Each year in late July and early August, flights arrive at London airports carrying folk from South America. Many of these visitors experience difficulty in understanding the English spoken to them at passport control, however once they have travelled along the M4 motorway and crossed the border into Wales, destined for wherever the National Eisteddfod is being held that particular year, they find that they can communicate fluently with the locals.

The visitors in question have travelled 8,000 miles from the Welsh speaking outpost of Patagonia, on the southern tip of Argentina. The fascinating history of how these visitors from an essentially Spanish speaking country, also come to speak the ‘language of heaven’ dates back to the first half of the 19th century.

In the early 1800’s, industry within the Welsh heart lands developed and rural communities began to disappear. This industry was helping to fuel the growth of the Industrial Revolution, with the supply of coal, slate, iron and steel. Many believed that Wales was now gradually being absorbed into England, and perhaps disillusioned with this prospect, or excited by the thought of a new start in a new world, many Welshmen and women decided to seek their fortune in other countries.

In the early 1800’s, industry within the Welsh heart lands developed and rural communities began to disappear. This industry was helping to fuel the growth of the Industrial Revolution, with the supply of coal, slate, iron and steel. Many believed that Wales was now gradually being absorbed into England, and perhaps disillusioned with this prospect, or excited by the thought of a new start in a new world, many Welshmen and women decided to seek their fortune in other countries.

Welsh immigrants had attempted to set up Welsh speaking colonies in order to retain their cultural identity in America. The most successful of these included ‘Welsh’ towns such as Utica in New York State and Scranton in Pennsylvania.

However these Welsh immigrants were always under great pressure to learn the English language and adopt the ways of the emerging American industrial culture. As such, it did not take too long for these new immigrants to be fully assimilated into the American way of life.

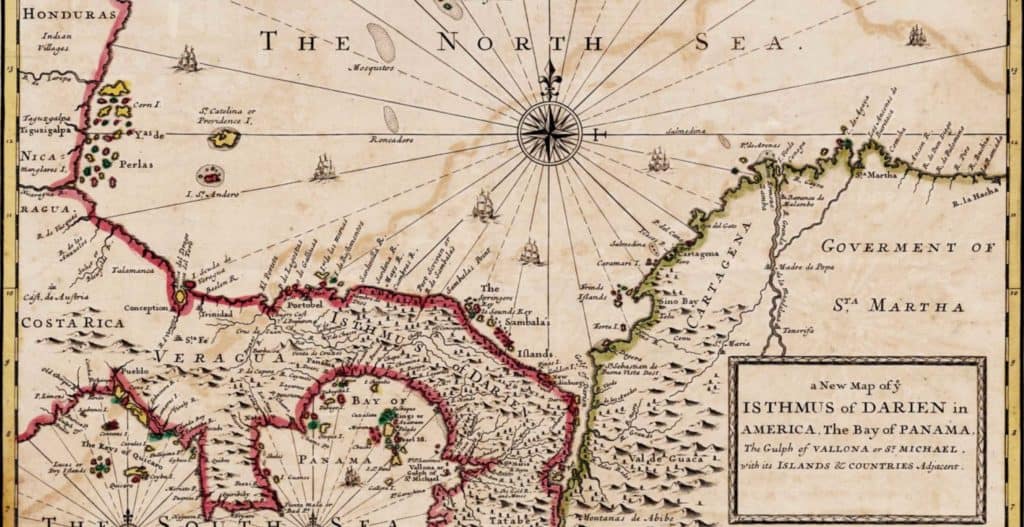

In 1861 at a meeting held at the Bala home of Michael D Jones in north Wales, a group of men discussed the possibility of founding a new Welsh promised land other than in the USA. One option considered for this new colony was Vancouver Island, in Canada, but an alternative destination was also discussed which seemed to have everything the colonists might need in Patagonia, Argentina.

Michael Jones, the principal of Bala College and a staunch nationalist, had been corresponding with the Argentinean government about settling an area known as Bahia Blanca, where Welsh immigrants would be allowed to retain and preserve their language, culture and traditions. Granting such a request suited the Argentinean government, as this would put them in control of a large tract of land which was then the subject of dispute with their Chilean neighbours.

A Welsh emigration committee met in Liverpool and published a handbook, Llawlyfr y Wladfa (Colony Handbook) to publicise the Patagonian scheme. The handbook was widely distributed throughout Wales and also in America.

