English history is full of powerful queens who have each left their mark on our culture with their strong and vibrant lives. Women like Elizabeth I and Mary I, who ruled in their own right, as well as famous wives of kings such as Eleanor of Aquitaine or Margaret of Anjou, are inspirational and respected historical names.

Yet women are far more likely to be forgotten in the swell of history. Despite their importance at the time, their impact is often snubbed by historians in succeeding centuries.

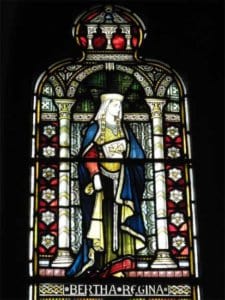

Queen Bertha of Kent, Princess of the Franks, is such a woman, whose influence on Britain could be, but should not be, overlooked.

Bertha was daughter of Charibert I, King of Paris, and was born around 539 AD. A Christian, she married Ethelbert, the pagan King of Kent, and moved to Canterbury in around 580 AD. Ethelbert is a name that is more readily recognised than that of his wife. Ethelbert is famously remembered for being the first Anglo-Saxon King to convert to Christianity.

Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, described how Ethelbert was distrustful at first of the mission and met them under the open sky in case they used sorcery to convert him immediately.

Despite this mistrust, Ethelbert did allow the mission to settle in Canterbury and permitted them to preach, although he was not converted straight away. The tradition goes that it was on Whitsunday that Ethelbert declared himself a Christian and was baptised.

Augustine was appointed the first Archbishop of Canterbury in 597 AD. His mission and its success in converting the influential Ethelbert is officially considered to be the birth of Christianity in Britain.

Of course, the actual story is a little more nuanced.

Christianity arrived in Britain with the Romans as far back as the 1st Century, although at that time it was only one of many religious cults. When Ethelbert officially converted, many of his people followed his example, although equally it is thought that a lot of the English were less than enthused by the transition. Even Ethelbert’s own son, Eadbald, was resistant to the religion and reverted to paganism for a time before reconverting to Christianity.

More importantly, Bertha’s place in the introduction of Christianity to Britain is often overlooked.

Ethelbert married Bertha to build an alliance with her father, the powerful King of the Franks, and a part of that deal was for Bertha to be allowed to practise her Christian faith. Bertha brought her own chaplain Liudhard with her when she came to England and she set up St. Martin’s Church as her own private chapel.

St Martin’s Church, Canterbury

St Martin’s Church, CanterburyAugustine used St. Martin’s as his headquarters before the building of St. Augustine’s Abbey and Canterbury Cathedral. The Cathedral and Abbey may be more ostentatious but St. Martin’s is still the first church founded in England and the oldest parish church in continuous use. Without Bertha’s base, modern Canterbury might not have its World Heritage Site.

Bertha has left a quiet but indelible mark on the landscape of Canterbury. Still visible within Canterbury’s city wall is the Queningate, named so because that was where Bertha passed on her way to worship at St. Martin’s Church. Canterbury celebrates her with a statue in Lady Wootton’s Gardens, which stands facing a similar statue of her husband.

She should be remembered as such.

Cat Dennis lives in Canterbury after moving to the area to study, drawn by its rich history and culture. She completed her Medieval History MA in 2016, with a focus on female saints. If you liked my work, please check out my blog on heritage and folklore: https://curiositydamsel.wordpress.com/