Wessex, also known as the Kingdom of the West Saxons, was a large and influential Anglo-Saxon kingdom from 519 to 927AD. From its humble beginnings through to the most powerful kingdom in the land, we trace its history from Cerdic, the founder of Wessex, through to his distant descendants Alfred the Great and Æthelstan who were responsible for defeating invading Viking hordes and uniting Anglo-Saxon England under a single banner.

Cerdic c. 520 to c. 540

As with many of the early Anglo-Saxon kings, little is known about Cerdic other than that written in the 9th century Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. According to the Chronicles, Cerdic left Saxony (in modern day north-west Germany) in 495 and arrived shortly afterwards on the Hampshire coast with five ships. Over the next two decades, Cerdic engaged the local Britons in a protracted conflict and only took the title of ‘King of Wessex’ after his victory at the Battle of Cerdic’s Ford (Cerdicesleag) in 519, some 24 years after arriving on these shores.

As with many of the early Anglo-Saxon kings, little is known about Cerdic other than that written in the 9th century Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. According to the Chronicles, Cerdic left Saxony (in modern day north-west Germany) in 495 and arrived shortly afterwards on the Hampshire coast with five ships. Over the next two decades, Cerdic engaged the local Britons in a protracted conflict and only took the title of ‘King of Wessex’ after his victory at the Battle of Cerdic’s Ford (Cerdicesleag) in 519, some 24 years after arriving on these shores.

Of course, it is worth remembering that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles were written around 350 years after Cerdic’s supposed reign and therefore its accuracy should not be taken as verbatim. For example, ‘Cerdic’ is actually a native Briton name and some believe that during the last days of the Romans, Cerdic’s family were entrusted with a large estate to protect, a title known as an ‘ealdorman’. When Cerdic came to power he was then thought to have taken a rather aggressive approach towards the other ealdormans in the region, and as a consequence started to accumulate more and more lands, eventually creating the Kingdom of Wessex.

Cynric c.540 to 560

Described as both the son and grandson of Cerdic, Cynric spent much of his early years in power trying to expand the Kingdom of Wessex westwards into Wiltshire. Unfortunately he came up against fierce resistance from the native Britons and spent most of his reign attempting to consolidate the lands that he already held. He did manage some small gains however, namely at the battle of Sarum in 552 and at Beranbury (now known as Barbury Castle near Swindon) in 556. Cynric died in 560 and was succeeded by his son Ceawlin.

Ceawlin 560 to either 571 or c. 591

By the time iof Ceawlin’s reign, most of southern England would have been under Anglo-Saxon control. This was reinforced by the Battle of Wibbandun in 568 which was the first major conflict between two invading forces (namely the Saxons of Wessex and the Jutes of Kent). Later conflicts saw Ceawlin focus his attention back to the native Britons to the west, and in 571 he took Aylesbury and Limbury, whilst by 577 he had taken Gloucester and Bath and had reached the Severn Estuary. It is around this time that the eastern portion of Wansdyke was built (a large defensive earthwork between Wiltshire and Bristol), and many historians believe that it was Ceawlin who ordered its construction.

The end of Ceawlin’s reign is shrouded in mystery and the details are unclear. What is known is that in 584 a large battle took place against the local Britons in Stoke Lyne, Oxfordshire.

It is strange that Ceawlin would win such an important battle and then simply retreat back towards the south. Instead, what is now thought to have happened is that the Ceawlin actually lost this battle and in turn lost his overlordship of the native Britons. This then led to a period of unrest in and around the Kingdom of Wessex, leading to an eventual uprising against Ceawlin in 591 or 592 (this uprising was thought to have been led by Ceawlin’s own nephew, Ceol!). This uprising would later be known as the Battle of Woden’s Burg.

Ceol 591 – 597

After deposing his uncle at the Battle of Woden’s Burg, Ceol ruled Wessex for the next five years. During this time there are no records of any major battles or conflicts, and little else is known about him except that he had a son called Cynegils.

Ceolwulf 597 – 611

After Ceol’s death in 597, the throne of Wessex went to his brother Ceolwulf. This was because Ceol’s son, Cynegils, was too young to rule at the time. Little is known about Ceolwulf , and the only reference to him in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles is that ‘he constantly fought and conquered, either with the Angles, or the Welsh, or the Picts, or the Scots.’

