Just as the sun begins to set on the 5th January, so the coming of the Twelfth Night arrives, marking the last day of Christmastide and the coming of the Epiphany.

After counting twelve days since the arrival of Christmas Day, the season of festivities reaches its climax and is celebrated in many countries around the world.

In medieval England, the Twelfth Night was a time of celebration when presents were exchanged and a lavish display of food shared between loved ones, much like Christmas Day is celebrated today.

In Tudor England, the Twelfth Night revelries were taken very seriously, particularly amongst the upper classes who celebrated in style with pageantry, lavish banquets and games. Queen Elizabeth I had a designated gingerbread maker who constructed tasty treats in the form of her guests, whilst her father made sure to use the gardens at Greenwich Palace in order to accommodate hundreds of dishes which were to be served on the night. The centrepiece to these displays was the Twelfth Night cake.

The cake itself was laden with fruit and more akin to a bread texture than cake mixture. Within the cake, a tradition of including a large dried bean or pea within the mixture resulted in the person who discovered this hidden element becoming “king” or “queen” for the rest of the night.

Once the festive feast had been consumed, singing and merriment would dominate the rest of the night involving many centuries’ old traditions such as drinking wassail (punch) as well as singing door-to-door, much like modern day carol singers.

Records of the cake can be found in Samuel Pepys diary which describes the tradition of the fruit cake, paying close attention to who would receive the bean or pea and play at being the “king” or “queen”.

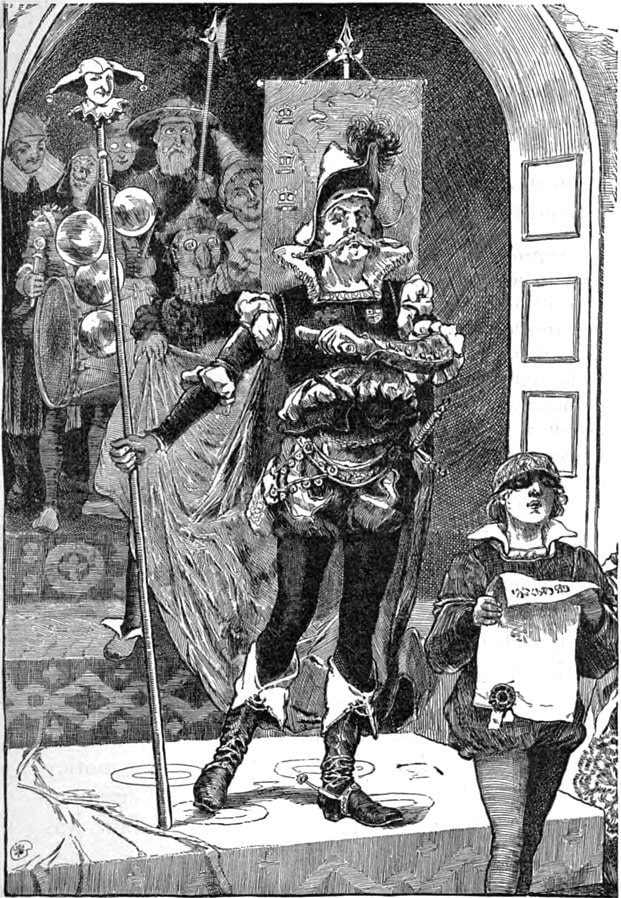

The origins of this tradition date back even further to the Roman era when the Lord of Misrule was appointed to organise games and light entertainment. The recipient of the bean was to be anointed “Lord of Misrule” or “king” whereby the celebratory revelries would get into full swing.

Such a tradition was popular at the beginning of the Tudor period as King Henry VII was said to have appointed an “Abbot of Unreason” (also known as Lord of Misrule) at his celebrations.

Throughout the medieval period and for many centuries, the Twelfth Night cake became a mainstay in festive gatherings. In later centuries the cake decorations became more elaborate with sugar work and royal icing.

The Twelfth Night cake was the essence of luxury as the shop windows would have been filled by these exquisitely decorated treats tempting those fortunate enough to be able to afford the scrumptious festive delicacy.

Moreover, it instigated competition between fellow bakers who were keen to display their culinary skills.

The cake itself had originally started out as a type of bread and turned into a leavened fruit cake with added ingredients of festive spices such as clove and nutmeg and for those with a penchant for a tipple, a slither of brandy to add to its allure. Its body and texture bore a close resemblance to its continental cousin, the Italian panettone.

In 1795, the cake began to make an appearance in the world of theatre as it was provided during the festive celebrations at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London. The tradition would continue for the company in residence to consume cake and punch by all those partaking in the merriment of the day.

Sadly, the observance of Twelfth Night diminished over time, beginning with the impact of the Reformation which resulted in Epiphany celebrations becoming less frequently observed. Whilst the impact of growing Protestantism effected religious festivities, the popularity of the cake endured into the eighteenth century, whilst also continuing to evolve with the changing face of religion, festivities and traditions of cake-making.

The cake itself which had begun more as a bread-like state, brioche in style soon changed with the addition of other ingredients. In time, the plum cake became a more popular choice on the Christmas menu, whilst the bean or pea included within the cake was replaced by smaller trinkets often in silver.

By the eighteenth century, with new styles and discoveries in baking and decorating, the cakes became more elaborately adorned.

By the turn of the next century and the advent of a new era under the reign of Queen Victoria, the style of celebrating Christmas in England had evolved completely with new traditions such as the Christmas tree brought over from the German influence of Prince Albert.

Whilst the Twelfth Night cake did not disappear from English Christmas tables, instead it transformed into what is more familiar today, the Christmas cake and eventually, the ubiquitous Christmas pudding.

The Victorians established many Christmas traditions which persist today and sadly the Twelfth Night cake presence at the dinner table diminished.

The Twelfth Night cake like its more modern replacement, the Christmas pudding, had a long and enduring history on the tables of many a Christmas feast demonstrating how much history is displayed in the festive celebrations and food we consume. Much like our ancestors, the food and fashions evolved with our palates and today an array of puddings and desserts reflects the ever-changing and evolving history of food as an integral part of our culture.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 16th August 2023.