Joseph Knight was born in Africa, captured and enslaved in his youth and sent to the Caribbean, but he ended his life in Scotland, a free man.

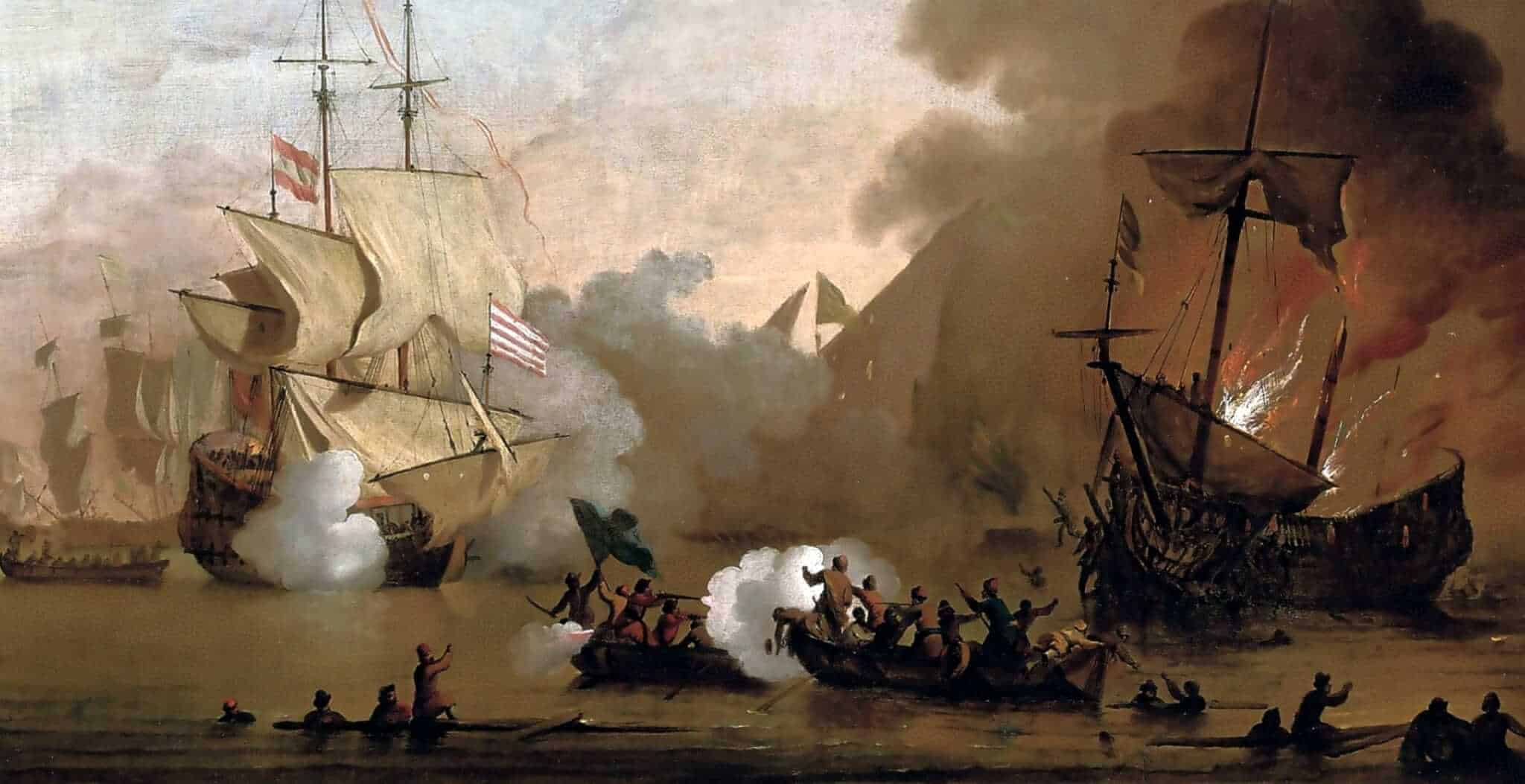

Although records are unclear, Knight believed that his country of birth was Guinea. What is known, however, is that he was transported from Africa to Jamaica, between the ages of around eight and twelve years old. Then, in the slave market in Jamaica, he was bought by a Scot, John Wedderburn the 6th Baronet of Blackness, to be a slave on his sugar plantation.

Perhaps unusually, Wedderburn trained Knight as a household slave, and did not have him working in the plantation fields. During his time with Wedderburn in Jamaica, Knight became literate and was a valuable member of the Wedderburn household.