Cynegils (and his son Cwichelm) 611 – 643

After Ceolwulf’s death in 611, the throne of Wessex fell to Ceol’s son Cynegils (pictured to the right) who was previously too young to inherit the throne. Cynegils’ long reign started with a great victory over the Welsh in 614, but the fortunes of Wessex were soon to take a turn for the worse.

After Ceolwulf’s death in 611, the throne of Wessex fell to Ceol’s son Cynegils (pictured to the right) who was previously too young to inherit the throne. Cynegils’ long reign started with a great victory over the Welsh in 614, but the fortunes of Wessex were soon to take a turn for the worse.

Concerned about the rise of Northumbria in the north, Cynegils ceded the northern half of his kingdom to his son, Cwichelm, effectively creating a buffer state in the process. Cynegils also forged a temporary alliance with the Kingdom of Mercia who were equally concerned about the growing power of the Northumbrians, and this alliance was sealed by the marriage of Cynegils’ youngest son to the sister of King Penda of Mercia.

In 626, the hot-headed Cwichelm launched an unsuccessful assassination attempt on King Edwin of Northumbria. Rather annoyed by this, Edwin subsequently sent his army to confront Wessex and both sides clashed at the Battle of Win & Lose Hill in the Derbyshire Peak District. With the Mercians at their side, Wessex had a far larger army than the Northumbrians but were nevertheless defeated due to poor tactics. For example, Northumbria had dug into Win Hill and when the Wessex forces started moving forward, they were met by a barrage of boulders that had been rolled from above.

This was a humiliating defeat for both Cynegils and Cwichelm, and they subsequently retreated back within their own borders. The following years saw the Mercians take advantage of the weakened Wessex by taking the towns of Gloucester, Bath and Cirencester. To stop a further Mercian advance, it is thought that the western portion of Wansdyke was built by Cynegils during this time.

The final blow came in 628 when Mercia and Wessex clashed at the Battle of Cirencester. The Mercians were overwhelmingly victorious and took control of the Severn Valley and parts of Worcestershire, Warwickshire and Gloucestershire. As a result Wessex was now considered a second rate kingdom, although a truce was made with Northumbria in 635 which helped it to at least maintain its own borders.

Cynegils eventually died in 643 and his mortuary chest can still be seen in Winchester Cathedral today.

Cenwalh 643 – 645

King Penda of Mercia 645- 648

Cenwalh 648 – 673

Cenwalh was Cynegils youngest son and had previously been married off to King Penda of Mercia’s (pictured to the right) sister in order to seal an alliance between the two kingdoms. However, upon succeeding to the throne in 643, Cenwalh decided to discard his wife and remarry a local woman called Seaxburh, much to the annoyance of King Penda.

Cenwalh was Cynegils youngest son and had previously been married off to King Penda of Mercia’s (pictured to the right) sister in order to seal an alliance between the two kingdoms. However, upon succeeding to the throne in 643, Cenwalh decided to discard his wife and remarry a local woman called Seaxburh, much to the annoyance of King Penda.

‘…for he put away the sister of Penda, king of the Mercians, whom he had married, and took another wife; whereupon a war ensuing, he was by him expelled his kingdom…’

As a result, Mercia declared war on Wessex, drove Cenwalh into exile for three years, and took control of his lands. In essence, Wessex had become a puppet state of Mercia.

Whilst in exile in East Anglia, Cenwalh converted to Christianity and when he finally managed to reclaim the throne of Wessex in 648, he commissioned the first ever Winchester Cathedral.

Little else is known about the remainder of Cenwalh’s reign as most written texts covering this time period are focused around Mercian history.

Seaxburh 673 – 674

Seaburgh, wife of Cenwalh, succeeded to the throne after the death of her husband in 673 and was the first and only queen to ever rule over Wessex. However it is now thought that Seaxburh acted more as a figurehead for a united Wessex, and that any real and executive power was held by the various sub-kings of the land.

Æscwine 674 – c. 676

Upon the death of Seaxburh in 674, the throne of Wessex fell to her son, Æscwine. Although the sub-kings of Wessex still held the real power during this time, Æscwine nevertheless rallied his kingdom in defence again the Mercians at the Battle of Bedwyn in 675. This was an overwhelming victory for the Wessex army.

