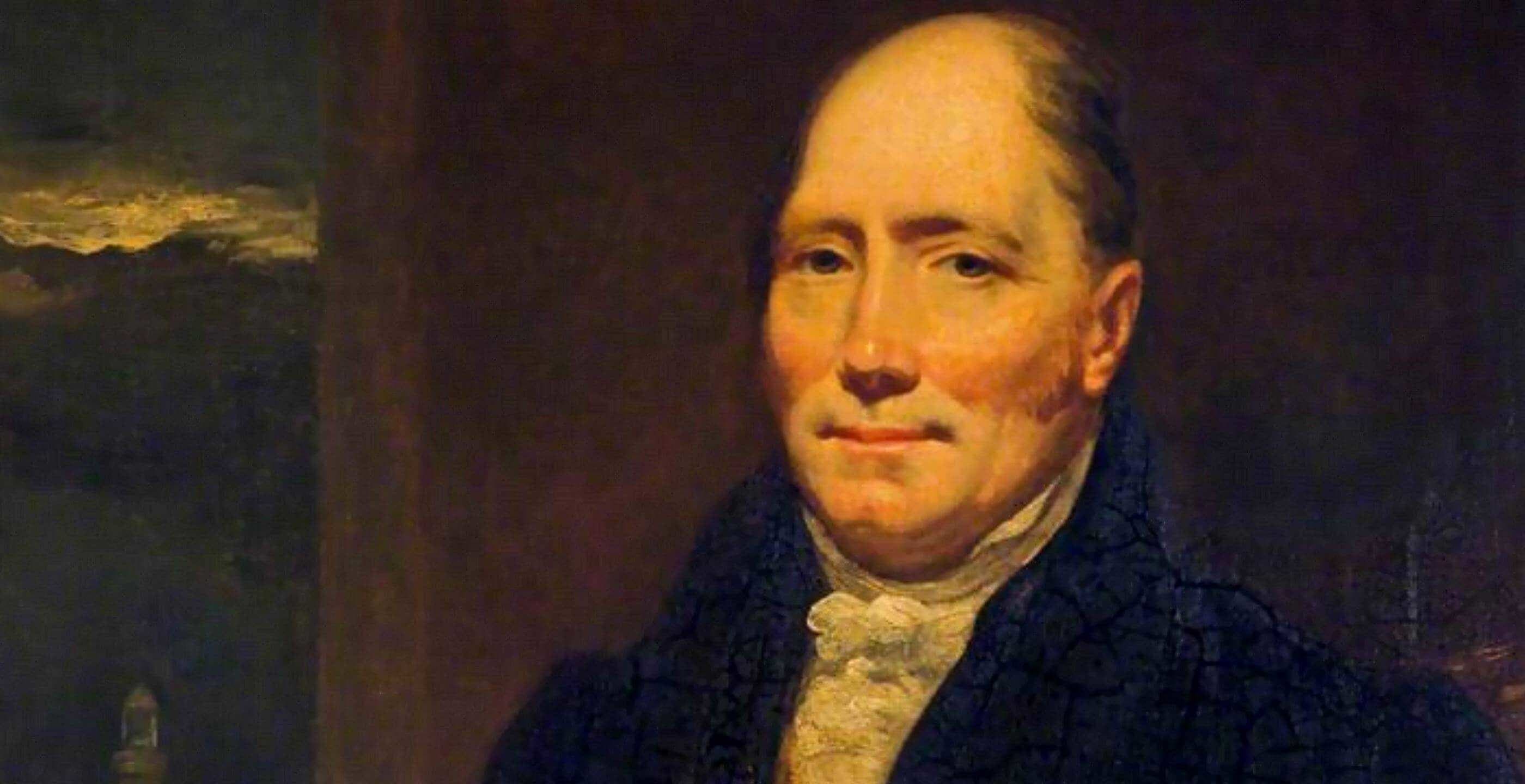

Until the early 1800’s a highly lucrative business had established itself along the dark and dim Scottish coastline. Some folk had grown rich from the resulting spoil of the wrecked ships that had come to grief on the rocks that lay hidden just beneath waves. Over the centuries, hundreds of ships and thousands of lives had been claimed by the treacherous reefs that surround the shores of Scotland. One man perhaps more than any other, can be credited with bringing an end to this grim trade – his name was Robert Stevenson.

