For centuries, pirates have been shrouded in mystery and intrigue, famous in literature and popular culture as fearsome characters, such as Henry Morgan, “Calico” Jack Rackham and Blackbeard.

Whilst pirates have existed since the ancient empires of Rome and Greece, it was not until the sixteenth century that piracy reached its height, when European imperial domination resulted in ships taking to the seas to find wealth and prestige in distant lands.

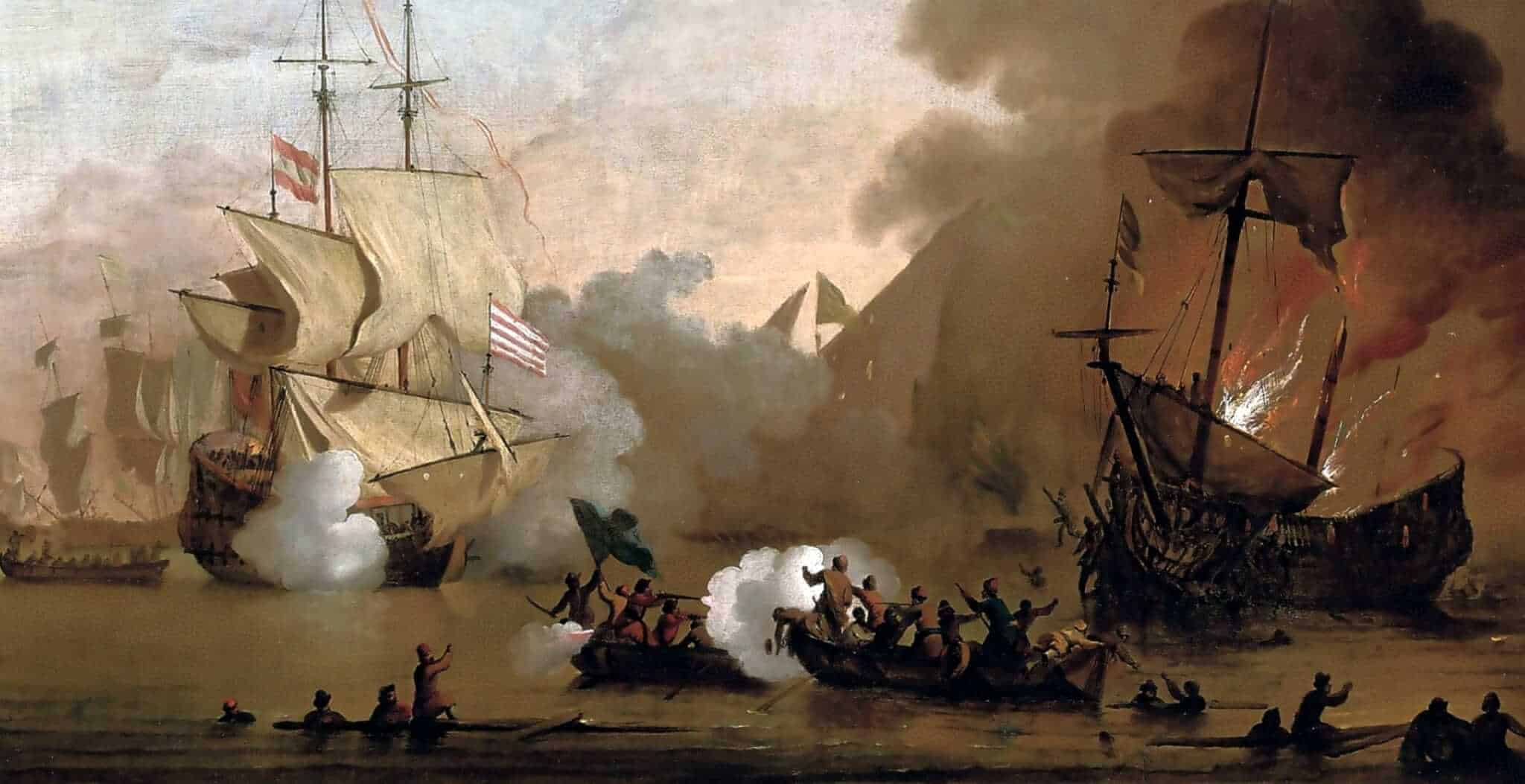

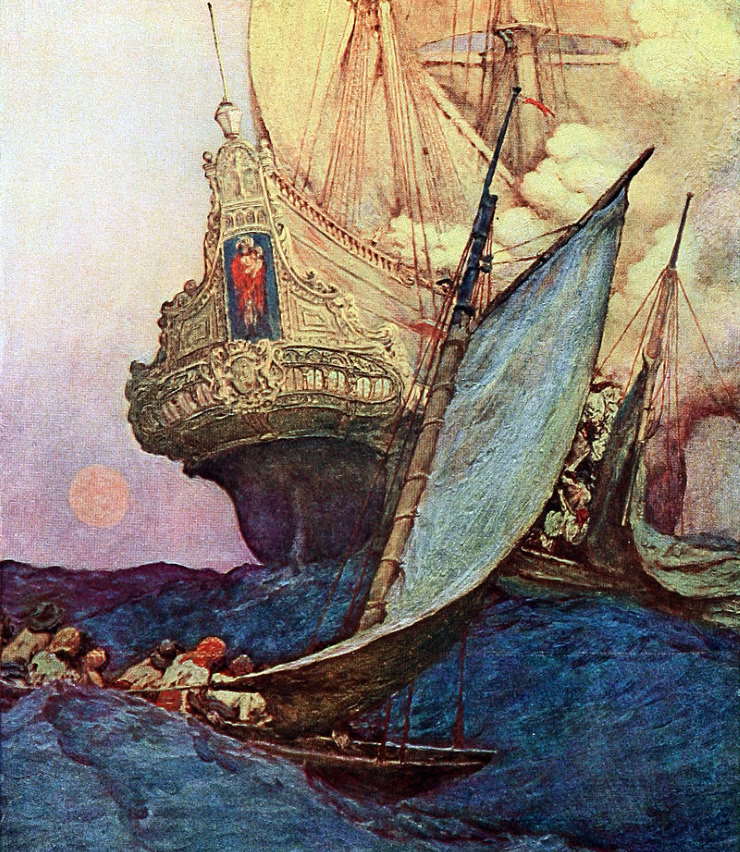

The Spanish became famous for using large imposing ships known as galleons, which returned to Europe with vast amounts of goods that, for pirates, proved too irresistible not to plunder. During this time pirate attacks on these ships reached such a peak that the galleons were forced to sail in fleets, protected by armed vessels. There was much money to be made from stealing their precious cargo and for the pirates, the possible rewards made it definitely worth the risk.

In time, the Spanish began to build settlements in these faraway territories, both on the American mainland and on the Caribbean islands. Coastal towns, ports and ships were open to constant attack from pirates. By the seventeenth century piracy had reached its pinnacle, so much so that this period became known as the “Golden Age of Piracy”.

Back across the Atlantic, one particular pirate decided to concentrate his activities much closer to home. There was no need to travel as far as the Caribbean, especially with all the risks that entailed, instead a man called John Callis (also known as John Callice) became a pirate in Britain where the Welsh coastline became his domain.

Born in the 1500’s in Monmouthshire, Callis moved to London when he was young and became a retailer. Soon afterwards, his professional ambitions changed and he joined the Navy. It was in this role that he would first start seizing and selling cargo. As he became more confident in his abilities, his piratical activities escalated.

This sixteenth century Welsh pirate was particularly active in the region of South Wales, between Cardiff and Haverfordwest. He would spend his time selling his stolen cargo in the villages along the way such as Laugharne and Carew.

Cardiff provided a useful base, not only for Callis but for many others like him. It became a notorious port used by pirates who took advantage of the complicit authorities and aristocratic public figures who often turned a blind eye to their illegal activities. Callis in particular benefited from important connections as Nicholas Herbert, his father-in-law, came from an important family with much wealth.