Centwine c. 676 to c. 685

Centwine, uncle of Æscwine, took the throne in 676 although very little is known about his reign. It is thought that he was a pagan in his early years (whereas his predecessors had been predominantly Christian), although he did convert sometime in the 680s. He is also said to have won ‘three great battles’ including one against the rebellious Britons, although once again most of the power in Wessex during this time was held by the sub-kings.

It is widely believed that Centwine abdicated the throne in c. 685 to become a monk.

Cædwalla 659 – 688

Thought to be a distant descendant of Cerdic, and almost certainly hailing from a house of nobility, to say that Cædwalla had an eventful life would be an understatement! In his youth he was driven out of Wessex (perhaps by Cenwalh in an effort to expel troublesome sub-royal families) and by the time he was 26 he had gathered enough support to begin invading Sussex and building his own kingdom. During this time he also obtained the throne of Wessex, although it is not known how this feat was accomplished.

During his time as King of Wessex he suppressed the authority of the sub-kings in an effort to consolidate his own power, and then went on to conquer the kingdoms of Sussex and Kent, as well as the Isle of Wight where he is said to have committed acts of genocide and forced the local population to renounce their Christian faith.

In 688 Cædwalla turned to Christianity and subsequently abdicated after being wounded during a campaign in the Isle of Wight. He spent his last few weeks alive in Rome where he was also baptised. As the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles writes:

‘[Cædwalla] went to Rome, and received baptism at the hands of Sergius the pope, who gave him the name of Peter; but in the course of seven nights afterwards, on the twelfth day before the calends of May, he died in his crisom-cloths, and was buried in the church of St. Peter.’

Ine 689 – c. 728

After the abdication of Cædwalla in 688, it is widely believed that Wessex descended into a period of internal strife and infighting between the various sub-kings. After several months a nobleman called Ine emerged victorious and secured the crown for himself, beginning 37 years of uninterrupted reign.

Ine inherited an extremely powerful kingdom stretching from the Severn Estuary through to the shorelines of Kent, although the eastern portions of the kingdom were notoriously rebellious and Ine struggled to maintain control of them. Instead, Ine turned his attention to the native Britons in Cornwall and Devon and managed to gain a large amount of territory to the west.

Ine is also known for his widescale reforms of Wessex which included an increased focus on trade, introducing coinage throughout the kingdom, as well as issuing a set of laws in 694. These laws covered a wide range of topics from damage caused by straying cattle to the rights of those convicted of murder, and are seen as an important milestone in the development of English society.

Interestingly, these laws also referred to the two types of people that lived in Wessex at the time. The Anglo-Saxons were known as the Englisc and lived mainly in the eastern portions of the kingdom, whilst the newly annexed territories in Devon were mainly populated by the native Britons.

Towards the end of his reign Ine became week and feeble and decided to abdicate in 728 in order to retire to Rome (at this time it was thought that a trip to Rome would aid one’s ascension to heaven).

Æthelheard c. 726 – 740

Thought to have been the brother-in-law of Ine, Æthelheard’s claim to the throne was contested by another nobleman called Oswald. The struggle for power lasted for around a year, and although Æthelheard eventually prevailed this was only through assistance from neighbouring Mercia.

For the next fourteen years, Æthelheard struggled to maintain his northern borders against the Mercians and lost a considerable amount of territory in the process. He also battled continuously against the growing hegemony of this northern neighbour, who after supporting him to the throne demanded that Wessex fall under their control.

Cuthred 740 – 756

Æthelheard was succeeded by his brother, Cuthred, who inherited the throne at the height of Mercian dominance. At this time, Wessex was seen as a puppet state of Mercia and for the first twelve years of Cuthred’s reign he helped them in numerous battles against the Welsh.

However, by 752 Cuthred was tired of Mercian overlordship and went to battle to regain independence for Wessex. To the surprise of everyone he won!

