The town of Moffat is one of south west Scotland’s gems. Much of its architectural charm is the legacy of its economic history. The woollen industry, the Georgian coaching network, the development of the railways, and a passion for healing spas have all played their part in Moffat’s success. Today, this bustling town situated in the lovely hills of Upper Annandale is better-known for its hospitality, walking paths, golden eagles, and the celebrated Moffat Toffee Shop, an essential stop on any traveller’s itinerary.

There’s also a park with a boating lake where the visitor can parade serenely on board a dragon, unicorn, or swan boat. Plus, a delightful volunteer-run museum which tells the remarkable history of Moffat, including the discovery of one of Scotland’s oldest archery bows, a major find dating back some 6,000 years.

Moffat is a town with a great sense of its own history, including the grimmer aspects. In one famous incident a mail coach was trapped in the snow. The driver, John Goodfellow, and the guard, James McGeorge, attempted to battle through the snow to deliver the mail using the mail coach horses, but were overcome by the conditions and died as a result. The horses survived.

The nearby hollow in the hills known as the Devil’s Beef Tub was the place where cattle stolen by the infamous border reivers, no strangers to violence, were hidden away. However, by far the most dramatic and horrifying episode to shock this rural town was the crime that became known as the Moffat Ravine Murders. The investigation of the killings of Isabella (“Belle”) Ruxton and Mary Rogerson led to global notoriety and ultimately great advances in forensic science.

And that’s why, in spring 2023, a tiny phial of dead maggots was transported with unusual care from the Natural History Museum in London to Moffat Museum. The maggots were an essential element of the museum’s exhibition, “The Moffat Ravine Murders – the Birth of Modern Forensics”, curated by Janet Tildesley.

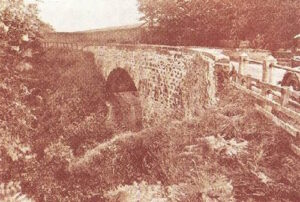

For Moffat, the story began on the morning of Sunday 25th September 1935. Some regular visitors to the town, Susan Johnstone and her mother, were walking near one of Moffat’s many beauty spots, Gardenholm Linn. Through the picturesque linn, a Scots word comprehensively describing a waterfall, stream, and ravine, ran a very minor tributary of the River Annan. The women paused on the Gardenholm Bridge. As Susan glanced down into the depths of the gorge, she spotted a bundle, from which she saw a human arm hanging out.

Returning to the hotel from their walk in a state of shock, hoping that they were wrong in their deduction, they asked Susan’s brother Alfred to investigate further. Taking a friend who lived locally along with him, Alfred returned to the linn where the two scrambled down the steep banks to the stream to see if they could find out more.

The bridge at Gardenholme Linn, nr. Moffat. Pictured at the time of the discovery of the dismembered bodies of Isabella Ruxton and Mary Jane Rogerson.

They were horrified to discover not only an arm but also several more body parts wrapped in newspaper and material. The local constable James Fairweather was quickly summoned, along with support from Dumfries in the form of Sergeant Robert Sloan. The search soon revealed further gruesome finds; two heads, two arms, a thighbone and various pieces of flesh and skin. The tops of the fingers and thumbs had been cut away. By the time the rest of the body parts were assembled, there were 70 of them. Only one of the torsos was present and the other was never found. The parts had been wrapped in newspaper and fabric. Part of a child’s romper suit had been used to wrap round one of the heads.

It was soon clear that whoever had committed the murders had intended to disfigure and destroy the remains of the two bodies so comprehensively that they could never be identified. Teeth had been removed, the lips, eyes, and other distinguishing features had been cut away, and in removing the tops of the fingers and thumbs, the perpetrator had evidently hoped that no fingerprint identification could be made. The mutilated state of the bodies, and the fact they had been discarded in a remote location, suggested that the culprit thought the crime was insoluble.

