After defeating the Germans in Normandy in 1944, and ‘swanning’ through Belgium, the Allied armies were fighting to liberate Holland in the winter months of 1944. Beginning on 22nd October 1944, operation ‘PHEASANT’ was designed to clear the Scheldt in the Netherlands and allow the port of Antwerp to be used by the Allies for supply. ‘PHEASANT’ was broken down into smaller sub-operations, codenamed ‘COLIN’ and ‘ALAN’.

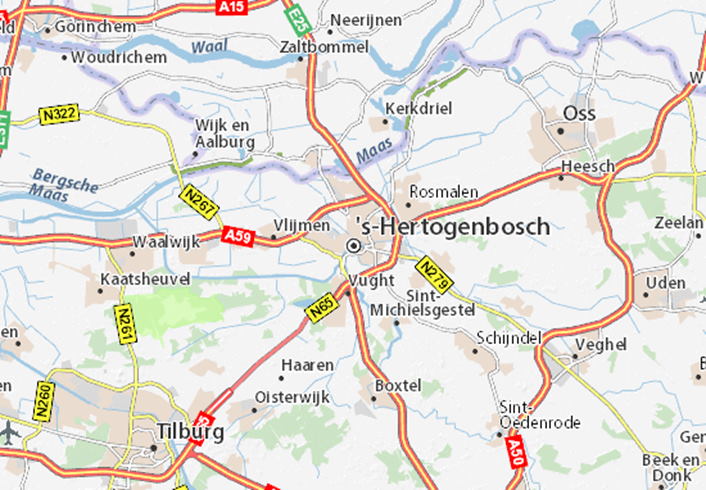

Operation ‘ALAN’ tasked the 53rd ‘Welsh’ and the 7th Armoured Divisions with clearing the city of S’Hertogenbosch – henceforth referred to as ‘Den Bosch’ – a medieval fortress city of roughly 50,000 inhabitants intersected by canals, rivers and waterways. Knowing that the Germans realised its importance, Allied intelligence made great efforts to reveal which German units were garrisoning the city. They established that Den Bosch was defended by four battalions of the 712th Infanterie Division, along with three battalions from the Fallschirmjäger training regiment based there. Further reinforcements from Feld-Ersatz Battalion 347 were also absorbed into the city’s defences.

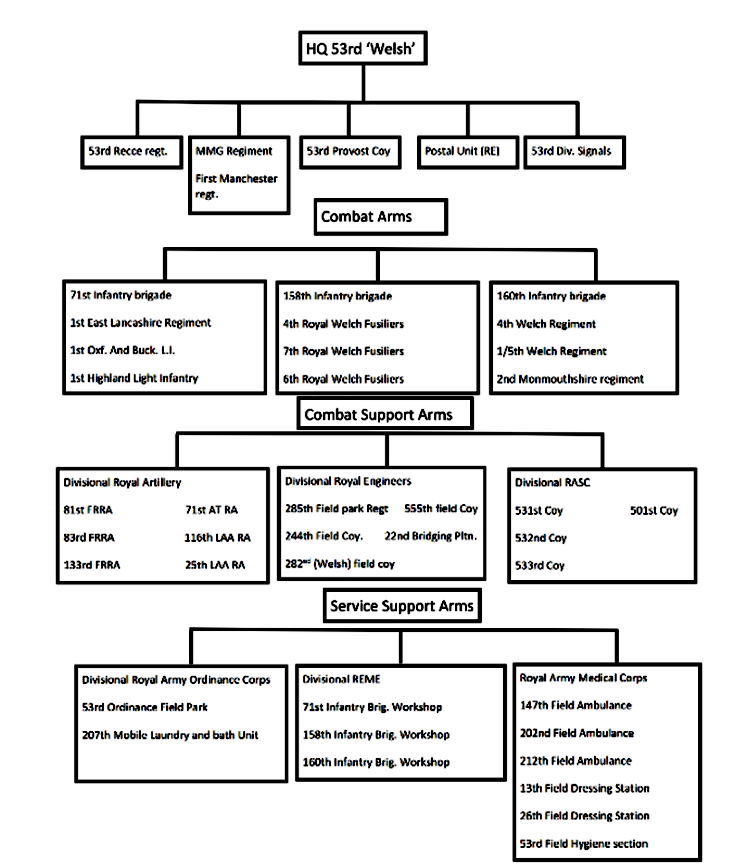

The commander of the 53rd, Major General ‘Bobby’ Ross, planned that the attack was to come in from east to west, from the direction of Oss. 160 Brigade supported by the tanks of the 5th Dragoon Guards and some flame throwing Churchill Crocodile tanks would move north along the railway that spans from Oss to Den Bosch. 71 Brigade would advance from the south of the railway astride the Heesch – Den Bosch road. 158 Brigade, in reserve, was to pass through with the 53rd Reconnaissance Regiment and one squadron of the 5th Dragoon Guards and would seize the canal bridges in the town should an opportunity occur.

