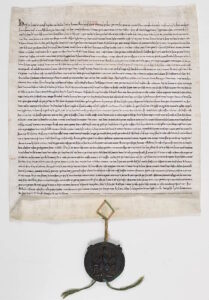

The 1259 Treaty of Paris is an often overlooked yet seminal agreement in medieval history that set the Crowns of France and England on the path to the Hundred Years War.

The initial significance of the Treaty was to bestow peace upon France and England, whose ruling houses had been in conflict for several generations. The king of France, Saint Louis IX, was the principal architect. He was arguably the most powerful and respected ruler in Christendom and had bested his fellow signatory to the treaty in battle. Henry III on the other hand stood at the helm of a monarchy whose fortunes had been in decline since the dawn of the 13th century. Moreover Henry did not even have control over the country he supposedly ruled, constrained as he was by the Provisions of Oxford forced upon him in the previous year.

The century prior to the peace of 1259 had seen the king of England acquire land holdings in France greater than that ruled directly by the French king himself, under Henry II and his wife Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine. By the time of Henry III’s reign however, the English king had seen Normandy, Anjou, Maine and Poitou seized by the French crown, with a shrunken Aquitaine clinging to the south-western coast as Henry’s last remaining slice of French territory. Henry had harboured dreams of restoring these lands. He led two unsuccessful campaigns in Poitou in 1230 and 1242, the latter ending in his army being driven away to Bordeaux by a force led by Louis himself.

The English king never managed to muster another invasion force, and so it was that Henry came to grudgingly accept his inability to change the status quo in France. In any case, Henry’s baronial council – dominated by Simon de Montfort – strongly favoured a settlement with France, thus forcing England’s king to the negotiating table.

The Treaty saw Henry relinquish the claims of the English crown to Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Touraine and Poitou, thus destroying for good the dreams of a restoration of the Angevin Empire.

The Treaty’s deepest importance for the future however lay in its provisions relating to the territory of Gascony on the south-western coast, centred on the city of Bordeaux. Gascony would not only be retained by the King of England, but Louis ceded neighbouring French territories to expand the duchy. This provoked indignation amongst members of Louis’ council, who lamented that ‘Your Majesty is needlessly throwing away the land you are giving to the king of England’. Louis’ apparent generosity seems to have been motivated in part by his earnest desire to come to peace with his Christian brother-in-law. However, there was another side to the coin.

