The sound of the pipes on a Scottish battlefield echoes through the ages. The original purpose of the pipes in battle was to signal tactical movements to the troops, in the same way as a bugle was used in the cavalry to relay orders from officers to soldiers during battle.

After the Jacobite Rebellions, during the late 18th century a number of regiments were raised from the Highlands of Scotland and by the early 19th century these Scottish regiments had revived the tradition with pipers playing their comrades into battle, a practice which continued into World War I.

The bloodcurdling sound and swirl of the pipes boosted morale amongst the troops and intimidated the enemy. However, unarmed and drawing attention to themselves with their playing, pipers were always an easy target for the enemy, no more so than during World War One when they would lead the men ‘over the top’ of the trenches and into battle. The death rate amongst pipers was extremely high: it is estimated that around 1000 pipers died in World War One.

Piper Daniel Laidlaw of the 7th Kings Own Scottish Borderers was awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallantry in World War One. On September 25th 1915 the company were preparing to ‘go over the top’. Under heavy fire and suffering from a gas attack, the company’s morale was at rock bottom. The commanding officer ordered Laidlaw to start playing, to pull the shaken men together ready for the assault.

Immediately the piper mounted the parapet and began marching up and down the length of the trench. Oblivious to the danger, he played, “All the Blue Bonnets Over the Border.” The effect on the men was almost instant and they swarmed over the top into battle. Laidlaw continued piping until he got near the German lines when he was wounded. As well as being awarded the Victoria Cross, Laidlaw also received the French Criox de Guerre in recognition of his bravery.

During World War II, pipers were used by the 51st Highland Division at the start of the Second Battle of El Alamein on 23 October 1942. As they attacked, each company was led by a piper playing tunes that would identify their regiment in the darkness, usually their company march. Although the attack was successful, losses among the pipers were high and the use of bagpipes was banned from the frontline.

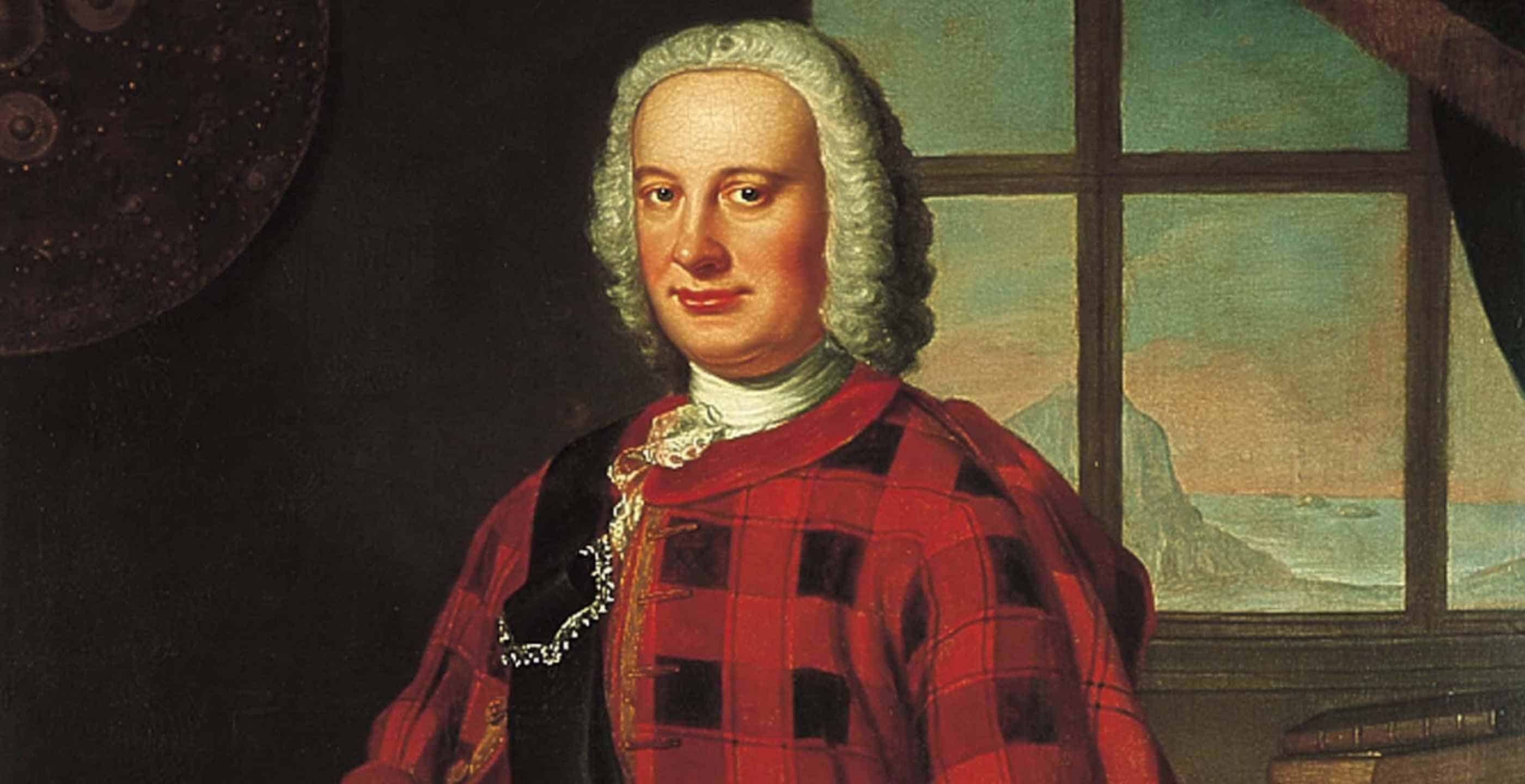

Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, was commander of 1st Special Service Brigade for the Normandy landings on D-Day 6th June 1944, and brought with him his 21-year-old personal piper, Bill Millin. As the troops landed on Sword Beach Lovat ignored the orders restricting the playing of bagpipes in action, and ordered Millin to play. When Private Millin quoted the regulations, Lord Lovat is said to have replied: “Ah, but that’s the English War Office. You and I are both Scottish, and that doesn’t apply.”

Millin was the only man during the landings who wore a kilt and he was armed only with his pipes and the traditional sgian-dubh, or “black knife”. He played the tunes “Hielan’ Laddie” and “The Road to the Isles” as men all around him fell under fire. According to Millin, he later talked to captured German snipers who claimed they did not shoot him because they thought he was mad!

Lovat, Millin and the commandos then advanced from Sword Beach to Pegasus Bridge, which was being heroically defended by the men of the 2nd Battalion The Ox & Bucks Light Infantry (6th Airborne Division) who had landed in the very early hours of D-Day by glider. Arriving at Pegasus Bridge, Lovat and his men marched across to the sound of Millin’s bagpipes under heavy fire. Twelve men died, shot through their berets. To better understand the sheer bravery of this action, later detachments of the commandos were instructed to rush across the bridge in small groups, protected by their helmets.

Millin’s actions on D-Day were immortalised in the 1962 film, ‘The Longest Day’ where he was played by Pipe Major Leslie de Laspee, later the Queen Mother’s official piper. Millin saw further action in the Netherlands and Germany before being demobbed in 1946. He died in 2010.

Millin was awarded the Croix d’Honneur by France in June 2009. In recognition of his gallantry and as a tribute to all who contributed to the liberation of Europe, a bronze life-size statue of him will be unveiled on 8th June 2013 at Colleville-Montgomery, near Sword Beach, in France.