rheids”). Realising their mistake, but not knowing him from any other Scot, they beat him silly and stabbed him repeatedly.

In that one, brief moment, he must have felt a haunting sensation of déjà vu. Visions of Culloden must have rushed back to his mind as they repeatedly stabbed him and left him for dead.

Goolrick states that the 51-year-old veteran soldier “seems to have excited the brutality of the [Hanoverians] by the gallantry of his resistance… He was stabbed by their bayonets in seven different parts of the body, and they inflicted upon his head many blows with the butt-end of their muskets, only ceasing this butchery when they believed him dead”.

Hugh Mercer’s life, at its very end, had indeed come full circle. John Armstrong, Jr., the son of his good friend, carried the wounded general from the battlefield to a house nearby owned by a Quaker farmer. Nine days later, in the arms of Washington’s nephew George Lewis, Hugh Mercer drew his last breath.

Washington was said to have called him a “brave and worthy general”.

The author is an experienced writer, editor, and print journalist based in the United States. Mr Swafford has a bachelor of arts degree in journalism with other emphases in English and classical literature. Having considerable magazine writing experience, he has long enjoyed the study of history. For the past 15 years, he has specialized in writing about colonial and revolutionary America. He also edits the membership magazine of the General Society Sons of the Revolution, a major lineage society in the United States for descendants of patriot soldiers of the American Revolution.

Published: 17th March 2025.