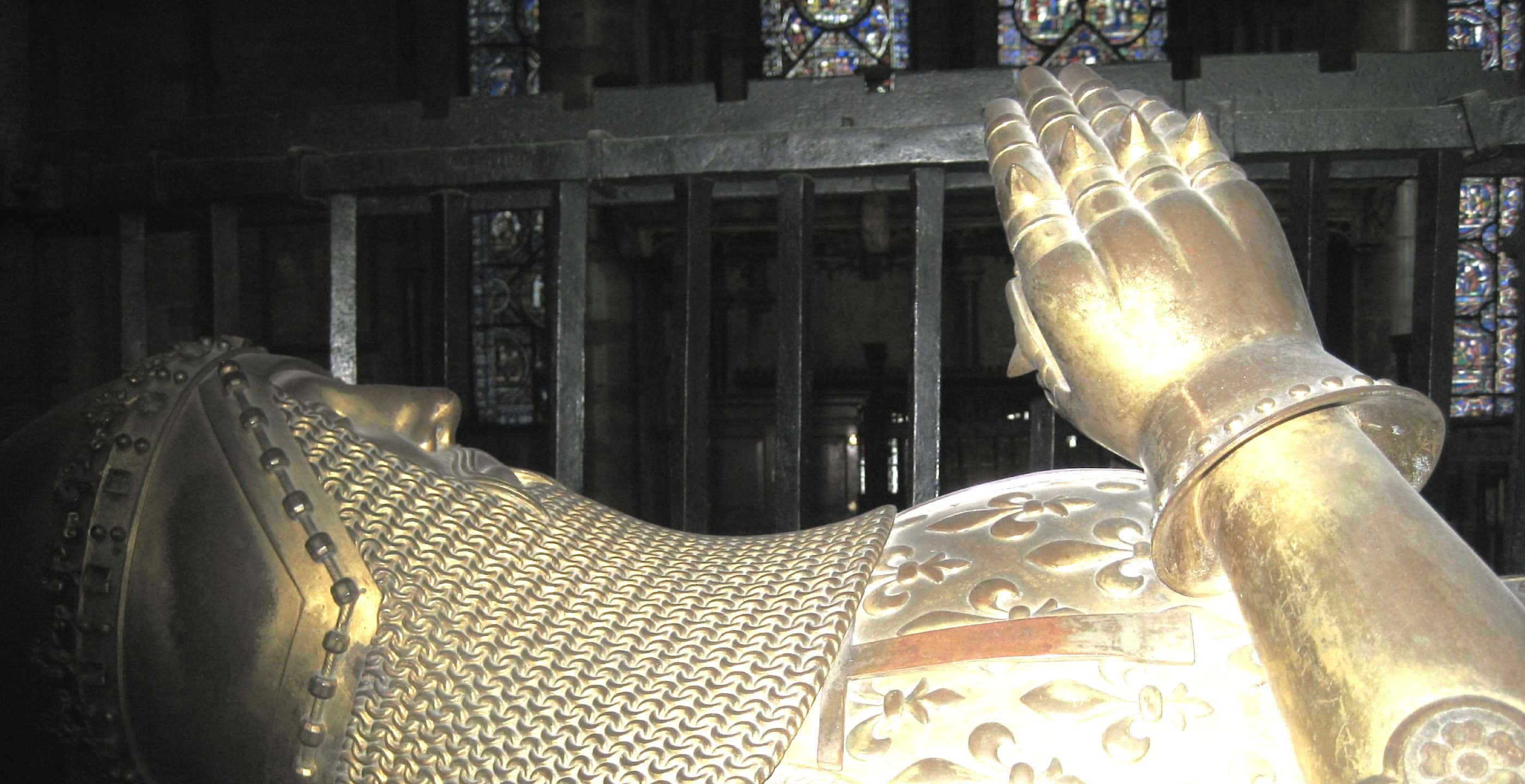

The king of England was to rule this expanded duchy of Gascony as a vassal of the French king, and was to perform homage for possession of the royal fiefdom. Technically this had always been the relationship between the French and English kings, since 1066 when the latter became Dukes of Normandy as well as Kings of England. But this had been little more than a legal apparition. English kings had long disputed the performance of homage and failed to comply – Jonathan Sumption insists that prior to 1259 the dukes of Aquitaine ‘had acknowledged no superior on earth’ (Trial by Battle, pg. 72), and after the confiscation of their French lands by Philip Augustus in the early 13th century the English kings repudiated any relationship at all with the French monarch.

The peace of 1259 solidified the grip of the English king on Gascony whilst at the same time deeply undermining it. It expanded the duchy but bound its ruler to a bond of vassalage that made the king of England an inferior to the king of France in lands that had never been held by the Capetians. With this vassalage came an elaborate ceremony of homage in honour of the French king’s overlordship, performed as and when the latter requested. It also allowed the French king to demand military service from the Duke’s Gascon subjects, and, crucially, Gascons were able to appeal decisions made by the Duke-King to the French Crown and its Paris Parlement.

For the decades following 1259 French kings would use their new position as feudal overlord to erode the English king’s authority in Gascony. Gascon subjects were encouraged to appeal to the Parlement of Paris (the royal judicial body of France) against decisions made by the duke-king, undermining his legal authority. Moreover the performance of homage was a consistently thorny issue, with Philip IV and his successors frequently demanding the attendance of the English king at the French court to pledge their fealty, and threatening to confiscate the duchy if they did not show.

The treaty had satisfied no one. The French kings had been riding a wave of continuous territorial expansion and growth in power for over a century – at the expense of the Plantagenet dynasty. By making the English kings their vassal of an expanded Gascony the treaty had left the duchy of Aquitaine like the fruit of Tantalus to the French – their final victory hung just out of their reach, close enough for them to be tempted to reach for it. Meanwhile the Treaty left the English kings as substantial land holders in France, yet besmirched their royal dignity by their inferiority to the French king and exposed them to the latter’s attempts to reclaim it.

Perhaps the most important vice of the treaty was simply its lack of detail with regards to the territorial boundaries of the English-held lands. Louis and Henry perhaps hoped that these questions of territory would be resolved over time, however it brought heightened confusion to the region and left future rulers of France and England scrambling to assert their rights over the Gascon march lands.

With every tussle over the rights of the respective monarchs in the South-West the animosity between the kingdoms only grew. After one of these incidents in 1294 Philip IV announced the confiscation of Gascony from the English king, leading to a brief conflict and a return to the status quo in 1303. This presaged the very same manoeuvre by Philip VI that in 1337 would open hostilities of the Hundred Years War.

Tensions were thus present well before Charles IV of France died without an heir in 1328, the event that is commonly held as the seedbed of the Hundred Years War.

Philip VI’s succession as king of France in 1328 was essentially unchallenged. The young Edward III held a strong claim to be sure, through his mother Isabella, yet the French nobles would not seriously contemplate the English king taking the French throne. Edward III’s eventual claim of the throne did not take place until 1340, three years after the outbreak of the Hundred Years War, and was a calculation designed to bolster the war effort rather than the driving reason behind said war effort. By claiming the throne Edward provided a legal cover behind which French subjects allied to him could rally. Whether or not this claim became the central plank of the English war effort in the 15th century, it was not the original the cause of the conflict.

The Treaty of Paris should not be held as the sole cause of the Hundred Years War. The French and English kings were in conflict before this treaty, and the roots of their rivalry really originate in the Norman Conquest, were one forced to point to a single event of overriding importance. Nevertheless it might be useful to view the Treaty of Paris as similar in some ways to the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. They both came between two periods of intense conflict, and in attempting to defuse the first they reset the relationships between the warring states into a new, freshly antagonistic setting which only created more tensions for the future.

Calvin Hartley is a freelance history writer specialising in medieval and ancient European history.

Published: 14th November 2024