In 1843 the Church of Scotland was still a powerful and influential voice in the nation. Yet in that year it saw a third of its ministers and elders leave to form the Free Church of Scotland; what is called the Great Disruption. The new evangelical, fundamentalist Free Kirk was partly shaped by pioneers in photography, industry, engineering and science. Many of these figures remain well-known names, but their links to the Free Kirk are forgotten.

By the late 1700s, Church of Scotland ministers were roughly split between Moderates and Evangelicals. The latter tend to get a bad press, but it’s important to see beyond the stereotypes; they were more likely than Moderates to favour secular political reforms, such as the widening of the franchise. Their support for secular reform reflected the tension within the Kirk over Patronage.

Historically, Church of Scotland members chose their own ministers. Patronage was the practice whereby wealthy patrons exercised the right to appoint ministers to local churches, similar to livings being conferred in the Church of England. It was introduced to the Kirk by the 1711 Patronage (Scotland) Act. Evangelicals always vigorously opposed it.

During the 1830s the Kirk’s General Assembly tried to establish a right of veto over patronage decisions. This put it on a collision course with the Westminster Government. Kirk ministers met in Edinburgh and tried to convince the government that they weren’t troublemakers but rather were acting according to spiritual principle. However, at this meeting plans were first discussed for a breakaway church.

When the General Assembly opened in 1843, the retiring Moderator read out a prepared protest, bowed to the Queen’s Commissioner, and walked out. He was followed by 200 other ministers and elders who then formed a dramatic procession to the nearby Tanfield Hall, where they declared a new Free Church of Scotland. The popular academic and former minister of the Tron Kirk in Glasgow, Thomas Chalmers, was elected as its first Moderator.

In total, 474 ministers quit the Kirk as a result of the Disruption. Each of them willingly signed away their stipends, their manses and their churches, leaving them homeless and in some cases without an income.

The most striking record of the Disruption is a vast painting by David Octavius Hill that shows many of the seceding ministers and elders signing the document that split them from the Kirk. The painting is impressive in scale, perhaps, rather being a work of art. Hill was also a pioneering photographer. To help him with the painting, he took photographs of his subjects to help him remember their features. Many of these survive, in ghostly monochrome, among the earliest photographic portraits.

The painting portrays over 450 of those present in 1843, but it took Hill 23 years to complete. He needed those photographs: many attendees had died by the time the painting was completed. The painting is still owned by the Free Kirk and usually hangs in their Edinburgh offices, but is sometimes loaned to galleries for exhibition.

Hill and Adamson were not the only pioneers in science and technology associated with the Free Kirk. This aspect of the new church has been almost completely forgotten so it is worth looking at some of these figures in detail.