The first group of settlers, over 150 people gathered from all over Wales, but mainly north and mid-Wales, sailed from Liverpool in late May 1865 aboard the tea-clipper Mimosa. Passengers had paid £12 per adult, or £6 per child for the journey. Blessed with good weather the journey took approximately eight weeks, and the Mimosa eventually arrived at what is now called Puerto Madryn on 27th July.

Unfortunately the settlers found that Patagonia was not the friendly and inviting land they had been expecting. They had been told that it was much like the green and fertile lowlands of Wales. In reality it was a barren and inhospitable windswept pampas, with no water, very little food and no forests to provide building materials for shelter. Some of the settlers’ first homes were dug out from the soft rock of the cliffs in the bay.

Despite receiving help from the native Teheulche Indians who tried to teach the settlers how to survive on the scant resources of the prairie, the colony looked as if it were doomed to failure from the lack of food. However, after receiving several mercy missions of supplies, the settlers persevered and finally struggled on to reach the proposed site for the colony in the Chubut valley about 40 miles away. It was here, where a river the settlers named Camwy cuts a narrow channel through the desert from the nearby Andes, that the first permanent settlement of Rawson was established at the end of 1865.

Despite receiving help from the native Teheulche Indians who tried to teach the settlers how to survive on the scant resources of the prairie, the colony looked as if it were doomed to failure from the lack of food. However, after receiving several mercy missions of supplies, the settlers persevered and finally struggled on to reach the proposed site for the colony in the Chubut valley about 40 miles away. It was here, where a river the settlers named Camwy cuts a narrow channel through the desert from the nearby Andes, that the first permanent settlement of Rawson was established at the end of 1865.

The colony suffered badly in the early years with floods, poor harvests and disagreements over the ownership of land, in addition the lack of a direct route to the ocean made it difficult to bring in new supplies.

History records that it was one Rachel Jenkins who first had the idea that changed the history of the colony and secured its future. Rachel had noticed that on occasion the River Camwy burst its banks; she also considered how such flooding brought life to the arid land that bordered it. It was simple irrigation and backbreaking water management that saved the Chubut valley and its tiny band of Welsh settlers.

Over the next several years new settlers arrived from both Wales and Pennsylvania, and by the end of 1874 the settlement had a population totalling over 270. With the arrival of these keen and fresh hands, new irrigation channels were dug along the length of the Chubut valley, and a patchwork of farms began to emerge along a thin strip on either side of the River Camwy.

In 1875 the Argentine government granted the Welsh settlers official title to the land, and this encouraged many more people to join the colony, with more than 500 people arriving from Wales, including many from the south Wales coalfields which were undergoing a severe depression at that time. This fresh influx of immigrants meant that plans for a major new irrigation system in the Lower Chubut valley could finally begin.

There were further substantial migrations from Wales during the periods 1880-87, and also 1904-12, again mainly due to depression within the coalfields. The settlers had seemingly achieved their utopia with Welsh speaking schools and chapels; even the language of local government was Welsh.

In the few decades since the settlers had arrived, they had transformed the inhospitable scrub-filled semi-dessert into one of the most fertile and productive agricultural areas in the whole of Argentina, and had even expanded their territory into the foothills of the Andes with a settlement known as Cwm Hyfryd.

But it was these productive and fertile lands that now attracted other nationalities to settle in Chubut and the colony’s Welsh identity began to be eroded. By 1915 the population of Chubut had grown to around 20,000, with approximately half of these being foreign immigrants.

The turn of the century also marked a change in attitude by the Argentine government who stepped in to impose direct rule on the colony. This brought the speaking of Welsh at local government level and in the schools to an abrupt end. The Welsh utopian dream of Michael D Jones appeared to be disintegrating.

Welsh however remained the language of the home and of the chapel, and despite the Spanish-only education system, the proud community survives to this day serving bara brith from Welsh tea houses, and celebrating their heritage at one of the many eisteddfodau.

Even more recently however, since 1997 in fact, the British Council instigated the Welsh Language Project (WLP) to promote and develop the Welsh language in the Chubut region of Patagonia. Within the terms of this project as well as a permanent Teaching Co-ordinator based in the region, every year Language Development Officers from Wales are dispatched to ensure that the purity of the ‘language of heaven’ is delivered by both formal teaching and via more ‘fun’ social activities.

Published: 1 July 2021