In the mid 1700’s, Merthyr Tydfil was just a small Welsh farming village in the upper Taff Valley.

Like the Seven Valley a little further to the north and east, at Ironbridge in Shropshire, the upper Taff valley contained all of the necessary ingredients for a successful iron industry – iron ore, limestone for lining furnaces, mountain streams to provide water power and forests to supply timber for the manufacture of charcoal.

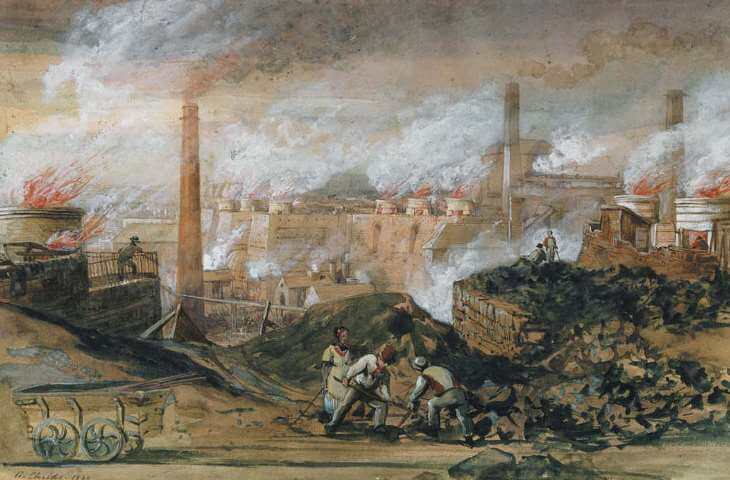

With these necessary ingredients in place, ironworks were established at Dowlais in 1759 and at Cyfarthfa by John Guest under the control of the Crawshay family. It was John Guest however who discovered coal in the valley and used this to replace charcoal for smelting, increasing production rates.

Thomas Guest succeeded his father in 1787 and he introduced steam power to Dowlais for blowing the furnaces with a Watt steam engine in 1795, increasing production rates still further.

Unlike the their competitors in Ironbridge however, Merthyr Tydfil and the other iron producers of the south Wales coalfield were poorly placed with regard to the transport of their products to the ports. As crazy as it now sounds, pig iron was initially carried to the coast by packhorses.

Roads were eventually built but, whilst a wagon drawn by four horses could haul two tons of iron, a canal barge drawn by one horse could tow a massive twenty-five tons of freight and cargo.

And so by 1800 all the main valleys of South Wales had been linked to ports by canals, and it was the canals which truly launched the iron and coal industries of south Wales on their spectacular growth.

But it was to be when Josiah Guest, the only surviving son of Thomas Guest, took control over his father’s ironworks in 1807 that even bigger changes were to be seen.

