Kings and Queens of Scotland from 1005 to the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James VI succeeded to the throne of England.

Celtic kings from the unification of Scotland

1005: Malcolm II (Mael Coluim II). He acquired the throne by killing Kenneth III (Cinaed III) of a rival royal dynasty. Attempted to expand his kingdom southwards with a notable victory at the Battle of Carham, Northumbria in 1018. He was driven north again in 1027 by Canute (Cnut the Great) the Dane, the Danish king of England. Malcolm died on 25th November 1034, according to one account of the time he was “killed fighting bandits”. Leaving no sons he named his grandson Duncan I, as his successor.

1005: Malcolm II (Mael Coluim II). He acquired the throne by killing Kenneth III (Cinaed III) of a rival royal dynasty. Attempted to expand his kingdom southwards with a notable victory at the Battle of Carham, Northumbria in 1018. He was driven north again in 1027 by Canute (Cnut the Great) the Dane, the Danish king of England. Malcolm died on 25th November 1034, according to one account of the time he was “killed fighting bandits”. Leaving no sons he named his grandson Duncan I, as his successor.

1034: Duncan I (Donnchad I). Succeeded his grandfather Malcolm II as King of the Scots. Invaded northern England and besieged Durham in 1039, but was met with a disastrous defeat. Duncan was killed during, or after, a battle at Bothganowan, near Elgin, on 15th August, 1040.

1040: Macbeth. Acquired the throne after defeating Duncan I in battle following years of family feuding. He was the first Scottish king to make a pilgrimage to Rome. A generous patron of the church it is thought he was buried at Iona, the traditional resting place of the kings of the Scots.

1057: Malcolm III Canmore (Mael Coluim III Cenn Mór). Succeeded to the throne after killing Macbeth and Macbeth’s stepson Lulach in an English-sponsored attack. William I (The Conqueror) invaded Scotland in 1072 and forced Malcolm to accept the Peace of Abernethy and become his vassal.

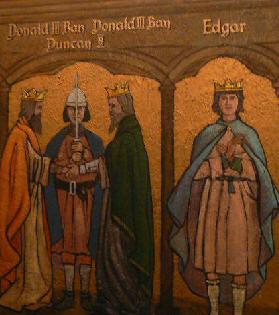

1093: Donald III Ban. Son of Duncan I he seized the throne from his brother Malcolm III and made the Anglo-Normans very unwelcome at his court. He was defeated and dethroned by his nephew Duncan II in May 1094

1094: Duncan II. Son of Malcolm III. In 1072 he had been sent to the court of William I as a hostage. With the help of an army supplied by William II (Rufus) he defeated his uncle Donald III Ban. His foreign supporters were detested. Donald engineered his murder on 12 November 1094.

1094: Donald III Ban (restored). In 1097 Donald was captured and blinded by another of his nephews, Edgar. A true Scottish nationalist, it is perhaps fitting that this would be the last king of the Scots who would be laid to rest by the Gaelic Monks at Iona.

1097: Edgar. Eldest son of Malcolm III. He had taken refuge in England when his parents died in 1093. Following the death of his half-brother Duncan II, he became the Anglo-Norman candidate for the Scottish throne. He defeated Donald III Ban with the aid of an army supplied by William II. Unmarried, he was buried at Dunfermline Priory in Fife. His sister married Henry I in 1100.

1107: Alexander I. The son of Malcolm III and his English wife St. Margaret. Succeeded his brother Edgar to the throne and continued the policy of ‘reforming’ the Scottish Church, building his new priory at Scone near Perth. He married the illegitimate daughter of Henry I. He died childless and was buried in Dunfermline.

1107: Alexander I. The son of Malcolm III and his English wife St. Margaret. Succeeded his brother Edgar to the throne and continued the policy of ‘reforming’ the Scottish Church, building his new priory at Scone near Perth. He married the illegitimate daughter of Henry I. He died childless and was buried in Dunfermline.

1124: David I. The youngest son of Malcolm III and St. Margaret. A modernising king, responsible for transforming his kingdom largely by continuing the work of Anglicisation begun by his mother. He seems to have spent as much time in England as he did in Scotland. He was the first Scottish king to issue his own coins and he promoted the development of towns at Edinburgh, Dunfermline, Perth, Stirling, Inverness and Aberdeen. By the end of his reign his lands extended over Newcastle and Carlisle. He was almost as rich and powerful as the king of England, and had attained an almost mythical status through a ‘Davidian’ revolution.