Robert Stevenson was born in Glasgow on 8th June 1772. Robert’s father Alan and his brother Hugh ran a trading company from the city dealing in goods from the West Indies, and it was on a trip to the island of St Kitts that the brothers met their early end, when they contracted and died from a fever.

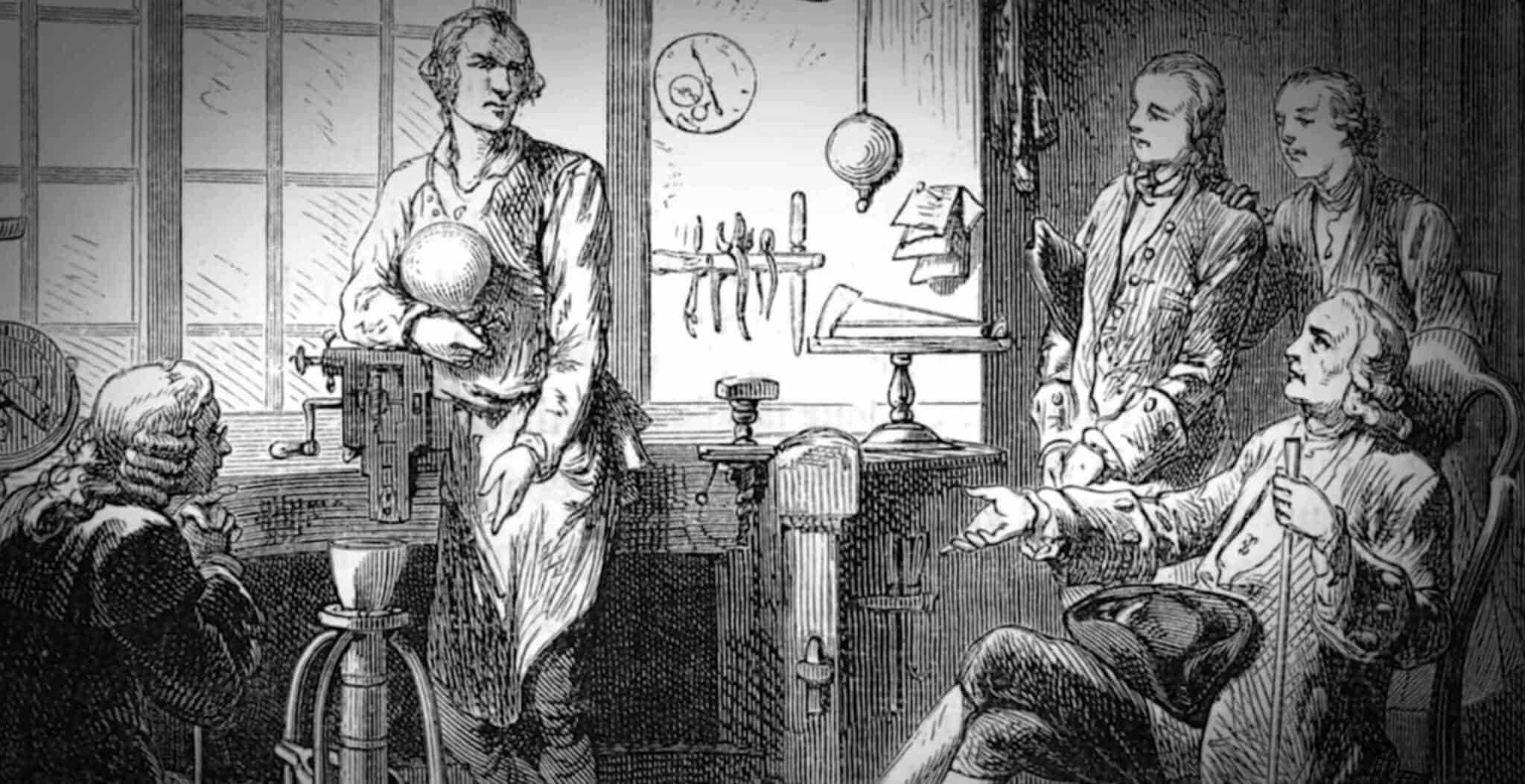

Without a regular income, Robert’s mother was left to bring up young Robert as best she could. Robert received his early education at a charity school before the family moved to Edinburgh where he was enrolled at the High School. A deeply religious person, it was through her church work that Robert’s mother met, and later married, Thomas Smith. A talented and ingenious mechanic, Thomas had recently been appointed engineer to the newly formed Northern Lighthouse Board.