At 0630hrs on 22nd October, 200 artillery pieces fired on all known German positions. A few minutes later, Brigadier Coleman’s 160 Brigade advanced with the 2nd Battalion the Monmouthshire Regiment on the north side of the railway, and the 4th Battalion the Welch Regiment with Crocodile tanks to the south. 4th Battalion the Welch Regiment under Lt. Col Spurling advanced into Nuland, a village defended by a battalion of fusiliers from the 712 Infanterie Division. Major Lewis, Officer Commanding of ‘A’ Company wrote:

‘The attack was now in full swing, despite shells bursting everywhere, we pressed on at top speed, trying to keep under our barrage, never allowing ourselves to be pinned down. Lt Andrew Wilson’s 141 RAC ‘Crocs’ sped past us belching flame and we went in on top of the flame fixed with bayonets, into the trenches went the men, grenades first, then bayonets’.

Scenes of combined arms and close-combat warfare like this typify the attacks on Den Bosch, and it can be said that this experience for 4 Welch was common for the men of the entire 53rd Division. The 2nd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment had killed an estimated 48 Germans and captured 177, with the cost of only 7 men who were wounded. By 0745hrs, Nuland was clear. Two German battalions retreated to Den Bosch, while the 53rd’s engineers cleared the roads of mines and obstacles. The division was now 5 miles from the city centre.

On 23rd October, 71 Brigade were to slowly keep advancing while the other two brigades were to manoeuvre to the outskirts of the city, where more attempts would be made to break in. At 0715, 2 Mons passed through the positions of 71 Brigade, supported by four Crocodiles and B Squadron of the 5th Royal Dragoon Guards. Their objective was the village of Bruggen, a hamlet on the road to Rosmalen. The war diary of 2 Mons records that ‘the attacks were successful in clearing the village by 0815’, with the capture of 42 prisoners and 24 enemy killed. Major R.N Deane, commander of ‘A’ Company remembered:

‘It worked a charm. The boys went in like daemons and went straight through, shooting any bosch who hadn’t dived for cover from the flame, which was terrific. It was great fun. The boys were really wild, and I saw the most harmless lads bayoneting bosch and shooting them as they ran away. The really close infantry and tank co-operation and the whole party became a mass of fighting’.

It was clear in the diary extract that the men of the 53rd had certainly become accustomed to the horrors of war, desensitised to killing. When compared to earlier diary extracts from Normandy, it is clear that this inexperienced division had come a long way. C’ Company, 2 Mons worked with 4 Welch clearing the woods south of Bruggen, while ‘D’ Company passed through Bruggen and cleared Rosmalen, which the Germans had abandoned contrary to their orders. As planned, 71 Brigade did not push too strongly and kept the Germans pinned down and busy south east of 160 Brigade’s operations around Rosmalen.

On 25th October, the sappers of the 224th Field Company were exhausted and in dire need of rest after days of bridge laying and repairing. Unfortunately, heavy German shellfire kept the weary engineers awake all evening. In such a rush, Lieutenant Dick Brown dove into a slit trench and ended up lying on top of many officers, including his Officer Commanding! The officers groaned at Brown for making them so uncomfortable, however his reply brought fits of laughter; ‘Talk of discomfort! It’s alright for you, you’ve got six inches of human headcover to keep the bits out. What about me?!’. Graciously, the only casualties were tents and drying laundry. Although the men were exhausted and under fire, they managed to maintain their dry British sense of humour – an important component of morale.

Major-General Ross began to devise the final plan for the assault on the city – an ambitious night attack. Arial photographs were issued to commanders, along with an artillery fire plan that would bring 200 guns to bear on the city, helping the division advance. 158 Brigade’s advance went well, with 6th Royal Welch Fusiliers taking and defending the hamlet of Varkenshoek east of the city.

When the infantry reached Den Bosch, the fighting became a series of confusing and claustrophobic street-fighting actions, centring on the bridges around the canal, most of which were damaged and had to be repaired or replaced by exhausted Royal Engineers. By the evening of the 26th, most of the city was in the hands of the 53rd, but it was not until the 27th that the city was completely clear.

The liberation of Den Bosch did not come without a price for a grateful Dutch population. Unfortunately, the 90,000 shells thrown into the city caused around 250 civilian casualties and reportedly 700 buildings were completely destroyed. No building was untouched by the artillery. The battle of Den Bosch was largely a Welsh one. Although there were English, Scots and Irishmen within the ranks of the 53rd Division, it is to Wales that the modern population are thankful.

The city incorporated many Welsh names and landmarks when rebuilding their city during the period of post-war reconstruction, the most obvious example being the ‘Royal Welsh’ Bridge. The names of the 146 men who were killed liberating the city were engraved on to it in 2015. Moreover, the city hall flies a Welsh flag and a large public space containing a war memorial was renamed ‘53rd Welsh Division Square’ following the liberation. Den Bosch remains an important reminder of the sacrifices made by the British and Dominion forces to rid Europe of Nazi occupation.

By Lewys Phillips. Lewys is currently undertaking a Modern History Master’s degree at Swansea University. Currently serving in the 3rd Battalion the Royal Welsh and set to graduate in December 2020, he hopes to go on to gain a PhD after a military career. Focusing on the British Army in the Second World War, Lewys wrote a 10,000 word dissertation on the experiences of the 53rd ‘Welsh’ Division and is currently writing a 20,000 word dissertation on the effectiveness of the 21st Army Group. His other interests include Nazi Germany, the American Civil War and the Napoleonic Wars.