1153: Malcolm IV (Mael Coluim IV). Son of Henry of Northumbria. His grandfather David I persuaded the Scottish Chiefs to recognise Malcolm as his heir to the throne, and aged 12 he became king. Recognising ‘that the King of England had a better argument by reason of his much greater power’, Malcolm surrendered Cumbria and Northumbria to Henry II. He died unmarried and with reputation for chastity, hence his nickname ‘the Maiden’.

1153: Malcolm IV (Mael Coluim IV). Son of Henry of Northumbria. His grandfather David I persuaded the Scottish Chiefs to recognise Malcolm as his heir to the throne, and aged 12 he became king. Recognising ‘that the King of England had a better argument by reason of his much greater power’, Malcolm surrendered Cumbria and Northumbria to Henry II. He died unmarried and with reputation for chastity, hence his nickname ‘the Maiden’.

1165: William the Lion. Second son of Henry of Northumbria. After a failed attempt to invade Northumbria, William was captured by Henry II. In return for his release, William and other Scottish nobles had to swear allegiance to Henry and hand over sons as hostages. English garrisons were installed throughout Scotland. It was only in 1189 that William was able to recover Scottish independence in return for a payment of 10,000 marks. William’s reign witnessed the extension of royal authority northwards across the Moray Firth.

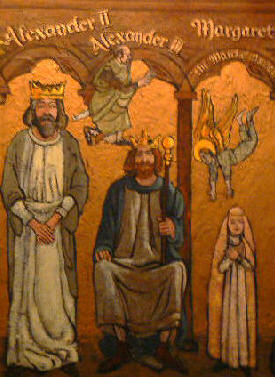

1214: Alexander II. Son of William the Lion. With the Anglo-Scottish agreement of 1217, he established a peace between the two kingdoms that would last for 80 years. The agreement was further cemented by his marriage to Henry III’s sister Joan in 1221. Renouncing his ancestral claim to Northumbria, the Anglo-Scottish border was finally established by the Tweed-Solway line.

1249: Alexander III. The son of Alexander II, he married Henry III’s daughter Margaret in 1251. Following the Battle of Largs against King Haakon of Norway in Oct. 1263, Alexander secured the western Highlands and Islands for the Scottish Crown. After the deaths of his sons, Alexander gained acceptance that his granddaughter Margaret should succeed him. He fell and was killed whilst riding along the cliffs of Kinghorn in Fife.

1286 – 90: Margaret, Maid of Norway. The only child of King Eric of Norway and Margaret, daughter of Alexander III. She became queen at the age of two, and was promptly betrothed to Edward, son of Edward I. She saw neither kingdom nor husband as she died aged 7 at Kirkwall on Orkney in September 1290. Her death caused the most serious crisis in Anglo-Scottish relations.

English domination

1292 – 96: John Balliol. Following the death of Margaret in 1290 no one person held the undisputed claim to be King of the Scots. No fewer than 13 ‘competitors’, or claimants eventually emerged. They agreed to recognise Edward I’s overlordship and to abide by his arbitration. Edward decided in favour of Balliol, who did have a strong claim with links back to William the Lion. Edward’s obvious manipulation of Balliol led the Scottish nobles to set up a Council of 12 in July 1295, as well as agreeing to an alliance with the King of France. Edward invaded, and after defeating Balliol at the Battle of Dunbar imprisoned him in the Tower of London. Balliol was eventually released into papal custody and ended his life in France.

1292 – 96: John Balliol. Following the death of Margaret in 1290 no one person held the undisputed claim to be King of the Scots. No fewer than 13 ‘competitors’, or claimants eventually emerged. They agreed to recognise Edward I’s overlordship and to abide by his arbitration. Edward decided in favour of Balliol, who did have a strong claim with links back to William the Lion. Edward’s obvious manipulation of Balliol led the Scottish nobles to set up a Council of 12 in July 1295, as well as agreeing to an alliance with the King of France. Edward invaded, and after defeating Balliol at the Battle of Dunbar imprisoned him in the Tower of London. Balliol was eventually released into papal custody and ended his life in France.

1296 -1306: annexed to England

House of Bruce

1306: Robert I the Bruce. In 1306 at Greyfriars Church Dumfries, he murdered his only possible rival for the throne, John Comyn. He was excommunicated for this sacrilege, but was still crowned King of the Scots just a few months later.

Robert was defeated in his first two battles against the English and became a fugitive, hunted by both Comyn’s friends and the English. Whilst hiding in a room he is said to have watched a spider swing from one rafter to another, in an attempt to anchor its web. It failed six times, but at the seventh attempt, succeeded. Bruce took this to be an omen and resolved to struggle on. His decisive victory over Edward II‘s army at Bannockburn in 1314 finally won the freedom he had struggled for.