Sigeberht 756 – 757

Poor old Sigeberht! After succeeding Cuthred (thought to have been his cousin), he ruled for only a year before being stripped of the throne by a council of nobles for ‘unrighteous deeds’. Perhaps out of sympathy he was then given sub-king status over Hampshire, but after deciding to murder one of his own advisors he was subsequently exiled to the Forest of Andred and then killed in a revenge attack.

Cynewulf 757 – 786

Supported to the throne by Æthelbald of Mercia, Cynewulf may well have spent his first few months in power acting as a sub-king for the Mercians. However, when Æthelbald was assassinated later that year, Cynewulf saw an opportunity to assert an independent Wessex and even managed to expand his territory into the southern counties of Mercia.

Cynewulf was able to hold many of these Mercian territories until 779, when at the Battle of Bensington he was defeated by King Offa and forced to retreat back to his own lands. Cynewulf was eventually murdered in 786 by a nobleman that he had exiled many years earlier.

Beorhtric 786 – 802

Beorhtric, thought to have been a distant descendant of Cerdic (the founder of Wessex), had a rather eventful time as King. He succeeded to the throne with the backing of King Offa of Mercia, who no doubt saw his ascendancy as an opportunity to influence West Saxon politics. Beorhtric also married one of King Offa’s daughters, a lady called Eadburh, probably to gain further support from his more powerful neighbour to the north.