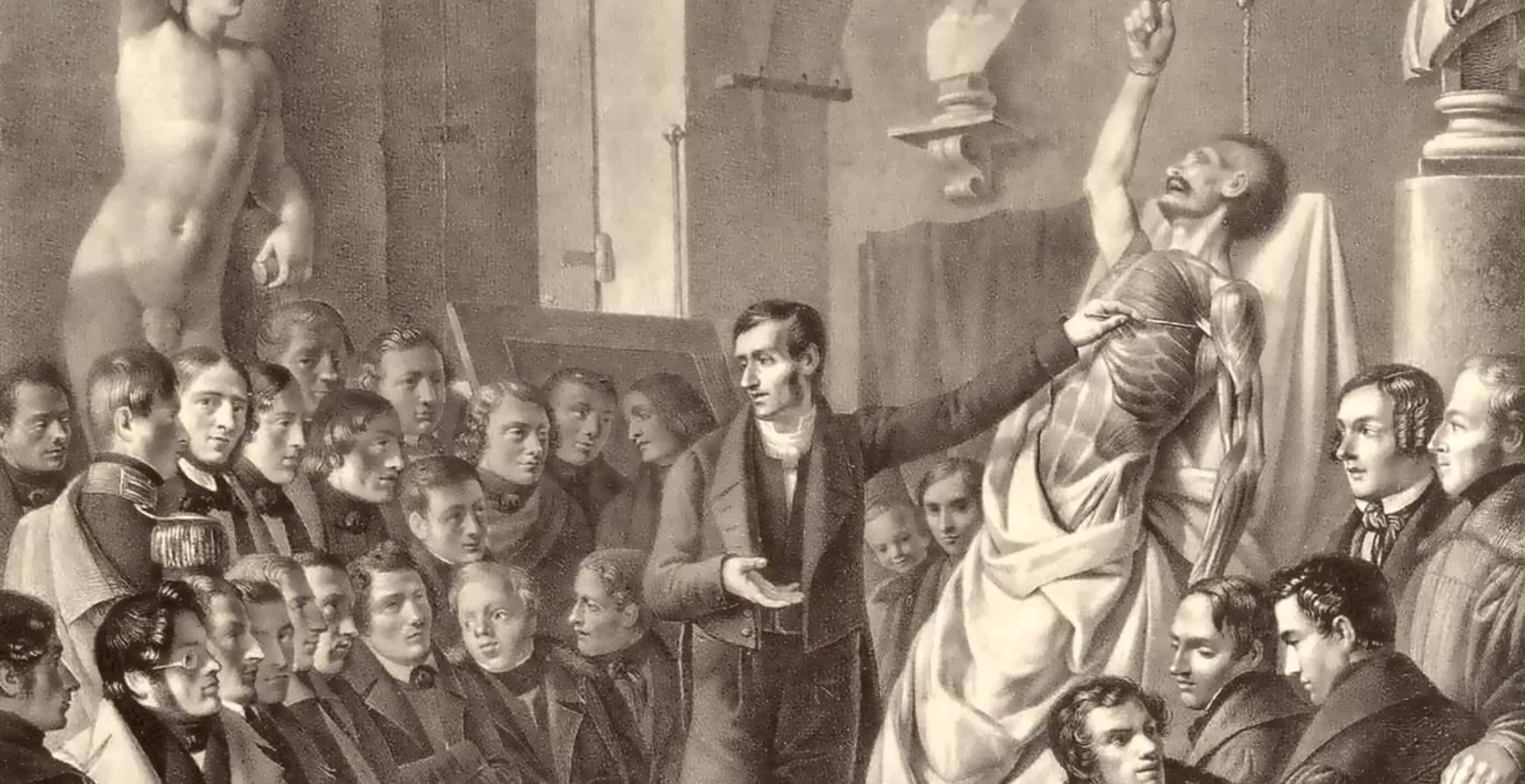

However, the criminal hadn’t reckoned on one of the most extraordinary professional gatherings of police and forensic specialists ever to assemble to tackle a crime of violence. The head of the forensic team was John Glaister, Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Glasgow. The other team members included anatomist James Couper Brash, and Sir Sydney Smith, the eminent pathologist who held the Regius Chair of Forensic Medicine at Edinburgh University, where much of the lab work on the remains was carried out.