1329: David II. The only surviving legitimate son of Robert Bruce, he succeeded his father when only 5 years of age. He was the first Scottish king to be crowned and anointed. Whether he would be able to keep the crown was another matter, faced with the combined hostilities of John Balliol and the ‘Disinherited’, those Scottish landowners that Robert Bruce had disinherited following his victory at Bannockburn. David was for a while even sent to France for his own safe keeping. In support of his allegiance with France he invaded England in 1346, whilst Edward III was otherwise occupied with the siege of Calais. His army was intercepted by forces raised by the Archbishop of York. David was wounded and captured. He was later released after agreeing to pay a ransom of 1000,000 marks. David died unexpectedly and without an heir, while trying to divorce his second wife in order to marry his latest mistress.

House of Stuart (Stewart)

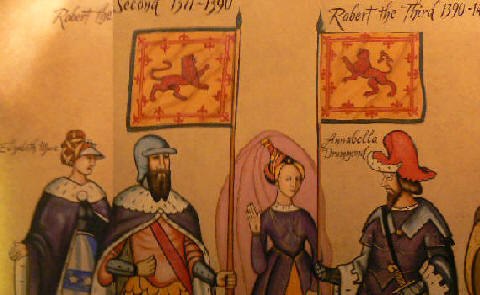

1371: Robert II. The son of Walter the Steward and Marjory, daughter of Robert Bruce. He was recognised the heir presumptive in 1318, but the birth of David II meant that he had to wait 50 years before he could become the first Stewart king at the age of 55. A poor and ineffective ruler with little interest in soldiering, he delegated responsibility for law and order to his sons. Meanwhile he resumed to his duties of producing heirs, fathering at least 21 children.

1390: Robert III. Upon succeeding to the throne he decided to take the name Robert rather than his given name John. As King, Robert III appears to have been as ineffective as his father Robert II. In 1406 he decided to send his eldest surviving son to France; the boy was captured by the English and imprisoned in the Tower. Robert died the following month and, according to one source, asked to be buried in a midden (dunghill) as ‘the worst of kings and most wretched of men’.

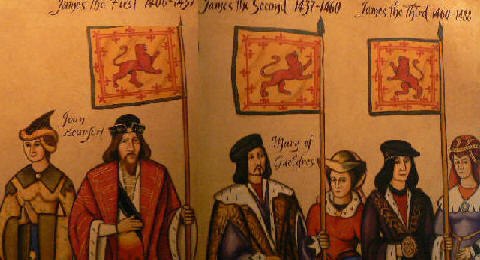

1406: James I. After falling into English hands on his way to France in 1406, James was held a captive until 1424. Apparently his uncle, who also just happened to be Scotland’s governor, did little to negotiate his release. He was eventually released after agreeing to pay a 50,000 mark ransom. On his return to Scotland, he spent much of his time raising the money to pay off his ransom by imposing taxes, confiscating estates from nobles and clan chiefs. Needless to say, such actions made him few friends; a group of conspirators broke into his bedchamber and murdered him.

1437: James II. Although king since the murder of his father when he was 7, it was following his marriage to Mary of Guelders that he actually assumed control. An aggressive and warlike king, he appears to have taken particular exception to the Livingstons and Black Douglases. Fascinated by those new fangled firearms, he was blown up and killed by one of his own siege guns whilst besieging Roxburgh.

1460: James III. At the tender age of 8, he was proclaimed king following the death of his father James II. Six years later he was kidnapped; upon his return to power, he proclaimed his abductors, the Boyds, traitors. His attempt to make peace with the English by marrying his sister off to an English noble was somewhat scuppered when she was found to be already pregnant. He was killed at the Battle of Sauchieburn in Stirlingshire on 11 June 1488.

ADVERTISEMENT

1488: James IV. The son of James III and Margaret of Denmark, he had grown up in the care of his mother at Stirling Castle. For his part in his father’s murder by the Scottish nobility at the Battle of Sauchieburn, he wore an iron belt next to skin as penitence for the rest of his life. To protect his borders he spent lavish sums on artillery and his navy. James led expeditions into the Highlands to assert royal authority and developed Edinburgh as his royal capital. He sought peace with England by marrying Henry VII’s daughter Margaret Tudor in 1503, an act that would ultimately unite the two kingdoms a century later. His immediate relationship with his brother-in-law deteriorated however when James invaded Northumberland. James was defeated and killed at Flodden, along with most of the leaders of Scottish society.

