Singapore, city of silk shirts, colonial grandeur, Singapore Slings at The Long Bar in Raffles Hotel, peanut shells, Change Alley, merchant shipping and the infamous Merlion, not to mention the best chicken satay anywhere in the world. Nowadays the city is a melting pot of cultures, a haven for ex-pats and a centre of tourism. However, there is a lot more to this ex-British colony than its culinary expertise, financial finesse and adventurous nautical history.

This tiny sovereign island nation was the scene of the largest surrender of British-led forces ever recorded in history. Singapore is a sovereign island nation, sandwiched between Malaysia and Indonesia in South-East Asia. At the time, it was considered by the British as their Gibraltar in the Far East, assumed to be just as impregnable and certainly as valuable as it’s European counterpart. Singapore was, and indeed remains, the gateway to the rest of Asia. If you control Singapore, then you control a huge proportion of the Far East.

At the beginning of December 1941, on the same day that Japan was attacking Pearl Harbour half a world away, the Japanese simultaneously bombed the Royal Air Force bases to the north of Singapore on the Malay coast, thereby eliminating the Air Force’s ability to either retaliate or protect the occupying troops on the ground. Their tactics were shrewd and incredibly well thought out. Before a Japanese soldier set foot on Singaporean soil, Britain’s naval and aerial capabilities had both been destroyed. When the Navy responded by sending the battleship ‘Prince of Wales’ and the battle cruiser ‘Repulse’ at the head of a fleet of ships, both were torpedoed and sank into the tropical waters. This left Singapore defenseless to assaults from both air and sea. Britain and Singapore’s only hope was in the British Army and Commonwealth forces.

‘Prince of Wales’ and ‘Repulse’ under Japanese air attack, 10th December 1941

‘Prince of Wales’ and ‘Repulse’ under Japanese air attack, 10th December 1941There was still an expectation at this point that the attack would come from the sea. It was a much simpler way for the Japanese forces to attack, than sending troops through the treacherous jungle, mangroves and swamp that characterized the land. Over-estimating the defensive nature of the jungle was a grave mistake that left the British-led forces completely outmaneuvered. In fact, a sea attack was so expected that, at huge expense in the 1930’s, Singapore had been fortified with huge gun placements that pointed straight out to sea. Of course these defenses proved ineffectual in repelling an attack over land. The Japanese forces mandate for not taking prisoners also allowed a speed of attack for which the British were not prepared. Without having to stop, restrain and corral enemy troops, the attacking forces could move quickly over the ground.

The British commander at the time, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, had 90,000 men at his disposal. His forces consisted not only of British, but also Canadian, Indian and Australian forces. The fighting began in the north in Malaya. Here Percival’s troops were soon humiliated at the Battle of Jitra between the 11th and 12th December 1941. On January 31st 1942, overestimating the size of the enemy forces, the British retreated to Singapore, falling back over the causeway that separated it from the mainland. Meanwhile the Japanese swarmed south, some on stolen bicycles, through the jungle from Kota Bahru towards Singapore, which lay over 600 miles south.

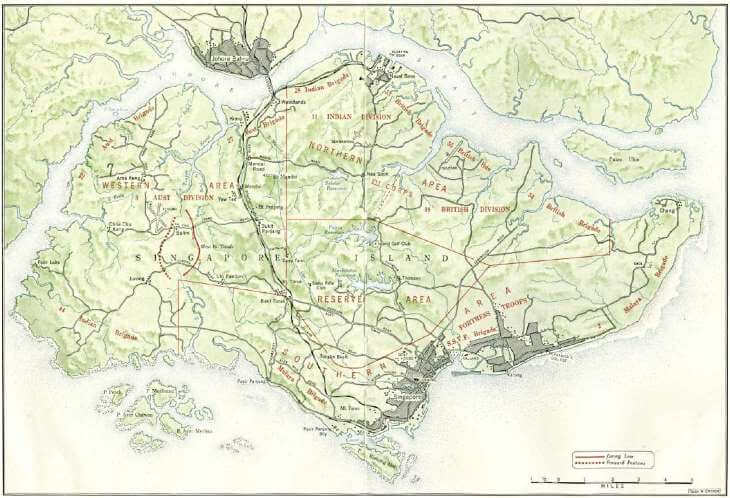

Map of Singapore showing dispersal of British troops, February 1942

Map of Singapore showing dispersal of British troops, February 1942Percival, aware of the seemingly unstoppable Japanese pursuit, ordered his men to spread over 70 miles in order to face the oncoming onslaught. This proved a fatal mistake. With his forces, although far superior in number, spread so thinly, they were unable to repulse the Japanese forces and were completely overwhelmed. The leader of the Japanese forces, Yamashita attacked with only around 23,000 troops and on 8th February 1942, they entered Singapore.

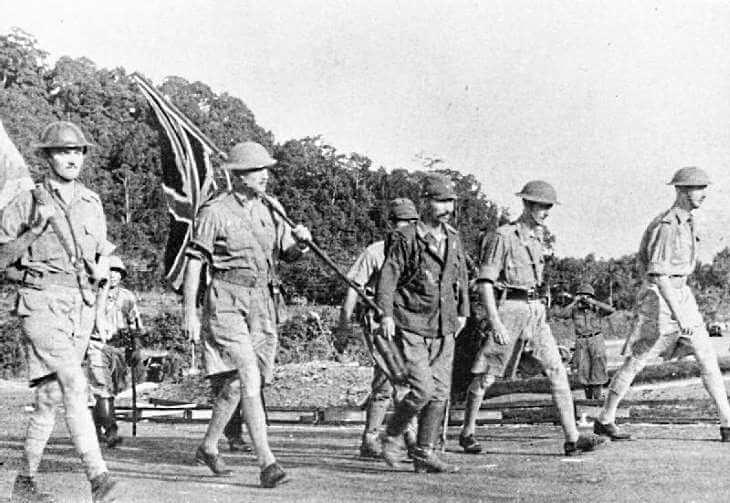

On their way to surrender to the Japanese. Percival is far right

On their way to surrender to the Japanese. Percival is far rightJust seven days later, on 15th February 1942 Singapore fell to the savagery and tenacity of the Japanese army. Percival surrendered in a futile attempt to prevent further loss of life. An estimated 100,000 people in Singapore were taken prisoner, some 9,000 of whom were said to go on to die building the Burma-Thailand railway. The estimated deaths of those under Japanese control in Singapore range from a Japanese estimate of 5,000 to that of the Chinese of 50,000. Whatever the exact figure, it is undeniable that thousands lost their lives under Japanese occupation.

Percival surrenders to the leader of the Japanese forces Yamashita (seated, centre). Percival sits opposite, between his officers.

Percival surrenders to the leader of the Japanese forces Yamashita (seated, centre). Percival sits opposite, between his officers.The worst defeat of all time for British-led forces, it was not only lives that were lost but the idea of European superiority in war. Churchill himself was said to remark that the very honour of the British Empire was at stake in Singapore. That honour and reputation was undoubtedly tarnished. However, arguably not as much as that of the Japanese troops who occupied Singapore. During the fighting and immediately afterward, civilians were murdered, enemy soldiers decapitated, prisoners burnt alive, hospital patients slaughtered where they lay. The savagery was truly shocking to British colonial troops, especially those who, until this battle, had never been in action. What followed was a brutal occupation and massacre of the local Chinese population. Those prisoners that survived and who were interned as Prisoners of War were subjected to three years of pain and torment: many British, Australian and Canadian troops never made it back to their homes, even after the war ended.

By Ms. Terry Stewart, Freelance Writer.