This article presents the role John Knox’s leadership played in the success of the Scottish Protestant Reformation in 1560.

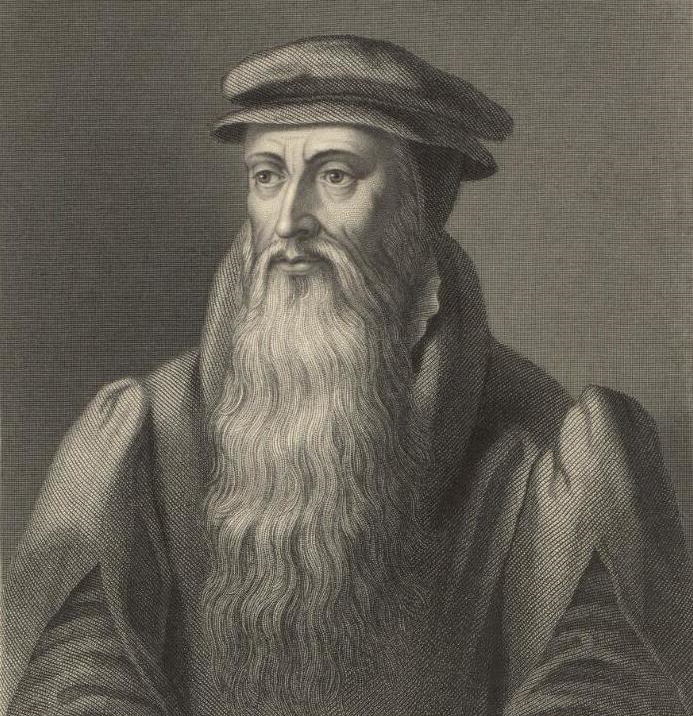

John Knox, born in approximately 1514 in Haddington, East Lothian, Scotland, is considered as one of the founders of the Scottish Reformation which was established in 1560. Knox’s unfortunate beginnings provided a catalyst for his ambitious revelations of reform and dedication to adapting the national beliefs of the Scottish realm.

What is known of Knox’s early life is limited but believed to be of humble origin, characterised by poverty and health issues, which undoubtedly provided a foundation for his struggle for change. Lloyd-Jones argues that Knox was “brought up in poverty, in a poor family, with no aristocratic antecedents, and no one to recommend him”. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that Knox chose to work to achieve a better status for himself and to use his passion for Protestantism to enhance his social position and to improve his financial situation.

The Scottish Realm at the time of Knox’s existence was under Stewart Dynasty and Catholic Church. Knox blamed the economic grievances amongst the poor upon those who had the political power to change the situation, most notably Marie de Guise, Regent of Scotland and on her return to Scotland in 1560, Queen Mary Stewart or as she is more popularly known, Mary Queen of Scots. These political grievances of Knox’s against those in charge, and his ambition to reform the National Church of Scotland saw a fight to establish the Reformed Protestant Church leading to a Protestant Reformation which would alter the governance and belief systems in Scotland.

In his early years, Knox experienced the loss of his peers Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart who were leaders in the Protestant cause. Both Hamilton and Wishart were executed for their considered “heretical beliefs” by the Scottish government, at that time Catholic. During the early sixteenth century Protestantism was a relatively new concept and not accepted widely in Early Modern Europe. The executions of Wishart and Hamilton stirred Knox and he used the ideas of martyrdom and persecution in his writings to act as criticisms against the Catholic institutions and to preach corruption in the Early Modern World.

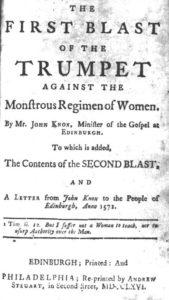

In Knox’s ‘The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women’ published in 1558, he demonstrated that the Scottish Kirk had been lead by corrupt and foreign leaders and that the country needed reform and change for its own advancement and religious morality:

“We se our countrie set furthe for a pray to foreine nations, we heare the blood of our brethren, the members of Christ Jesus most cruelly to be shed, and the monstrous empire of a cruell women (the secrete counsel of God excepted) we knowe to be the onlie occasion of all the miseries…The vigour of the persecution had struck all heart out of the Protestants.”

Knox’s language in this publication expresses the grievances of the Protestant Reformers against their Catholic rulers and their management of the religious and social divides that existed in the realm. It portrays a deep anger toward the lack of religious morality and lack of poor relief.

Knox spent time in England following his exile from Scotland and therefore was able to work on his Protestant Reform under the kingship of Edward VI, the young Tudor king.