1513: James V. Still an infant at the time of his father’s death at Flodden, James’s early years were dominated by struggles between his English mother, Margaret Tudor and the Scottish nobles. Although king in name, James did not really start to gain control and rule the country until 1528. After that he slowly began to rebuild the shattered finances of the Crown, largely enriching the funds of the monarchy at the expense of the Church. Anglo-Scottish relationships once again descended into war when James failed to turn up for a scheduled meeting with Henry VIII at York in 1542. James apparently died of a nervous breakdown after hearing of the defeat of his forces following the Battle of Solway Moss.

1542: Mary Queen of Scots. Born just a week before her father King James V died. Mary was sent to France in 1548 to marry the Dauphin, the young French prince, in order to secure a Catholic alliance against England. In 1561, after he died still in his teens, Mary returned to Scotland. At this time Scotland was in the throes of the Reformation and a widening Protestant-Catholic split. A Protestant husband for Mary seemed the best chance for stability. Mary married her cousin Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, but it was not a success. Darnley became jealous of Mary’s secretary and favourite, David Riccio. He, together with others, murdered Riccio in front of Mary. She was six months pregnant at the time.

1542: Mary Queen of Scots. Born just a week before her father King James V died. Mary was sent to France in 1548 to marry the Dauphin, the young French prince, in order to secure a Catholic alliance against England. In 1561, after he died still in his teens, Mary returned to Scotland. At this time Scotland was in the throes of the Reformation and a widening Protestant-Catholic split. A Protestant husband for Mary seemed the best chance for stability. Mary married her cousin Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, but it was not a success. Darnley became jealous of Mary’s secretary and favourite, David Riccio. He, together with others, murdered Riccio in front of Mary. She was six months pregnant at the time.

Her son, the future King James VI, was baptised into the Catholic faith at Stirling Castle. This caused alarm amongst the Protestants. Darnley later died in mysterious circumstances. Mary sought comfort in James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, and rumours abounded that she was pregnant by him. Mary and Bothwell married. The Lords of Congregation did not approve of the liaison and she was imprisoned in Leven Castle. Mary eventually escaped and fled to England. In Protestant England, Catholic Mary’s arrival provoked a political crisis for Queen Elizabeth I. After 19 years of imprisonment in various castles throughout England, Mary was found guilty of treason for plotting against Elizabeth and was beheaded at Fotheringhay.

1567: James VI and I. Became king aged just 13 months following the abdication of his mother. By his late teens he was already beginning to demonstrate political intelligence and diplomacy in order to control government.

1567: James VI and I. Became king aged just 13 months following the abdication of his mother. By his late teens he was already beginning to demonstrate political intelligence and diplomacy in order to control government.

He assumed real power in 1583, and quickly established a strong centralised authority. He married Anne of Denmark in 1589.

As the great-grandson of Margaret Tudor, he succeeded to the English throne when Elizabeth I died in 1603, thus ending the centuries-old Anglo-Scots border wars.

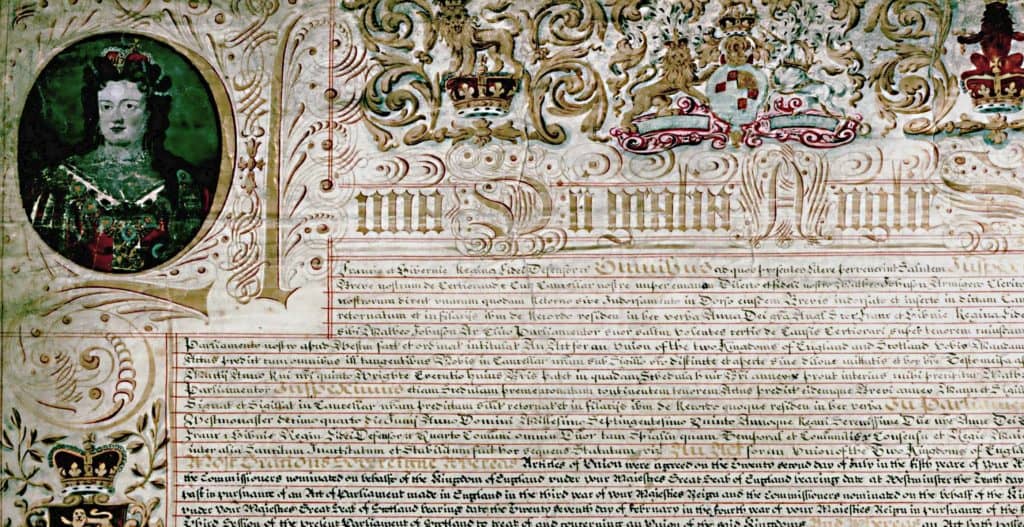

1603: Union of the crowns of Scotland and England.