Wedderburn had originally travelled to Jamaica to seek his fortune because his family lands had been stripped from them after the battle of Culloden. His father, also John Wedderburn, the 5th Baronet of Blackness, had been a staunch Jacobite who had fought for Bonnie Prince Charlie at the Battle of Culloden in 1745. He somehow survived the massacre, only to be captured and subsequently executed.

To be a Jacobite was considered treason by the British government at the time, so as well as hanging, drawing and quartering the unfortunate elder Wedderburn, the Wedderburns’ family lands and titles were stripped from them. Because of this, Wedderburn’s son, finding himself without home, money, or prospects, emigrated to Jamaica to seek his fortune. He found a ship sailing from Glasgow that would allow him to work onboard to pay for his passage to the Caribbean. He arrived in Jamaica in 1747.

In the eighteenth century, the British were the largest exporters of sugar in the world, and by 1800 Scotland owned around thirty percent of the sugar plantations on Jamaica. Wedderburn himself had owned as much as ten percent of the entire landmass of Jamaica at one time. He purchased a sugar plantation on his arrival in 1747 and within twenty years had become one of the biggest and most successful landowners on the island.

Once Wedderburn had made a sufficient fortune in the colonies, he returned to Scotland in 1769 to reclaim his family land and title, taking Joseph Knight, with him. Upon returning to Scotland Wedderburn purchased the Ballindean estate in Perthshire, where Ballindean house, an 1832 rebuild of the original, still stands today. Joseph Knight continued to live and work in the Wedderburn household where he fell in love with a local servant girl called Annie Thomson. Annie and Knight married and later Annie became pregnant and Knight wanted to leave the Wedderburn household to set up his own home with his wife and child. Wedderburn refused him and Knight was subsequently arrested. This catalysed a legal battle that would last for four years and result in the abolition of personal slavery within Scotland in 1778.