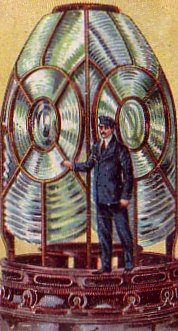

Throughout his latter teenage years Robert quite literally served his apprenticeship as assistant to his stepfather. Together they worked to supervise and improve the handful of crude coal-fired lighthouses that existed at that time, introducing innovations such as lamps and reflectors.

Lighthouse lantern using reflectors and huge ‘hyperradiant’ lanterns lit by incandescent petroleum vapour, early 1800s

Robert worked hard, and so impressed, that at the tender age of just 19 he was left to supervise the construction of his first lighthouse on the island of Little Cumbrae in the River Clyde. Perhaps recognising his lack of a more formal education, Robert also began to attend lectures in mathematics and science at the Andersonian Institute (now University of Strathclyde) in Glasgow.

Seasonal by its very nature, Robert successfully combined his practical summer work of constructing lighthouses in the Orkney Islands, whilst devoting the winter months to academic study at Edinburgh University.

In 1797 Robert was appointed engineer to the Lighthouse Board and two years later married his stepsister Jean, Thomas Smith’s eldest daughter by an earlier marriage.

One hazard in particular lay off Scotland’s east coast, near Dundee and the entrance to the Firth of Tay. This had claimed thousands of lives, with countless ships wrecked on its treacherous sandstone reef. Legend has it that Bell Rock earned its name from when a 14th century abbot from nearby Arbroath Abbey installed a warning bell on it. What is known however, is that an average of six ships were being wrecked every winter on those rocks and in one storm alone, 70 ships were lost along that stretch of coast.

Bell Rock Lighthouse

Robert had proposed the construction of a lighthouse on Bell Rock as early as 1799, however the costs and sheer scale of the project had frightened the other members of the Northern Lighthouse Board. In their eyes Robert was proposing the impossible. It would however take the wrecking of just one more vessel for the Board to reconsider Robert’s plan. It was the loss of the huge 64-gun warship HMS York and all of its 491 crew that changed things!

Although he had never built a lighthouse before, Britain’s most eminent engineer of the day John Rennie was given the job of chief engineer, with Robert as his resident on-site engineer. Together they agreed that John Smeaton’s ground-breaking Eddystone Lighthouse design would act as the model for their design.

With Rennie back in his London offices, it was Robert who was left with the day to day hardships of organising and building the lighthouse. And so on 17th August 1807, Robert and 35 workers set sail for the rock. Work was slow and laborious; using simple pickaxes the men could only work for two hours either side of each low tide, and then only during the calmer summer months. In between their shifts they rested on a ship moored a mile away. In the two years that followed they completed three courses of stonework and the mighty lighthouse stood just six feet tall!

The year of 1810 started badly for Robert, losing first his twins and then his youngest daughter to whooping cough. His lighthouse however was nearing completion, and was now attracting many tourists anxious to gaze upon the world’s tallest off-shore lighthouse. The 24 great lanterns that topped the granite stone structure were lit for the first time on 1st February 1811 …one of the Seven Wonders of the Industrial World.

Corsewall Lighthouse, built by Stevenson and now a hotel

In his fifty-year career as engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board, Robert went on to design and construct more than a dozen more lighthouses around the shores of Scotland and the surrounding islands. Innovating and inventing as he went, his civil engineering skills were always in much demand, including ventures into other areas such as bridges, canals, harbours, railways and roads.

The masterpiece of Robert’s career however will always be the Bell Rock Lighthouse, and whilst many still debate Rennie’s role in the project, the folk at the Northern Lighthouse Board appear clear where the praise should go. On Robert’s death in 1850, the following minute was read out at the Board’s Annual GM:

“The Board, before proceeding to business, desire to record their regret at the death of this zealous, faithful and able officer, to whom is due the honour of conceiving and executing the great work of the Bell Rock Lighthouse …”

The words were of particularly significance as they were said in front of an audience that included Robert’s three sons, Alan, David and Thomas, who would continue this building dynasty for generations to come. The ‘Lighthouse Stevensons’ would go on to light up the coast of Scotland for many more years, saving countless lives as a result.

Published: January 29, 2017.