Local police officer Sergeant Robert Sloan from Dumfries played a key role in ensuring the evidence was safeguarded in the immediate aftermath of the discovery. He made certain the crime scene was secure so that police officers from Glasgow could photograph and collect the body parts for further investigation. This made the subsequent detailed forensic investigation possible. It was an investigation of the highest standards, with some of the leading police officers in Britain.

Glasgow Detective Lieutenants William Ewing and Bertie Hammond were essential to the investigation. Bertie Hammond’s photographic and fingerprint work would secure much of the evidence that would bring the killer to justice.

Bertie Hammond was a Sergeant in the Fingerprint Department of Sheffield City Police at a time when Percy Sillitoe, introducer of police phone boxes to the Sheffield force, was the Chief Constable there. In 1931 when Percy Sillitoe was appointed Chief Constable of Glasgow he offered Sergeant Hammond the job of leading Glasgow’s Fingerprint Department and Photographic Department. It meant a promotion for Bertie Hammond to Detective Inspector, and then Detective Lieutenant in charge of the new Glasgow Department.

Detective Lieutenant Hammond was able to develop a new fingerprint technique to identify the bodies, as the fingers had been deliberately mutilated. He did this by burning his own fingers and removing the top layer of skin to show that even when this was damaged, fingerprints could be taken. Detective Lieutenant Bertie Hammond would eventually be awarded the British Empire Medal for Meritorious Services.

In the initial stages, the forensic specialists and police were faced with the problem of identifying which body parts belonged to which body, whether there were two bodies only, and whether they were male or female. It was finally confirmed that there were two bodies, both women, one in her late teens or early twenties and the other in her forties.

One of the key forensic developments that came about as a result of the investigation into the Moffat Ravine murders (which for obvious reasons due to the state of the bodies, also became known as the Jigsaw Murders) was the use of entomological knowledge to establish the time of death based on the life-cycle of maggots. The large number of bluebottle fly maggots (Calliphora vicina) found on the remains, and the stage of their life-cycle, suggested that death had taken place 12 to 14 days previously. This was the first time entomology had been used in this way in UK forensic work, and the pioneer in this case was Alexander Gow Mearns, an entomologist and public health specialist at the University of Glasgow.

Another major clue was identifying one of the newspapers as a limited edition paper circulating in Morecambe, Lancashire. It was also clear that whoever had carried out the mutilation – and in all probability, the murders – had, in Glaister’s words, “definite anatomical knowledge”. This might suggest the surgical knowledge available to a doctor or other medical professional.

Dr. Buck Ruxton

In the town of Lancaster, not far from Morecambe, a young doctor of Parsi and French heritage had established a good reputation for his skills and was maintaining a successful practice. His name was Buck Ruxton, and he knew Scotland well as he had spent part of his studies there. His partner, or common-law wife as the term was then, Isabella Kerr, was Scottish. They had frequently travelled up to Edinburgh to visit her relatives and knew the route to Moffat from Lancaster well.

Around the time of the discovery, when the sensational story hit the headlines globally, Ruxton was telling friends and acquaintances that his wife and the children’s nanny, Mary Jane Rogerson, were both missing. His stories were inconsistent; sometimes he said they had gone to Scotland, at another time to London, that Mary was pregnant and having an abortion, or that Isabella Kerr, his “beloved Belle” had left him to set up a football pools business. He was agitated and the three children, his “wee mites” were frequently left in the care of friends and neighbours while he attended to other business. There was evidence of burning material at his home, and the charwoman who cleaned for him noted blood in staggering amounts in the carpets she washed, and observed that the bath in one of the bathrooms was stained a curious colour. He had a cut on his hand, and his tales about how he had done this varied too.

Buck Ruxton was esteemed and even loved by his patients. However, his relationship with Isabella had always been fraught. He frequently accused her of infidelity and exhibited controlling behaviour. Isabella said she would commit suicide and attempted to carry this out on several occasions. She went to the police for help more than once. However, there were always reconciliations, and later in court he would say “If I may put it in proper English, we could not live with each other and we could not live without each other.”