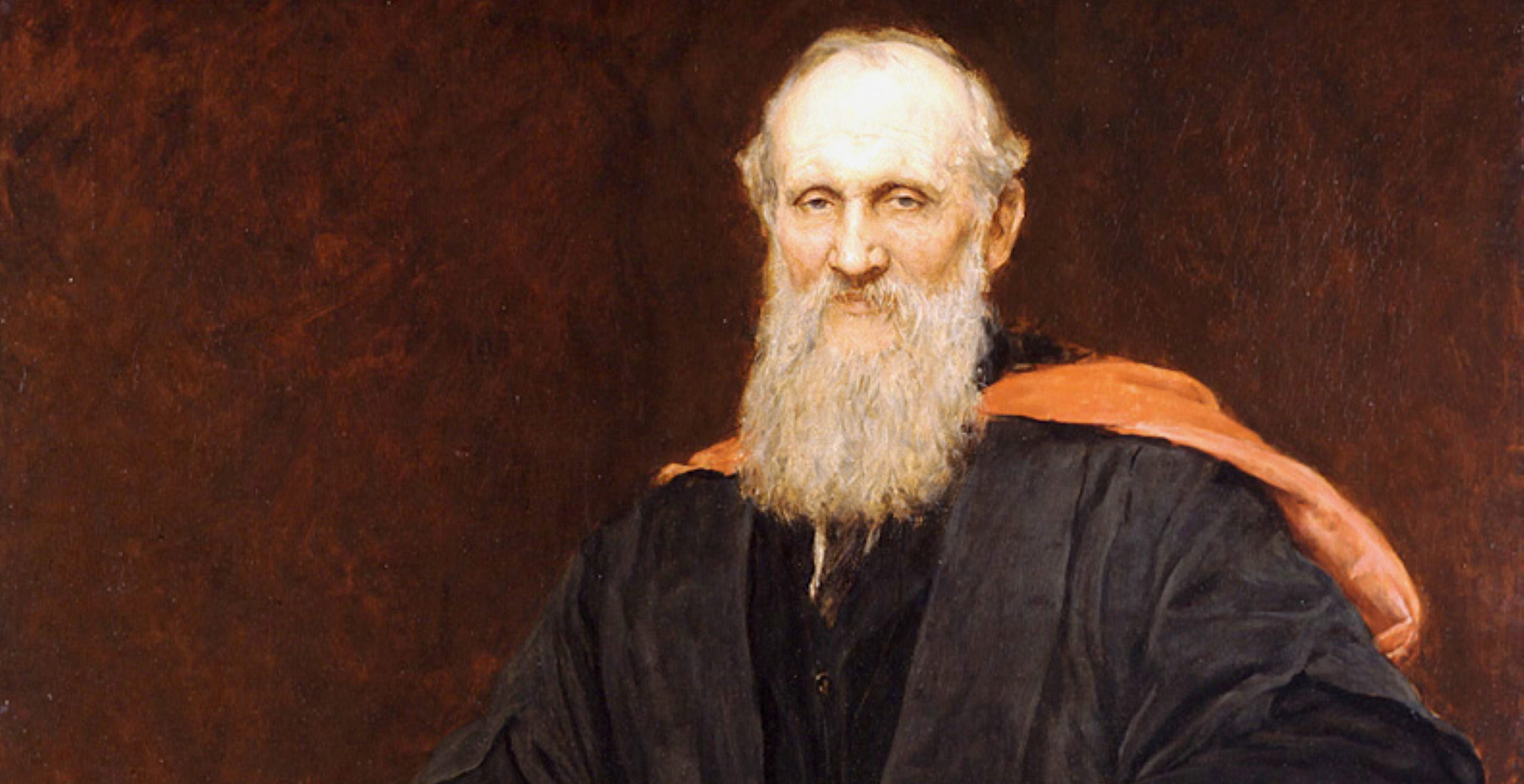

Sir David Brewster (1781-1868) was a scientist, polymath and, in 1816, inventor of the kaleidoscope (the HD-TV of its day). He had originally studied for the ministry but had grown interested in physics, particularly optics. Brewster was among the founders of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1831. He was appointed Principal of St Salvator’s and St Leonard’s at St Andrews University in 1838 and later became Principal of Edinburgh University. He had become interested in photography through his friendship with the pioneering William Fox Talbot. Brewster was one of the first people to write about photography in any depth; he was a valuable associate of Octavius Hill. Brewster features in the Disruption painting.

Sir James Young Simpson (1811-70) pioneered the use of chloroform as an anaesthetic, particularly in childbirth. He is regarded as one of the founders of gynaecology and was appointed Professor of Midwifery at Edinburgh University in 1840 and physician to Queen Victoria in Scotland in 1847. He also appears in the Disruption painting.