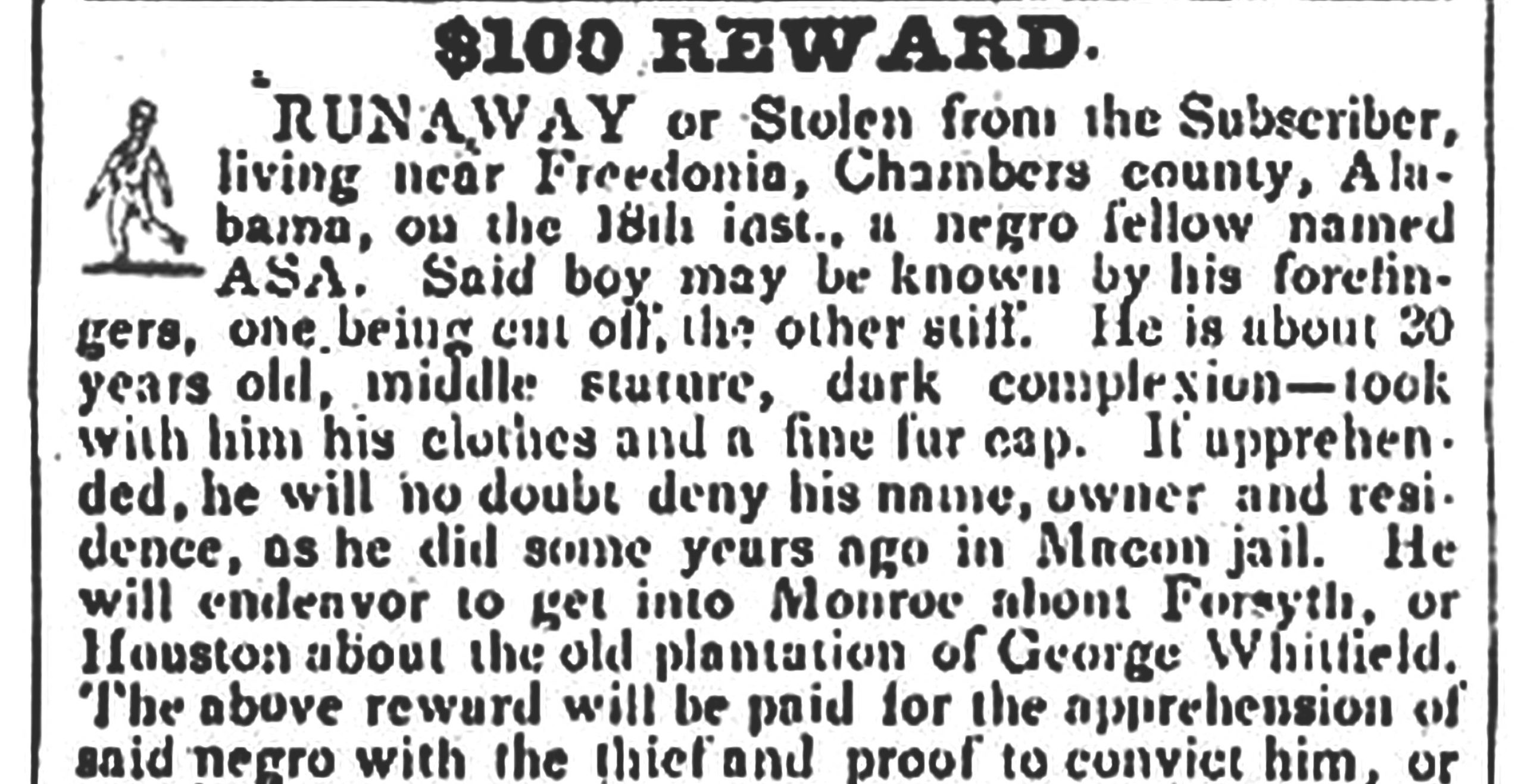

The first legal challenge of the Knight vs. Wedderburn case began in 1774, in the Justice of the Peace Court in Perth. Knight argued, that because there was no slavery within Scotland itself, that although he may had been ‘legally bought’ in Jamaica, when he had arrived in Scotland he had automatically become free. The justices disagreed however, and found in favour of Wedderburn.

Knight appealed the decision in the Perth Sherriff Court and won, with the ruling that –

“the state of slavery is not recognised by the laws of this kingdom, and is inconsistent with the principles thereof: That the regulations in Jamaica, concerning slaves, do not extend to this kingdom.”

Wedderburn then subsequently appealed this decision, and took the argument to the highest court in Scotland, the Court of Session, Scotland’s Supreme Court in Edinburgh. He argued that Knight was not his slave, but his ‘perpetual servant’.

This was a state that existed within Scottish law, and therefore Knight should be returned to his household to work for him in perpetuity. Knight of course, disagreed. There are many other historical instances of similar definitions, distinctions and legal loopholes being used to keep people in servitude in Scotland, such as the colliers and salters in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In the final appeal of 1778, at the supreme court in Edinburgh, twelve judges sat on the panel that were to decide Knight’s case, and declare him free, or not. Thankfully, of the twelve, eight found in favour of Knight, with only four against. They argued that the law keeping Knight in slavery was unjust and could not be supported in Scotland.