Knox referred to the King as having a great wisdom despite being a minor, and that his dedication to the Protestant cause was invaluable to the people of England. Knox’s progression in England however was halted by Edward’s sudden death in 1554 and the succession of the Catholic Queen Mary Tudor. Knox argued that Mary Tudor had upset God’s will and that her presence as England’s Queen was a punishment for the lack of religious integrity of the people. He argued that God had;

“hot displeasure…as the acts of her unhappy reign can sufficiently witness.”

Mary Tudor’s succession in 1554 sparked the writings of Protestant Reformers such as Knox and the Englishman Thomas Becon against the corruption of the Catholic rulers in England and Scotland at this time, and used the nature of their sex also to merely undermine their authority and religious morality. In 1554, Becon remarked;

“Ah Lord! To take away the empire from a man and give it to a woman, seemeth to be an evident token of thine anger towards us Englishmen.”

Both Knox and Becon at this time can be seen to be angered by the stagnation of Protestant reforms due to the Catholic Queens Mary Tudor and Mary Stewart and their Catholic Regimes.

Knox did leave his mark on the English Church through his involvement in the English ‘Book of Common Prayer’, which was later adapted by Queen Elizabeth I of England in her restoration of the Protestant Church of England in 1558.

Later Knox spent time in Geneva under the reformer John Calvin and was able to learn from what Knox described as “the most perfect school of Christ.”

Geneva provided the perfect example to Knox how, with dedication a Protestant Reformation in a realm was possible and could flourish. Calvin’s Protestant Geneva provided Knox with the initiative to fight for a Scottish Protestant Reformation. With his return to Scotland in 1560 and with the aid this time of Protestant individuals such as James, Earl of Morray, half-brother to the Queen of Scots, the Protestant Reformation in Scotland could be a success.

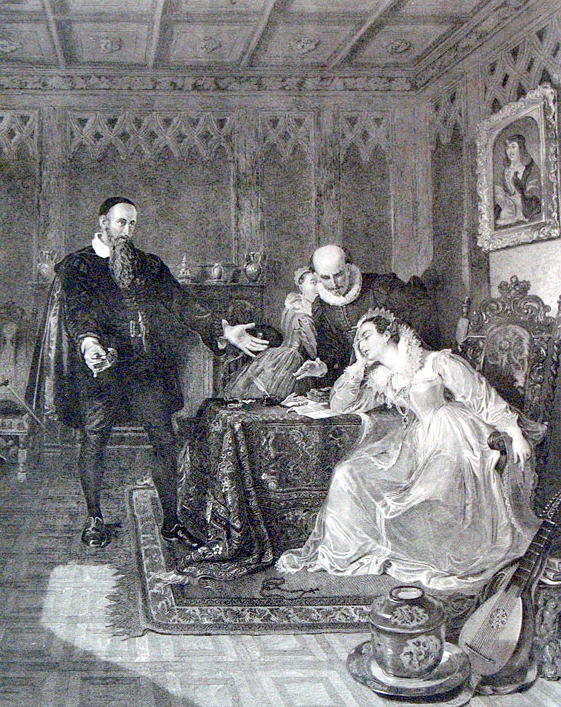

When Mary Queen of Scots returned to Scotland, it is commonly known that she and Knox were not the best of friends. Knox was anxious to push forward with the Protestant Reforms, whilst Mary was a hinderance to this as she was strictly Catholic and despised Knox’s actions that attacked her authority and her beliefs. Although Mary remained Scotland’s Queen, the power of the Scottish Protestants was ever-growing and in 1567, Mary lost her fight for her crown and was sent to England under house arrest.

The Scottish Protestants had control now and Protestantism became the religion of the realm. By this time the protestant Elizabeth I was ruling England and had Mary Stewart under her control.

Whilst by the time of Knox’s death in 1572, the Protestant Reformation was by no means complete, Scotland by this time was being ruled by a Scottish Protestant King, James VI the son of Mary Queen of Scots. He would also inherit the crown of England to become King James I of England and unite both countries under Protestantism.

Knox’s writings and his determination to fight for Scotland to be Protestant saw the Scottish nation and its identity changed forever. Today Scotland’s national religion remains Protestant in nature and therefore, demonstrates that the Scottish Reformation Knox started in 1560 was a success and longstanding.

Written by Leah Rhiannon Savage aged 22, Master’s Graduate of History from Nottingham Trent University. Specialises in British History and predominantly Scottish History. Wife and Aspiring Teacher of History. Writer of Dissertations on John Knox and the Scottish Reformation and The Social Experiences of The Bruce Family during The Scottish Wars of Independence (1296-1314).