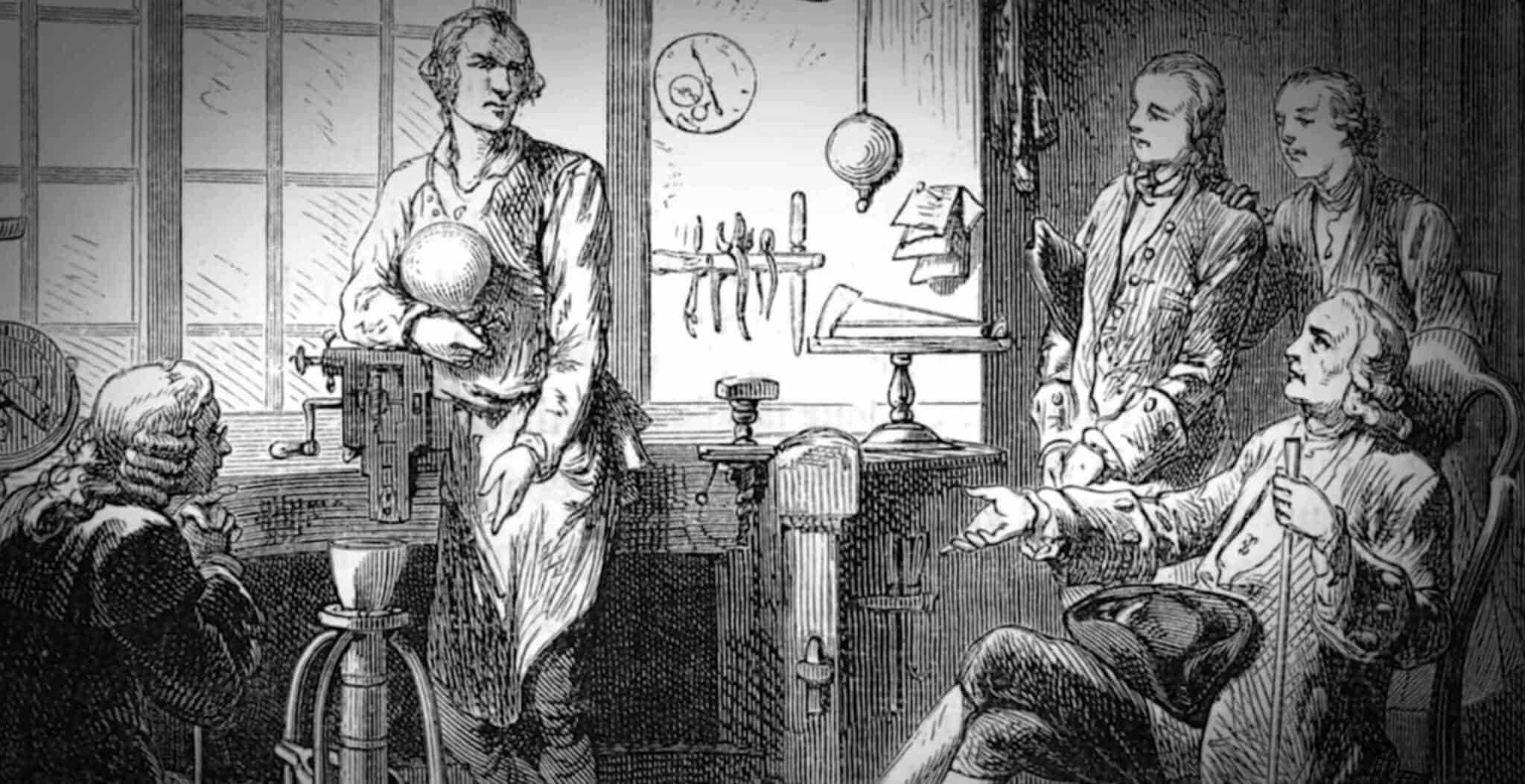

The effects of liquid chloroform on Sir J. Y. Simpson and his friends. The shattered drinking-glass used by one of the experimenters lies on the floor. Circa 1840s. Wellcome Library, London.

The effects of liquid chloroform on Sir J. Y. Simpson and his friends. The shattered drinking-glass used by one of the experimenters lies on the floor. Circa 1840s. Wellcome Library, London.

Hugh Miller (1802-1856) was from Cromarty and trained as a stonemason. He was fascinated by the fossils he encountered and became a self-taught pioneering geologist and palaeontologist. A talented writer, journalist and communicator, Miller sadly struggled with mental health issues and eventually took his own life. A picture of him portrayed as a noble stonemason, taken by his fellow Free Kirk secessionists Hill and Adamson, is one of the best-known early Scottish photographs. He is also easily recognisable in the Disruption painting.

James Beaumont Neilson (1792-1865) revolutionised the iron-smelting trade that was one of the drivers of the Industrial Revolution. Neilson studied how to improve the efficiency and economy of blast furnaces. He came up with the idea of using hot air, rather than cold, in the furnace. This greatly increased the efficiency of the blast. Honours were heaped on Neilson; he was even elected a member of the Royal Society in 1846. By then, of course, he was a member of the Free Kirk.

Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) was an ordained Kirk minister but also a professor of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews University and of Theology at Edinburgh. He is regarded as the leading figure in the Disruption and served as the Free Kirk Assembly’s first Moderator. Chalmers was a prolific writer, thinker and polymath who ought to be much better known. He served for several years as the Vice President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The technological, scientific and artistic background of some of the Free Kirk pioneers is at odds with the dismal stereotype of a backward sect. More than this, its heritage from the radical roots of the Evangelical movement in the Church of Scotland were quickly felt. When the Highlands, an area in which the Free Kirk was strong, was struck by potato famine in the late 1840s the church was quick to set up an efficient system of food distribution, which went not just to the Free Kirk hungry, but to all those afflicted, including Roman Catholics. TM Devine has written that ‘…the birth of the Free Church released an enormous evangelical religious energy that fed into the building of new churches, philanthropic endeavours and missionary work throughout the empire and beyond.’

The new church had an unfortunate clash with the abolitionist movement. The Free Kirk was short of buildings and money. Appeals for funding reached America, but an estimated £3000 of the cash raised was reported to have come from slaveholders. During 1846 many, including the former slave Frederick Douglass who was in Scotland at the time, urged the Free Kirk to ‘Send Back the Money’. The Free Kirk survived the controversy but it cast a shadow over its early years.

It seems unfortunate that, in the big picture of 19th century church history, the Disruption is drowned out by squabbles in England; the Oxford Movement, Dover Beach and Wilberforce v Huxley. The Disruption, and the church to which it gave birth, deserve to be viewed with fresh, unprejudiced eyes.

David McVey lectures in Humanities at New College Lanarkshire. He has published over 150 short stories and a great deal of non-fiction that focuses on history and the outdoors. He enjoys hillwalking, visiting historic sites, reading, watching telly, and supporting his home-town football team, Kirkintilloch Rob Roy FC.

Published: 12th March 2025.