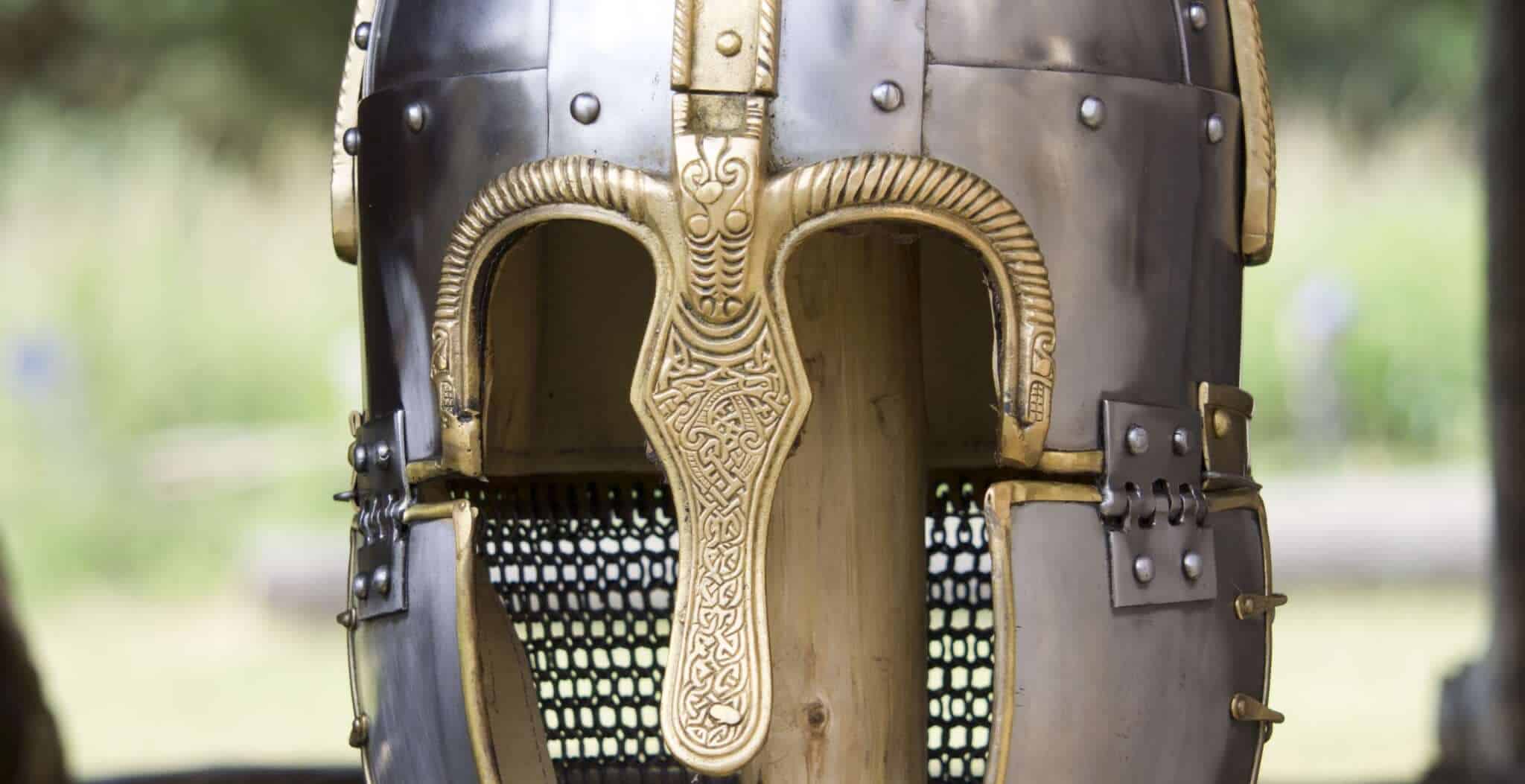

Beorhtric’s reign also saw the first Viking raids in England, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles writes:

AD787: ..and in his days came first three ships of the

Northmen from the land of robbers… These were the first

ships of the Danish men that sought the land of the English

nation.

If legend is to believed, Beorhtric died through accidental poisoning by none other than his wife, Eadburh. After being exiled to Germany for her crime, she was subsequently ‘hit on’ by Charlemagne with a rather peculiar chat up line. Apparently Charlemagne entered her chambers with his son and asked “Which do you prefer, me or my son, as a husband?”. Eadburh replied that due to his younger age she would prefer his son, to which Charlamagne famously said “Had you chosen me, you would have had both of us. But, since you chose him, you shall have neither.”

After this rather embarrassing affair, Eadburh decided to turn to nunnery and planned to live the rest of her life in a German convent. However, soon after taking her vows she was found having sex with another Saxon man and was duly expelled. Eadburh spent the rest of her days begging on the streets of a Pavia in northern Italy.

Egbert 802 – 839

One of the most famous of all the West Saxon kings, Egbert was actually exiled by his predecessor Beorhtric sometime in the 780s. Upon his death however, Egbert returned to Wessex, took the throne and reigned for the next 37 years.

One of the most famous of all the West Saxon kings, Egbert was actually exiled by his predecessor Beorhtric sometime in the 780s. Upon his death however, Egbert returned to Wessex, took the throne and reigned for the next 37 years.

Strangely, the first 20 or so years of his kingship are not very well documented although it is thought that he spent most of this time trying to keep Wessex independent from Mercia. This struggle for independence came to a head in 825 when the two sides met at the Battle of Ellandun near modern day Swindon.

Surprisingly, Egbert’s forces were victorious and the Mercians (led by Beornwulf) were forced to retreat back to the north. Riding high from his victory, Egbert sent his army south-east to annex Surrey, Sussex, Essex and Kent, all of which were under either direct or indirect Mercian control at the time. In the space of a year, the balance of power in Anglo-Saxon England had completely shifted and by 826 Wessex was seen as the most powerful kingdom in the country.

Egbert’s dominance of southern England continued for the next four years, with another major victory against Mercia in 829 which allowed him to completely annex the territory and claim all of southern Britain up to the River Humber. Egbert also was able to receive the submission of the Kingdom of Northumbria at the end of 829, leading the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles to call him ‘Ruler of Britain’ (although a more accurate title would have been ‘Ruler of England’ as both Wales and Scotland were still fiercely independent!).

Only one year after annexing Mercia for himself, the exiled King Wiglaf organised a revolt and drove the army of Wessex back into their own territory. However, the Mercians never reclaimed their lost territories of Kent, Sussex and Surrey and Wessex was still to be considered the most powerful kingdom in southern England.

When Egbert died in 839 he was succeeded by his only son, Æthelwulf.

Æthelwulf, 839 – 858

Æthelwulf was already the king of Kent before his ascension to the throne of Wessex, a title awarded to him by his father in 825. Keeping to this family tradition, when Egbert died in 839 Æthelwulf subsequently handed Kent to his own son, Æthelstan, to rule it on his behalf.

Æthelwulf was already the king of Kent before his ascension to the throne of Wessex, a title awarded to him by his father in 825. Keeping to this family tradition, when Egbert died in 839 Æthelwulf subsequently handed Kent to his own son, Æthelstan, to rule it on his behalf.