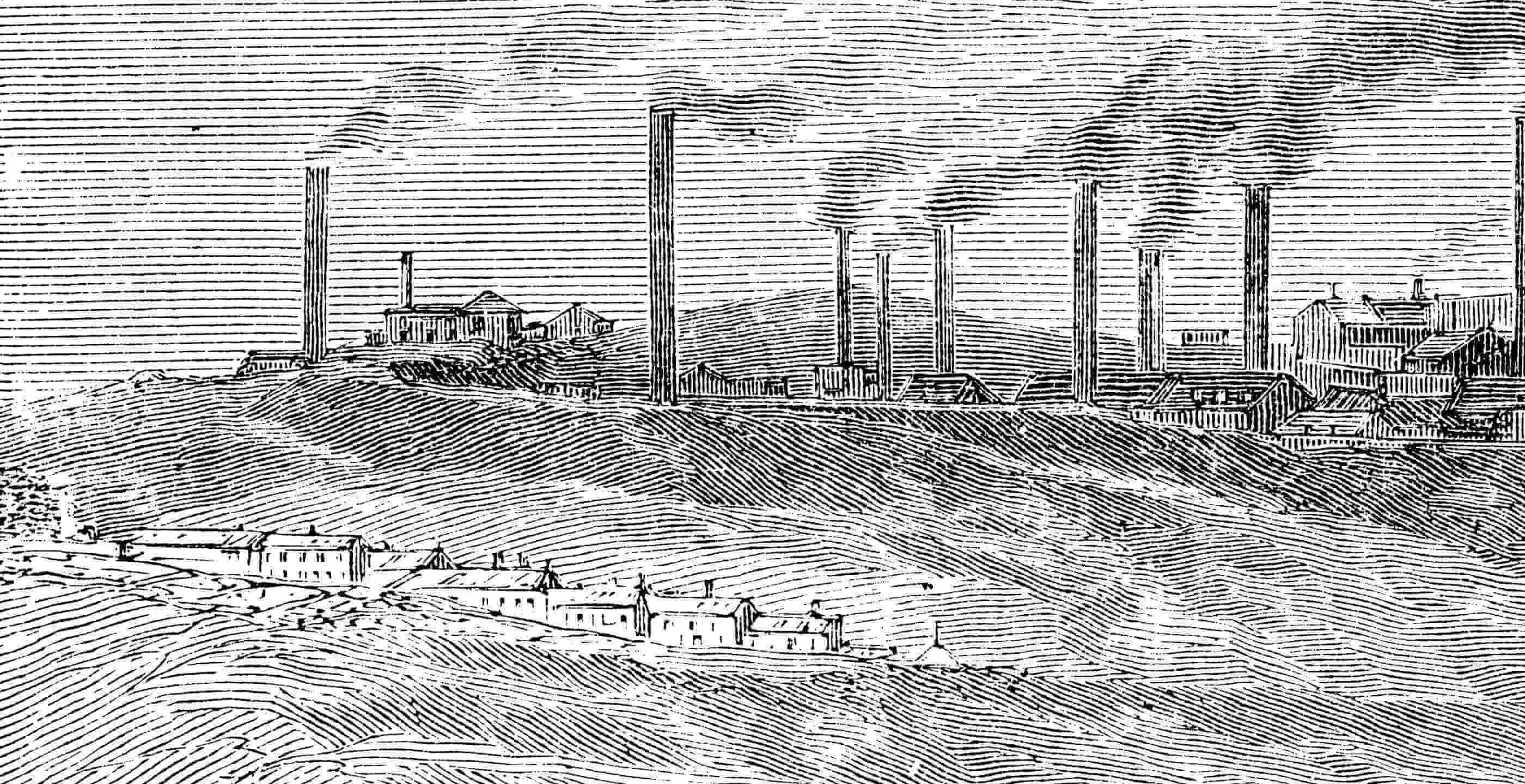

Josiah was a shrewd businessman and by the 1830s the Dowlais Ironworks was the largest in the world, employing more than 5,000 people.

And with the increased size of the ironworks, so the size of Merthyr soared. In 1801 a population of 7,700 was recorded, which rose to 22,000 in 1831 and to 46,000 in 1851, establishing Merthyr as by far the largest town in Wales.

The ironmasters of Merthyr were innovators as well as good businessmen, adopting new manufacturing processes (Cort & Bessemer) which significantly increased the rate at which iron and steel could be produced. The process became so widely adopted that it become known as the Welsh method.

By the 1820s, Merthyr was the source of 40% of Britain’s iron exports. It was an area which produced iron rather than things made of iron: the skills required to work the metal ensured the prosperity of cities such Sheffield and Birmingham.

When the railway age arrived, Guest immediately recognised the advantages in directly linking his ironworks with Cardiff docks. And so, in conjunction with Anthony Hill the owner of another nearby ironworks, they formed the Taff Vale Railway Company and employed a talented young engineer from just along the road at Bristol, one Isambard Kingdom Brunel, to build the railway for them.

Brunel completed the Taff Vale Railway in 1841, and this allowed Guest and Hill to transport their iron and steel from Merthyr to Cardiff in less than an hour. Later, branch lines were built which linked the mining valleys with the Welsh ports and into England’s fast growing towns and cities, providing the raw materials which continued to power the industrial revolution.

The railway network influenced transport costs so much that it even proved profitable to export Welsh coal to countries as far flung as Argentina and India.

Merthyr maintained its supremacy as the world’s number 1 ‘Iron and Steel Town’ until the 1850’s when new manufacturing processes demanding purer iron ore saw it lose this mantle.