Some have said: ‘The Darien Venture was the most ambitious colonial scheme attempted in the 17th century… The Scots were the first to realise the strategic importance of the area… ” Whilst others claimed: “They were plain daft to try… It was disaster. They never had a chance.” T’is for you to decide!

William Paterson, a Scot whose other major claim to fame was the foundation of the Bank of England, was born in Tinwald in Dumfriesshire in 1658. He made his first fortune through international trade, travelling extensively throughout the Americas and West Indies.

Upon his return to his native Scotland, Paterson sought to make his second fortune with a scheme of epic proportion. His plan was to create a link between east and west, which could command the trade of the two great oceans of the world, the Pacific and Atlantic. In 1693, Paterson helped to set up the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies in Edinburgh to establish an entrepôt on the Isthmus of Darien (the narrow neck of land separating North and South America now known as Panama). It was claimed that the company would prosper through foreign trade and promoted Darien as a remote spot where Scots could settle.

The original directors of the Company of Scotland were Scottish and English in equal numbers, with the risk investment capital being shared half from the English and Dutch, and the other half from the Scots. However, under pressure from the East India Company, afraid of losing their trade monopoly, the English Parliament withdrew its support for the scheme at the last minute, forcing the English and Dutch to withdraw and leaving the Scots as sole investors.

There were no shortage of takers though, as thousands of ordinary Scottish folk invested money in the expedition, to the tune of approximately £500,000 – about half of the national capital available. Almost every Scot who had £5 to spare invested in the Darien Scheme. Thousands more volunteered to travel on board the five ships that had been chartered to carry the pioneers to their new home where Scots could settle, including famine driven Highlanders and soldiers discharged following the Glen Coe Massacre.

But, who had actually been out to see this Promised Land, this remote spot where Scots could settle? Well not Paterson apparently! The pioneers had wrongly believed, on the basis of sightings by sailors and pirates, that Darien offered them a colony where entrepreneurs could establish trading links with the world and bring prestige and prosperity to their country. And so it was with much fanfare and excitement that the ships sailed from Leith harbour on 12 July 1698 with 1,200 people on board.

It was however, a depleted and less excited group of pioneers that arrived on the mosquito-infested scrap of land known as Darien on 30 October 1698. Many were already sick and others were quarrelling as power struggles arose among the elected councillors. They struggled ashore and renamed the land Caledonia, with its capital New Edinburgh. The first task was to dig graves for the dead pioneers, which included Paterson’s wife. The situation grew worse because of a lack of food and attacks from hostile Spaniards. The native Indians took pity on the Scots, bringing them gifts of fruit and fish. Seven months after arriving, 400 Scots were dead. The rest were emaciated and yellow with fever. They decided to abandon the scheme.

Sadly, news did not travel quickly in the 17th century. Six more ships set sail from Leith in November 1699 loaded with a further 1,300 excited pioneers, all blissfully ignorant about the fate of the earlier settlers. Whoever said that bad news travels fast was obviously not a Scot as a third fleet of five ships left Leith shortly after.