Not much is known about Æthelwulf’s reign except that he an extremely religious man, prone to the occasional gaffe, and rather unambitious, although he did fairly well at keeping the invading Vikings at bay (namely at Carhampton and Ockley in Surrey, the latter of which was said to have been ‘ the greatest slaughter of heathen host ever made’.) Æthelwulf was also said to have been rather fond of his wife, Osburh, and together they bore six children (five sons and a daughter).

In 853 Æthelwulf sent his youngest son, Alfred (later to become King Alfred the Great) to Rome on a pilgrimage. However after the death of his wife in 855, Æthelwulf decided to join him in Italy and on his return the following year met his second wife, a 12 year old girl called Judith, a French princess.

Quite to his surprise, when Æthelwulf finally returned to British shores in 856 he found that his oldest surviving son, Æthelbald, had stolen the kingdom from him! Although Æthelwulf had more than enough support of the sub-kings to reclaim the throne, his Christian charity led him to cede the western half of Wessex to Æthelbald in an attempt to keep the kingdom from breaking out into civil war.

When Æthelwulf died in 858 the throne of Wessex unsurprisingly fell to Æthelbald.

Æthelbald 858 – 860

Little is known about Æthelbald’s short reign except that he married his father’s widow, Judith, who at the time was only 14! Æthelbald died ages 27 at Sherborne in Dorset from an unknown ailment or disease.

After Æthelbald’s death in 860, Judith went on to marry for a third time! The drawing above shows her riding alongside her third husband, Baldwin of Flanders.

Æthelberht 860 – 865

Æthelberht, brother of Æthelbald and third eldest son of Æthelwulf, succeeded to the throne of Wessex after his brother died without having fathered any children. His first order of business was to integrate the Kingdom of Kent into Wessex, whereas previously it had been merely a satellite state.

Æthelberht is said to have presided over a time of relative peace, with the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms too preoccupied with Viking invasions to worry about domestic rivalries. Wessex was not immune from these Viking incursions either, and during his reign Æthelberht saw off the Danish invaders from a failed storming of Winchester as well as repeated incursions to the eastern coast of Kent.

Like his brother before him, Æthelberht died childless and the throne was passed to his brother, Æthelred.

Æthelred 865 – 871

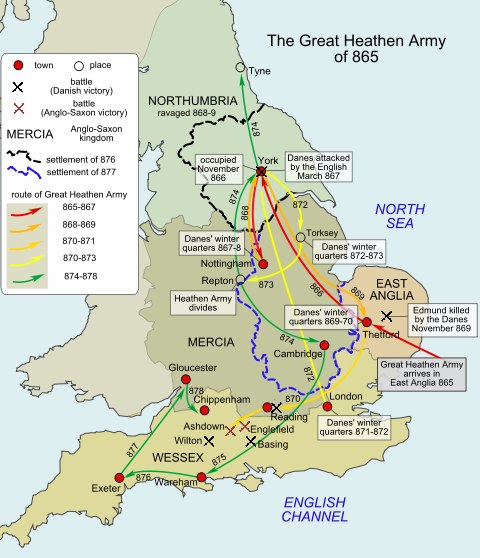

Æthelred’s six years as King of Wessex began with a great Viking army storming the east of England. This ‘Great Heathen Army’ quickly overran the independent Kingdom of East Anglia and had soon defeated the mighty Kingdom of Northumbria. With the Vikings turning their sights southwards, Burgred King of Mercia appealed to Æthelred for assistance and he subsequently sent an army to meet the Vikings near Nottingham. Unfortunately this was to be a wasted trip as the Vikings never showed up, and Burgred was instead forced to ‘buy off’ the Danish horde to avoid them invading his lands.

Æthelred’s six years as King of Wessex began with a great Viking army storming the east of England. This ‘Great Heathen Army’ quickly overran the independent Kingdom of East Anglia and had soon defeated the mighty Kingdom of Northumbria. With the Vikings turning their sights southwards, Burgred King of Mercia appealed to Æthelred for assistance and he subsequently sent an army to meet the Vikings near Nottingham. Unfortunately this was to be a wasted trip as the Vikings never showed up, and Burgred was instead forced to ‘buy off’ the Danish horde to avoid them invading his lands.