Within a short time, therefore, the task for the experts was to prove that the bodies were indeed those of Isabella and Mary. The maggots on the remains suggested that death had occurred around the time the women were presumed to have gone missing. As well as developing new fingerprinting techniques, the forensic specialists also used pioneering skull photography developed by photographer Cecil Thomas. After many long hours of experimentation, the skull of Isabella Ruxton was placed at an angle and photographed, then overlain as a photo-transparency over a photograph of her. Isabella’s distinctive facial structure and features revealed in the photograph matched those of the skull. Thus, the technique of photographic superimposition was one of the successful outcomes of the investigation.

The investigators also made casts of the feet of the bodies, and fitted shoes belonging to Isabella and Mary to show how good a match they were. The researchers found evidence that “Body no. 2”, that of Isabella, had worn a denture that matched her dental records. No potential avenue to identification was overlooked. The romper suit was discovered to have been a gift given to Mary by a friend with whom she was staying in the Lake District, intended for Ruxton’s son Billy-Boy. The investigators deduced that these were their bodies, that Isabella had been strangled, beaten and stabbed, and that Mary Rogerson had been killed for witnessing the crime or to prevent her finding out.

Dr Buck Ruxton was arrested on 12 October 1935. Initially he was charged with the murder of Mary Jane Rogerson the following day. After this the investigators had unhindered access to his house, 2 Dalton Square, Lancaster. Once again led by Detective Lieutenant Hammond, officers began to search the house for fingerprints they could match to the prints they had obtained from the person they now believed to be Mary Rogerson. They also discovered extensive evidence of bloodstaining at the Dalton Square house, particularly in the bathroom and on the stairs.

Here the forensic and police teams really showed their dedication and skill. There was so much evidence to be examined that it would require dedicated lab work on a grand scale, but the labs were in Glasgow. The solution was to dismantle parts of the house and reconstruct it in Glasgow, including Ruxton’s bathroom. Sergeant Frederick Harrison made a scale model of the Ruxton’s house that would subsequently be used in court.

On 5 November 1935, Ruxton was also charged with the murder of Isabella Kerr. The evidence pointed to the murders taking place on 15 September 1935. Ruxton vehemently denied the murder of either woman, and continued to be agitated and emotional. His trial took place in March 1936 at Manchester Assizes. Despite the full horror of the crime and its aftermath, Ruxton continued to draw a great deal of support and sympathy, particularly from his former clients.

He was represented in court by Norman Birkett KC. Birkett was a formidable legal presence, a man who had already apparently pulled off the impossible by convincing a jury despite overwhelming evidence that Toni Mancini had not been responsible for a murder in Brighton. The sole defence available to Birkett in Ruxton’s case was the contention that the bodies were not those of Isabella and Mary, but of two other unknown individuals, thus the forensic evidence was flawed.

Buck Ruxton continued to deny the charges throughout the trial, during which he was questioned by both defence and prosecution. He was found guilty on Friday 13 March 1936 and sentenced to death. His appeal was denied by Court of Appeal on 27 April. Such was the support for Ruxton that a petition of more than 10,000 signatures had been raised calling for clemency.

Buck Ruxton was hanged for his crimes on 12 May 1936, at HM Prison Manchester, better known to the public as Strangeways. He had given the News of the Word newspaper his confession to the crimes, to be published after his death. His executioner was Thomas Pierrepoint, uncle of the more famous hangman Albert Pierrepoint, Britain’s last executioner.

Ruxton’s three children with a maid

The descendants of the Moffat folk who were involved in investigating the murders in their early stages – the local policemen, the doctors, and the ordinary people of the town – still recall the sense of horror invoked by the discovery of the bodies. Perhaps the real victims of this extraordinary crime were Ruxton’s own “poor wee mites”, consigned to Parkside Children’s Home, Lancaster during the trial, of whom very little is known subsequently. However, H. Montgomery Hyde, Norman Birkett’s biographer, maintained that Birkett “did go to considerable trouble afterwards to arrange for the care and education of the murderer’s three orphaned children”.

It is to be hoped this was the case. According to Jeremy Craddock, author of a book on the case (The Jigsaw Murders: The True Story of the Ruxton Killings and the Birth of Modern Forensics) the children were subsequently put under a protective cloak of secrecy which will not be lifted until 2035. He confirms that Birkett worked “discreetly” to help them.

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published 7th August 2023