Moreover, pirates and those buying stolen products could conceal much of what they were doing from the authorities in England by using the Welsh language to remain undiscovered. Cardiff became the playground for pirates in this period.

John Callis became one of the most infamous pirates of his time, well-known by all and wanted by many. For several years he successfully terrorised the ships along the Severn estuary as well as the Bristol Channel.

Local officials, such as the Cardiff Magistrate Thomas Lewes, often released arrested pirates on bail, only for them to resume their illegal activities. It was this culture of turning a blind eye to piracy that allowed them to flourish and thus created the “golden age” for Callis and his fellow pirates.

Thomas Lewes was certainly not the only figure to treat the pirates so leniently. The Vice Admiral for South Wales at the time, SWir John Perrott had also been found to be in cahoots with them and was reprimanded for not tackling Callis with enough rigour. He even received a reproach from the Privy Council for letting such a notorious and repeat offender such as Callis escape.

That being said, locals in his pay were not the only guilty parties. The Privy Council itself did not largely object to the criminality of piratical activities against the Spanish, who were after all, Britain’s imperial rivals.

In the case of John Callis, his growing reputation and notoriety did not sit well with those in government. His targets proved to be indiscriminate: he had no qualms about attacking any ship that took his fancy. The result was that the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, French, Danish and Scottish all became his victims. Callis’s plunder included such goods as olives, almonds, valuable Scottish salmon and, of course, money.

The trickery used by pirates like Callis often involved displaying a white mast which lulled other ships into a false sense of security. Of course, these tactics led to numerous complaints from the likes of foreign ambassadors who petitioned the Privy Council on a regular basis. Francis Walsingham of the Privy Council was in receipt of numerous complaints, frequently from Spanish and French ambassadors who despaired at the lack of progress in catching and reprimanding scoundrels such as Callis.

Unfortunately for those complainants, England’s legal system was not particularly receptive to claims from foreigners. Nevertheless, piracy did carry a punishment and hangings at Wapping and other locations were commonplace.

Whilst piracy was never viewed as either a legal or acceptable business practice, a great deal of complicity would result in the burgeoning successes of Callis and likeminded individuals. Callis however, quickly drew attention to his activities because of his barbarous tactics. For example, the French were enraged at his acts of torture against their mariners, a brutality which was duly noted by Walsingham.

Unfortunately, this level of cruelty did not prove to be a one off. The threat of torture, mistreatment and maiming put a target on Callis’s head: the authorities were after him.

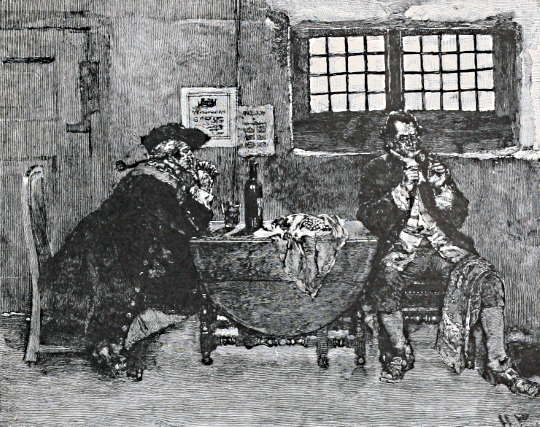

Now a relatively old man, Callis spent his time hiding in different inns and houses in an attempt to evade the authorities. One of the locations he stayed in was the Point House Inn in Pembrokeshire. Unfortunately for Callis, his luck eventually ran out and in 1576 he was finally captured and thrown into Marshalsea Prison in London.

In order to save himself, he offered up information about other pirates, their activities, whereabouts and other pertinent information. One of the most valuable secrets he chose to share in order to have his life spared was the involvement of important Welsh figures in his piracy, including the mayor of Cardiff and the Sheriff of Glamorgan.

His death remains a bit of a mystery. Some believe that after bartering for his life he was later tried and hanged in Newport, whilst others claim that due to his powerful connections he was released and later commissioned to join Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s voyage to the Americas alongside Walter Raleigh.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.