With Northumbria and East Anglia now under Viking control, by the winter of 870 the Great Heathen Army turned their sights on Wessex. January, February and March of 871 saw Wessex engage the Vikings on four separate occasions, winning just one of them.

Alfred the Great 871 – 899

The only English monarch to have ever been bestowed the title of ‘Great’, Alfred is widely acknowledged as one of the most important leaders in English history.

Before King Æthelred died in 871, he signed an agreement with Alfred (his younger brother) which stated that when he died the throne would not pass to his eldest son. Instead, due the increasing Viking threat from the north, the throne would pass to Alfred who was a much more experienced and mature military leader.

The first of King Alfred’s battles against the Danes was in May 871 in Wilton, Wiltshire. This was to be a catastrophic defeat for Wessex, and as a consequence Alfred was forced to make peace with (or more likely buy off) the Vikings in order to prevent them from taking control of the Kingdom.

ADVERTISEMENT

For the next five years there was to be an uneasy peace between Wessex and the Danish, with the Viking horde setting up base in Mercian London and focusing their attention on other parts of England. This peace remained in place until a new Danish leader, Guthrum, came to power in 876 and launched a surprise attack on Wareham in Dorset. For the next year and a half, the Danish tried unsuccessfully to take Wessex, but in January 878 their fortunes were to change as a surprise attack on Chippenham pushed Alfred and the Wessex army back into a small corner of the Somerset Levels.

Defeated, short on troops and with morale at an all time low, Alfred and his remaining forces hid from the enemy forces in a small town in the marshes called Athelney. From here, Alfred started sending out messengers and scouts to rally local militia from Somerset, Devon, Wiltshire and Dorset.

By May 878 Alfred had gathered enough reinforcements to launch a counter offensive against the Danes, and on the 10th May (give or take a few days!) he defeated them at the Battle of Edington. Riding high from victory, Alfred continued with his army northwards to Chippenham and defeated the Danish stronghold by starving them into submission. As part of the terms for surrender, Alfred demanded that Wulfred convert to Christianity and two weeks later the baptism took place at a town called Wedmore in Somerset. This surrender is consequently known as ‘The Peace of Wedmore’.

The Peace of Wedmore led to a period of relative peace in England, with the south and west of England being ceded to the Anglo-Saxons and the north and east to the Danish (creating a kingdom known as Danelaw). However, this was to be an uneasy peace and Alfred was determined not to risk his kingdon again. He subsequently embarked on a modernisation of his military, focused around a ‘Burgal system’. This policy was to ensure that no place in Anglo-Saxon England would be more than 20 miles from a fortified town, allowing reinforcements to flow easily throughout the kingdom. Alfred also ordered the construction of a new, larger and much improved navy to counter Danish seapower.

Alfred also embarked on a series of academic reforms, and recruited the most prestigious scholars from the British Isles to set up a court school for noble-born children as well as ‘intellectually promising boys of lesser birth’. He also made literacy a requirement for anyone in government, as well as ordering the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles to be written.

When King Guthrum died in 890, a power-vacuum opened up in Danelaw and a set of fueding sub-kings started fighting over power. This was to mark the beginning of another six years of Danish attacks on the Anglo-Saxons, although with Alfred’s newly improved defenses these attacks were almost entirely repelled. Things came to a head in 897, when after a series of failed raiding attempts the Danish army effectively disbanded, with some retiring to Danelaw and some retreating back to mainland Europe.

Alfred died a few years later in 899 having secured the future of Anglo-Saxon England.

Edward the Elder 899 – 924

In 899 the throne of Wessex fell to Alfred’s eldest son, Edward, although this was disputed by one of Edward’s cousins called Æthelwold. Determined to expel Edward from power, Æthelwold sought the help of the Danes to the east and by 902 his army (along with Viking help) had attacked Mercia and had reached the Wiltshire borders. In retaliation Edward successfully attacked the Danish kingdom of East Anglia but then, on ordering his troops back to Wessex, some of them refused and continued northwards (probably for more loot!). This culminated in the Battle of the Holme, where the East Anglian Danes met the stragglers of the Wessex army and subsequently defeated them. However, the Danes also suffered some heavy losses during the battle and both the king of East Anglia and Æthelwold, pretender to the Wessex throne, lost their lives.