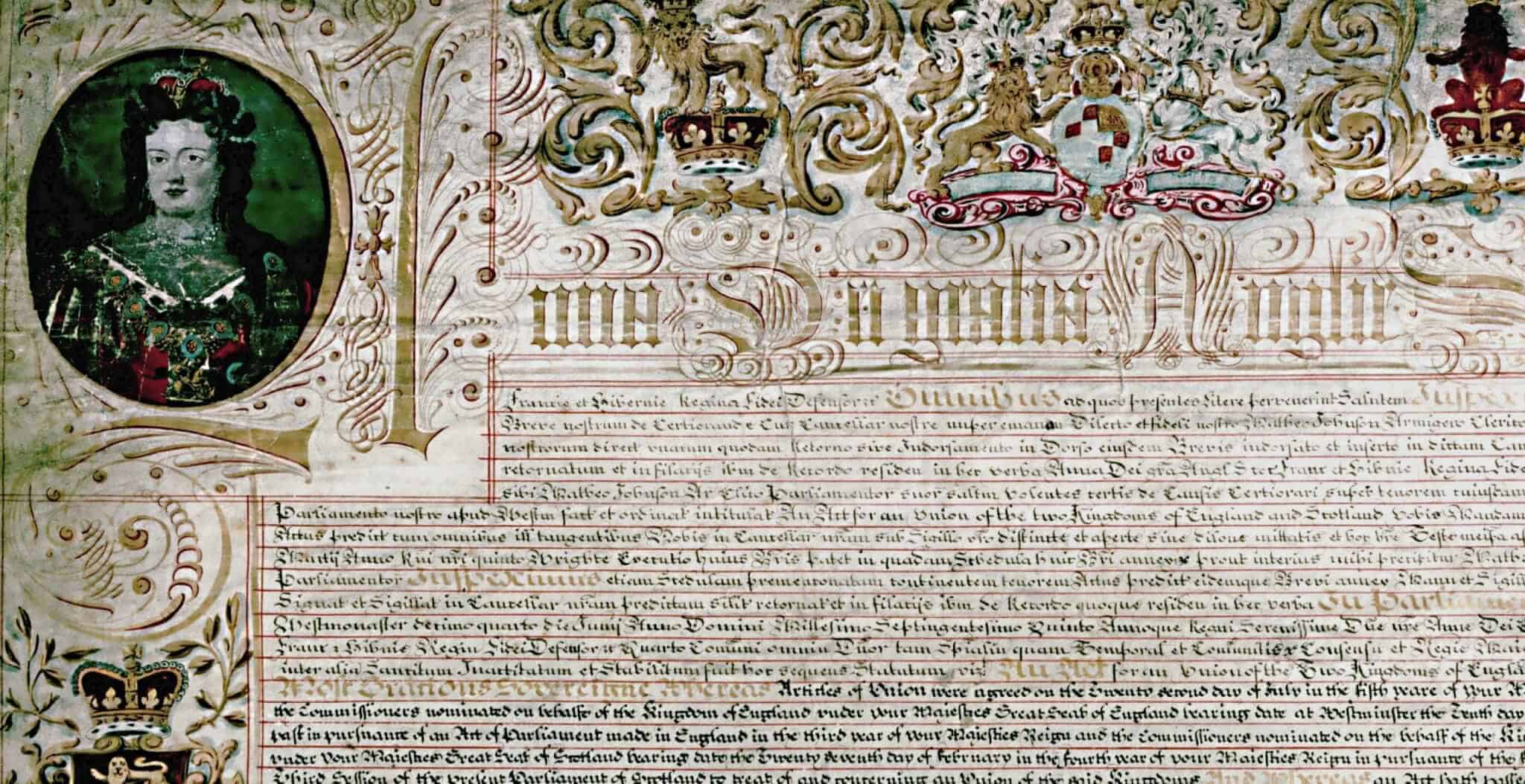

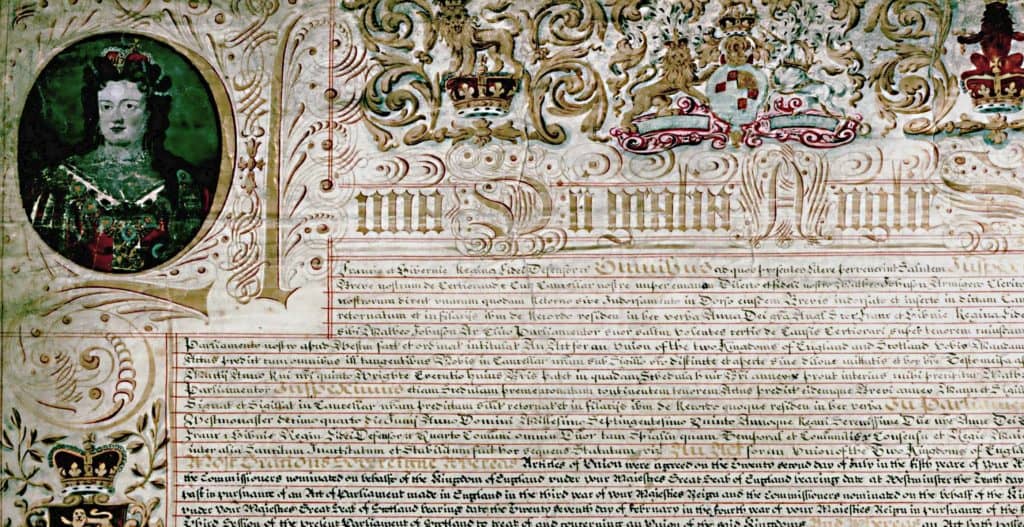

Only one ship returned out of the total of sixteen that had originally sailed. Only a handful survived the return journey. Scotland had paid a terrible price with more than two thousand lives lost. Together with the loss of the £500,000 investment the Scottish economy was almost bankrupted. It has been argued that the Darien Scheme crippled the country’s economy to such an extent that it triggered the dissolution of the Scottish Parliament and led to the 1707 Act of Union with England. Was this a mere coincidence, or had the English withdrawal from the scheme been deliberately engineered to ensure its failure?

Images from Glasgow University Library, Dept. of Special Collections