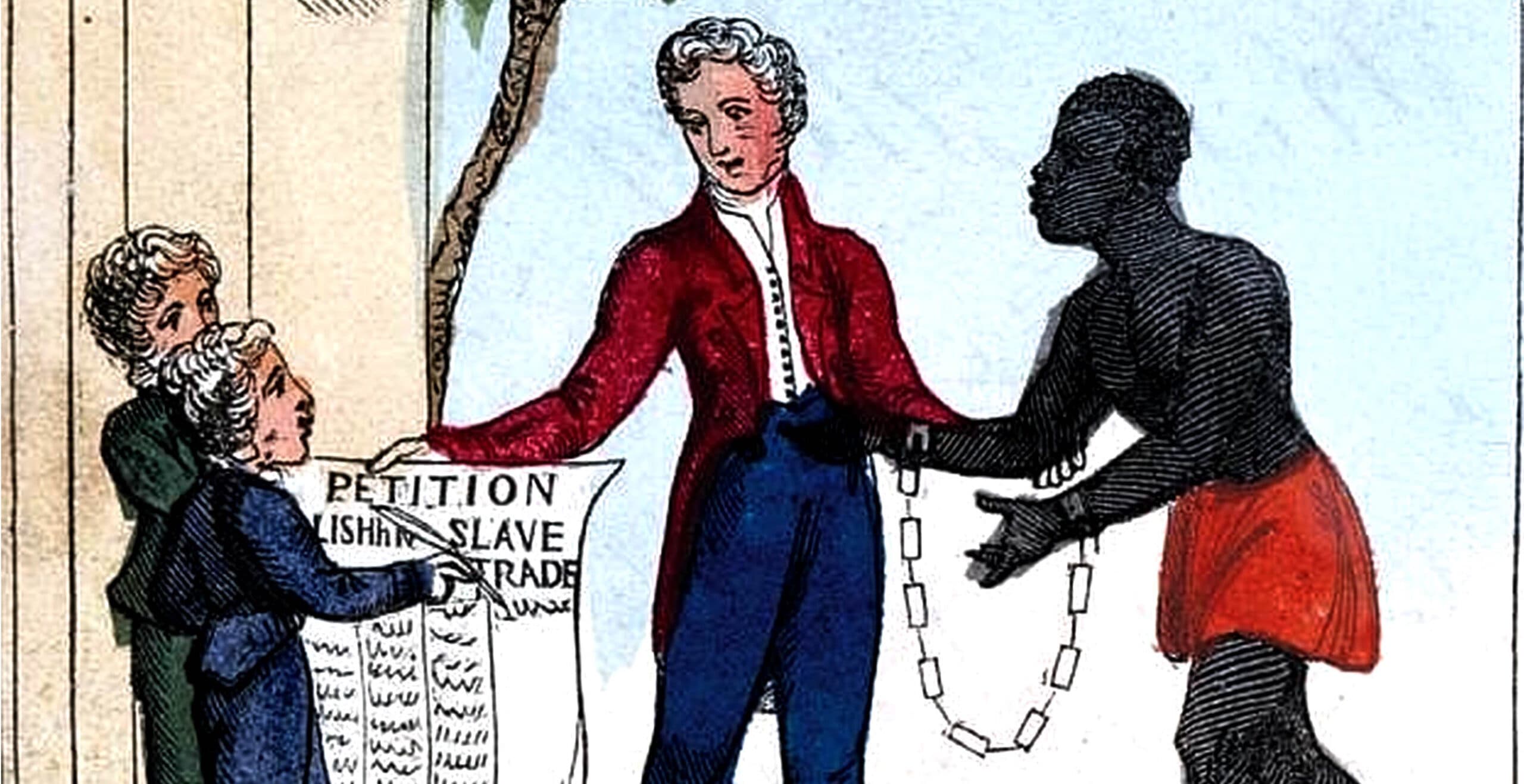

Knight had won his freedom after a gruelling four-year fight. This ruling essentially led to the abolition of personal slavery in Scotland, however it wasn’t until 1807 that the slave trade was abolished, and as late as 1838 when the slaves in the colonies were finally freed.

After Knight won his freedom, he and Annie disappeared from history, one can only hope, to live out their lives happily together in their own home. Even the exact date of Knight’s death is unknown, although the assumption is that he lived out his life in Scotland.

So compelling is the story of Joseph Knight and his fight for freedom, that Glasgow based playwright, May Sumbwanyambe has written a new play based on his life.

Knight’s Controversial Lawyer

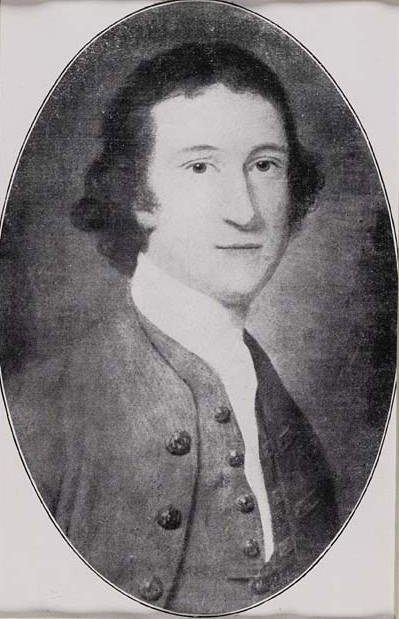

Somewhat ironically, the lawyer that defended Knight’s right to freedom during the court battles was Henry Dundas, the 1st Viscount Melville. Some argue that Dundas, through his deliberate delay of the abolition movement, was personally responsible for the enslavement of an additional half a million people. However, other historians, such as Tom Devine, argue that Dundas was actually a supporter of gradual abolition and was not himself individually responsible for the delay to the abolition of the slave trade. The debate as to how responsible the man actually was to the abolition movement is still raging amongst historians today. What is known though, is that it was this controversial figure who fought for Knight’s freedom.

A contentious statue commemorating Henry Dundas still stands in St. Andrew’s square in Edinburgh today. Although the wording of the commemorative plaque was changed in 2020 to read –

“Dundas was a contentious figure, provoking controversies that resonate to this day. While Home Secretary in 1792 and first Secretary of State for War in 1796 he was instrumental in deferring the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. Slave trading by British ships was not abolished until 1807. As a result of this delay, more than half a million enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic.”

What makes his statue even more interesting, is that it stands upon a plinth that was supposedly modelled on Trajan’s column, and is so high that Robert Stevenson, a famous civil engineer and lighthouse builder who was also grandfather of Robert-Louis Stevenson, was brought in to consult on the column. Clearly the construction was sound, as it has stood fast for over two hundred years.

By Terry MacEwen, Freelance Writer.

Published: 14th September 2022.