In 899 the throne of Wessex fell to Alfred’s eldest son, Edward, although this was disputed by one of Edward’s cousins called Æthelwold. Determined to expel Edward from power, Æthelwold sought the help of the Danes to the east and by 902 his army (along with Viking help) had attacked Mercia and had reached the Wiltshire borders. In retaliation Edward successfully attacked the Danish kingdom of East Anglia but then, on ordering his troops back to Wessex, some of them refused and continued northwards (probably for more loot!). This culminated in the Battle of the Holme, where the East Anglian Danes met the stragglers of the Wessex army and subsequently defeated them. However, the Danes also suffered some heavy losses during the battle and both the king of East Anglia and Æthelwold, pretender to the Wessex throne, lost their lives.

After the Battle of the Holme, Edward the Elder spent the rest of his years in almost constant clashes with the Danes to the north and east. With the help of the Mercian army (who had long been under the indirect control of Wessex), Edward was even able to defeat the Danish in East Anglia, leaving them with only the kingdom of Northumbria. On the death of Edward’s sister, Æthelflæd of Mercia in 918, Edward also brought the Kingdom of Mercia under the direct control of Wessex and from this point on, Wessex was the only kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons. By the end of his reign in 924, Edward had almost completely removed any threat of Viking invasion, and even the Scots, Danes and Welsh all referred to him as ‘Father and lord’.

by the king of the Scots, and by the Scots, and King Reginald,

and by all the North-humbrians, and also the king of the

Strath-clyde Britons, and by all the Strath-clyde Britons.”

Ælfweard July – August 924

Reigning only for around 4 weeks and probably never crowned, all we know about Ælfweard is a single sentence from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles:

This year died King Edward at Farndon in Mercia; and

Ælfweard his son died very soon after this, in Oxford. Their

bodies lie at Winchester.

Æthelstan August 924 – 27th October 939

Æthelstan, the first ever King of England, took the Wessex throne in 924 after his elder brother’s death. However, although he was very popular in Mercia, Æthelstan was less well liked in Wessex as he had been raised and schooled outside of the kingdom. This meant that for the first year of his reign he had to rally the support of the sub-kings of Wessex, including one particularly vocal opposition leader called Alfred. Although he succeed in doing this, it meant that he was not crowned until the 4th September 925. Interesting, the coronation was held in Kingston upon Thames on the historic border between Mercia and Wessex.

By the time of his coronation in 925 the Anglo-Saxons had retaken much of England leaving only southern Northumbria (centered around the capital of York) in the hands of the Danish. This small corner of the old Danelaw had a truce with the Anglo-Saxons which prevented them from going to war with each other, but when the Danish king Sihtric died in 927, Æthelstan saw an opportunity to take this final vestige of Danish territory.

The campaign was swift, and within a few months Æthelstan had taken control of York and received the submission of the Danish. He then called for a gathering of kings from throughout Britain, including those from Wales and Scotland, to accept his overlordship and acknowledge him as King of England. Wary of the power that a united England would have, the Welsh and Scottish agreed under the proviso that fixed borders should be put in place between the lands.

For the next seven years there was relative peace throughout Britain until in 934 Æthelstan decided to invade Scotland. There is still a great deal of uncertainly over why he decided to do this, but what is known is that Æthelstan was supported by the Kings of Wales and that his invading army reached as far as Orkney. It is thought that the campaign was relatively successful, and that as a consequence both King Constantine of Scotland and Owain of Strathclyde accepted Æthelstan’s overlordship.

This overlordship lasted for two years until in 937 when both Owain and Constantine, along with the Danish king Guthfrith of Dublin, marched against Æthelstan’s army in an attempt to invade England. This was to be one of the greatest battles in British history: The Battle of Brunanburh (follow the link for our full article about the battle).

By the time of Æthelstan’s death in 939 he had defeated the Vikings, united the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England under a single banner, and had repeatedly forced both the Welsh and Scottish kings to accept his overlordship of Britain. Æthelstan was therefore the last king of Wessex and the first king of England.